Citizen Scientists Jump Aboard NASA's Jupiter Mission to Create Amazing Images

A camera flying aboard NASA's current mission to Jupiter is snapping stunning new images of the gas giant's stormy surface, and enabling members of the public to take an active role in this historic mission.

The Juno probe is flying closer to Jupiter than any spacecraft has done in history, coming to within about 3,100 miles (5,000 kilometers) of the giant's stormy cloud tops. Its primary science mission is to gather information about the planet's interior — peering through its thick cloud layers and all the way down to its rocky core.

The JunoCam instrument is an exception: It takes pictures of the surface of Jupiter's cloud tops. Its mission is primarily to serve as an outreach tool: The data that is sent back to Earth is made available to the public, and "citizen scientists" are welcome to process the images and try to learn from them. Looking ahead, members of the public will be able to vote on which features JunoCam should eye next. [Jupiter Shines in Scientific and Artistic Images by Citizen Scientists (Gallery)]

The creators of the JunoCam outreach program wanted to "involve the public in every aspect of what an imaging team would ordinarily be doing," according to Candy Hansen, a Juno co-investigator and head of the JunoCam team. Hansen discussed the project during a press briefing at the 2016 meeting of the American Astronomical Society Division for Planetary Sciences (AAS DPS) in Pasadena, California.

People who participate in JunoCam get to see what scientists go through during a mission — "the good days and the more challenging days, and to sort of live our lives with us," Hansen said. The goal is to allow the public to join the mission "in a participatory way, not a passive way."

Juno arrived at the Jupiter system in August, and its orbit is highly elongated, so that it comes very close to Jupiter (for only a matter of hours), and then swings far out into space. This path allows the probe to loop in between the planet's cloud tops and a ring of very intense radiation that wraps around Jupiter, which could easily destroy the electronics on board. Such a path also brings Juno closer to Jupiter than any probe in history. Juno is currently on a 53-day orbit, but it may still drop down to a 14-day orbit.

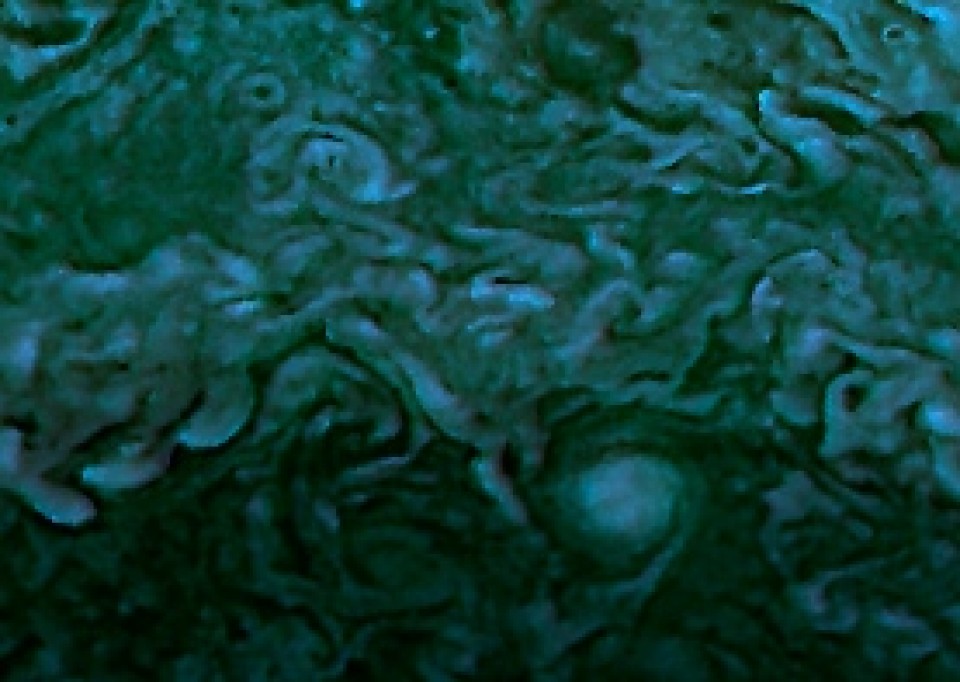

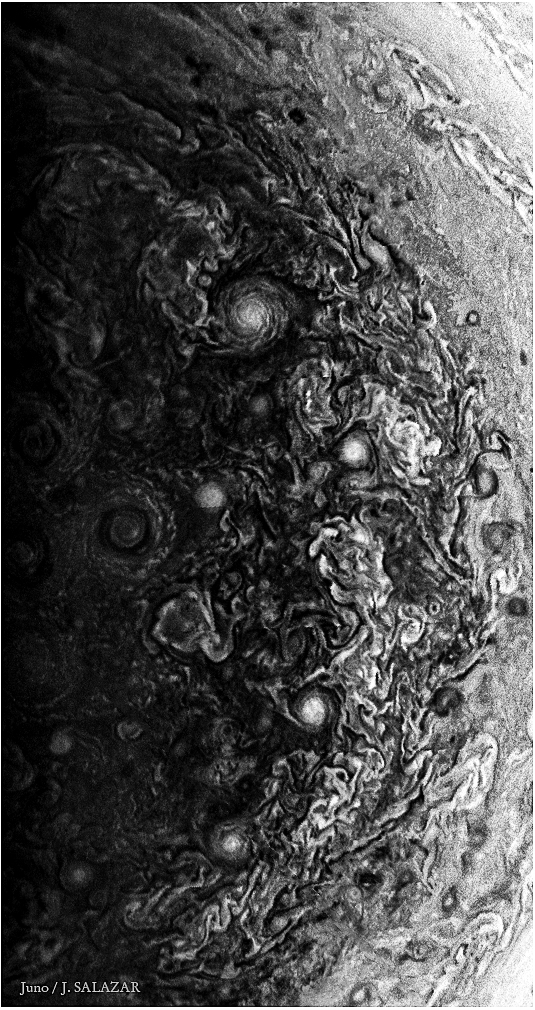

So far, JunoCam has only sent one batch of data back to Earth (since Juno has only made one close flyby with its instruments turned on). The JunoCam team posted "raw images" to the JunoCam website, and already public participants have used them to post dozens of processed images to the website. Some of the images have been processed to make it easier to see storms and physical features in Jupiter's clouds; others have been processed to create visually engaging works of art.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Citizen scientists

On the JunoCam website, people can submit processed images, and then discuss their results and techniques in the discussion section. Or, if the participants aren't processing images, they can just ask questions of the people doing the processing.

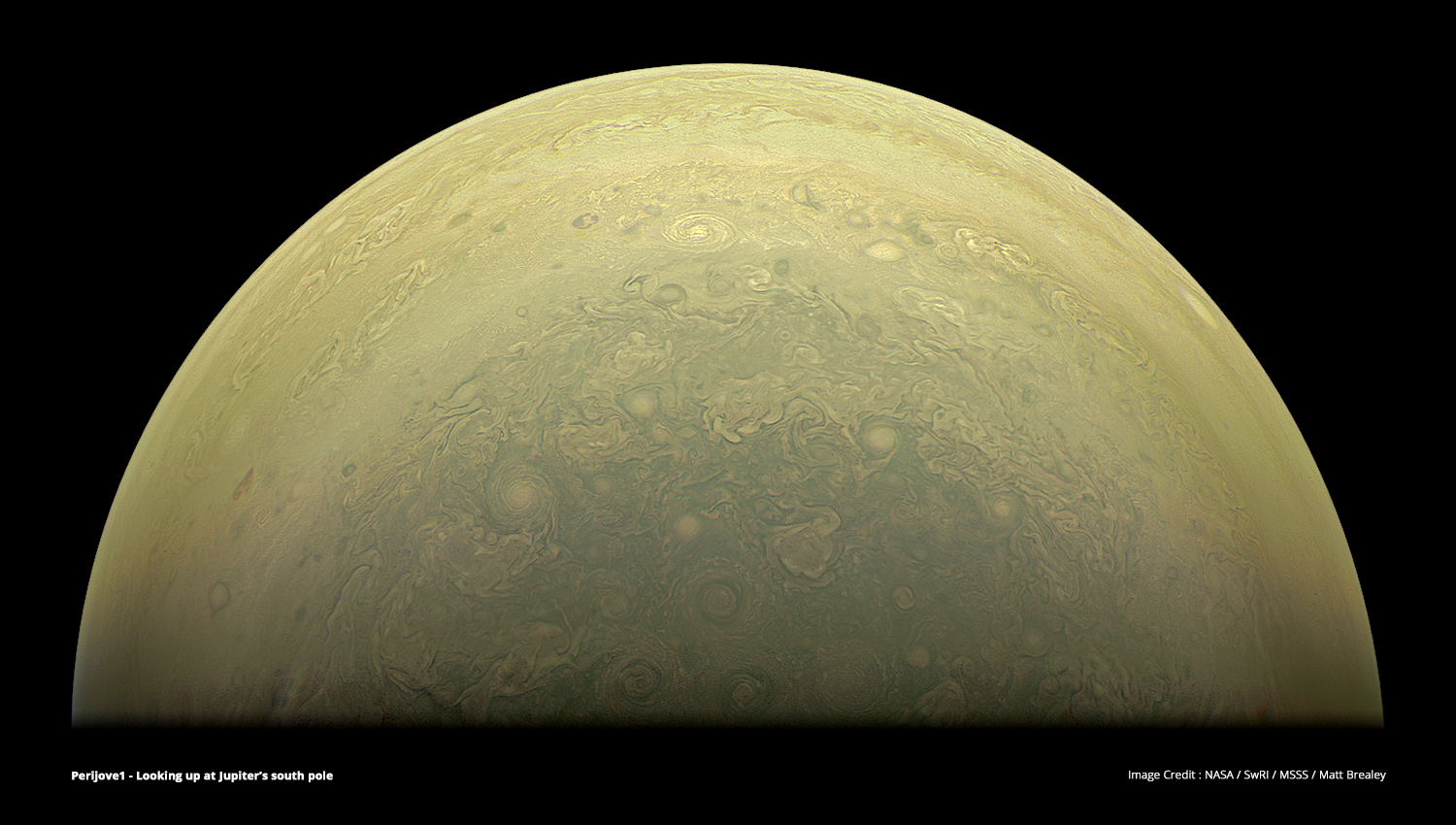

JunoCam participant Matt Brealey told Space.com that he has been "attempting to use software from the Visual Effects industry" to process the images from JunoCam. (You can see examples of his work here and here, and you can read an article he wrote about his technique here).

"I've been fascinated by space imagery for as long as I can remember, so suddenly realizing that I could in some small way be a part of creating new images was extremely exciting," Brealey told Space.com via email. "That combined with the technical challenge of using tools from the VFX industry really [piqued] my interest in the project."

The skill level among the participants varies, according to Gerald Eichstädt, a software programmer who has been processing images from JunoCam with software he wrote especially for this project (which puts him at the upper end of the skill-level spectrum). He told Space.com that many people are using commercially available software, including some that's provided on the JunoCam website.

"JunoCam images provide challenges on almost any level; you can improve your skills according to your individual capabilities," he wrote. "To squeeze out as much as possible from the JunoCam images, you need more than (technical) skills; you also need to apply your skills, either by using existing software in an appropriate way, or by developing and applying appropriate software. But there are also many things you can do with consumer software. Good creative ideas are another important factor and may well be able to compensate [for] less technical skills."

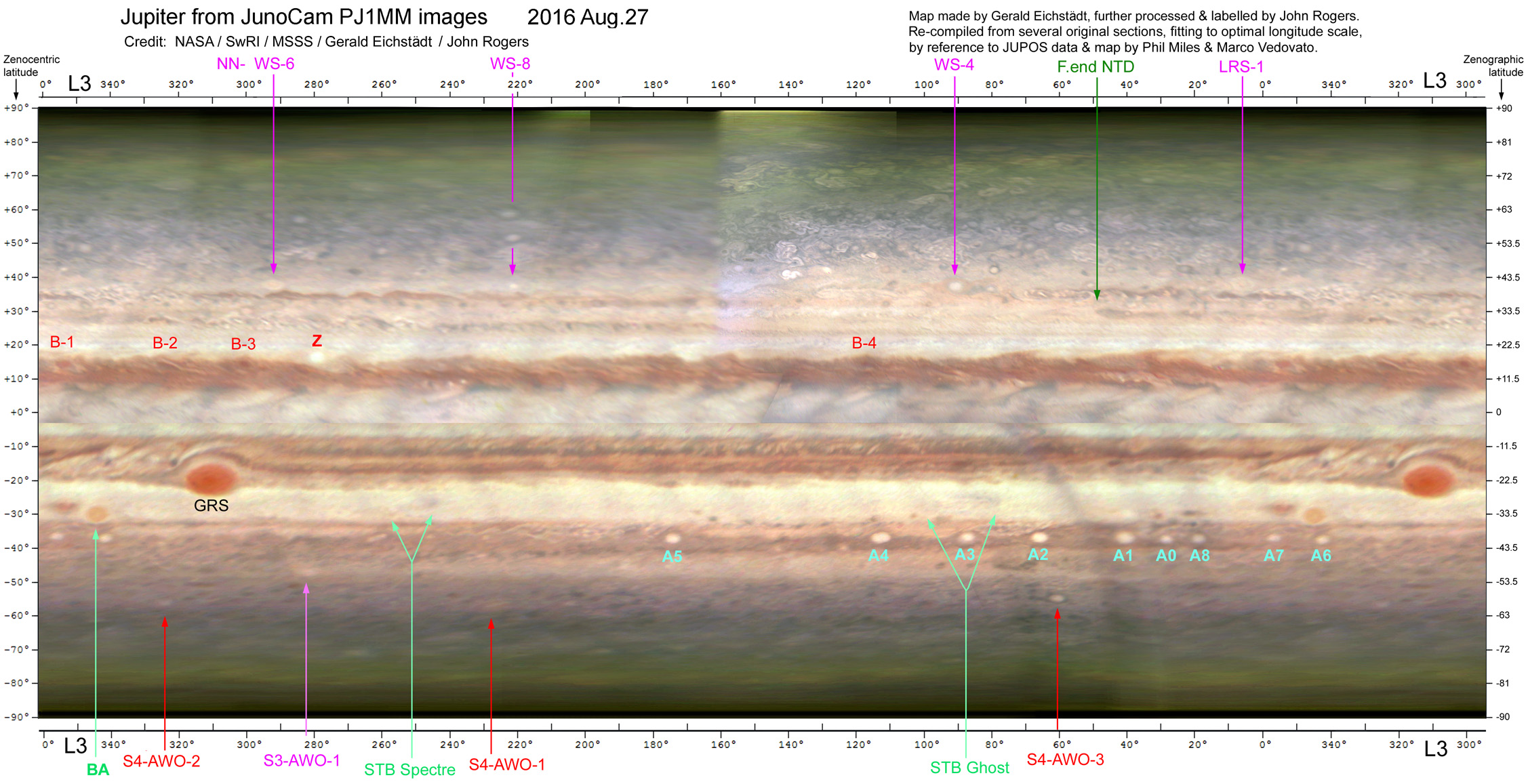

Eichstädt said that he has been working with people who have skills that are different from his own (such as extensive knowledge about Jupiter's surface features), and he has been working with them to get more out of the images he makes. He said he has processed thousands of images and has posted most of them to his own website to avoid flooding the JunoCam website.

Participants can post their processed images to the mission website for others to see — Hansen said she definitely wants people to share the images, not just "post them to their private Facebook page." The goal of some of the processing is to analyze the different features that the instrument sees on the surface, while other images are processed with the aim of creating amazing aesthetic value. Some images accomplish both of those things.

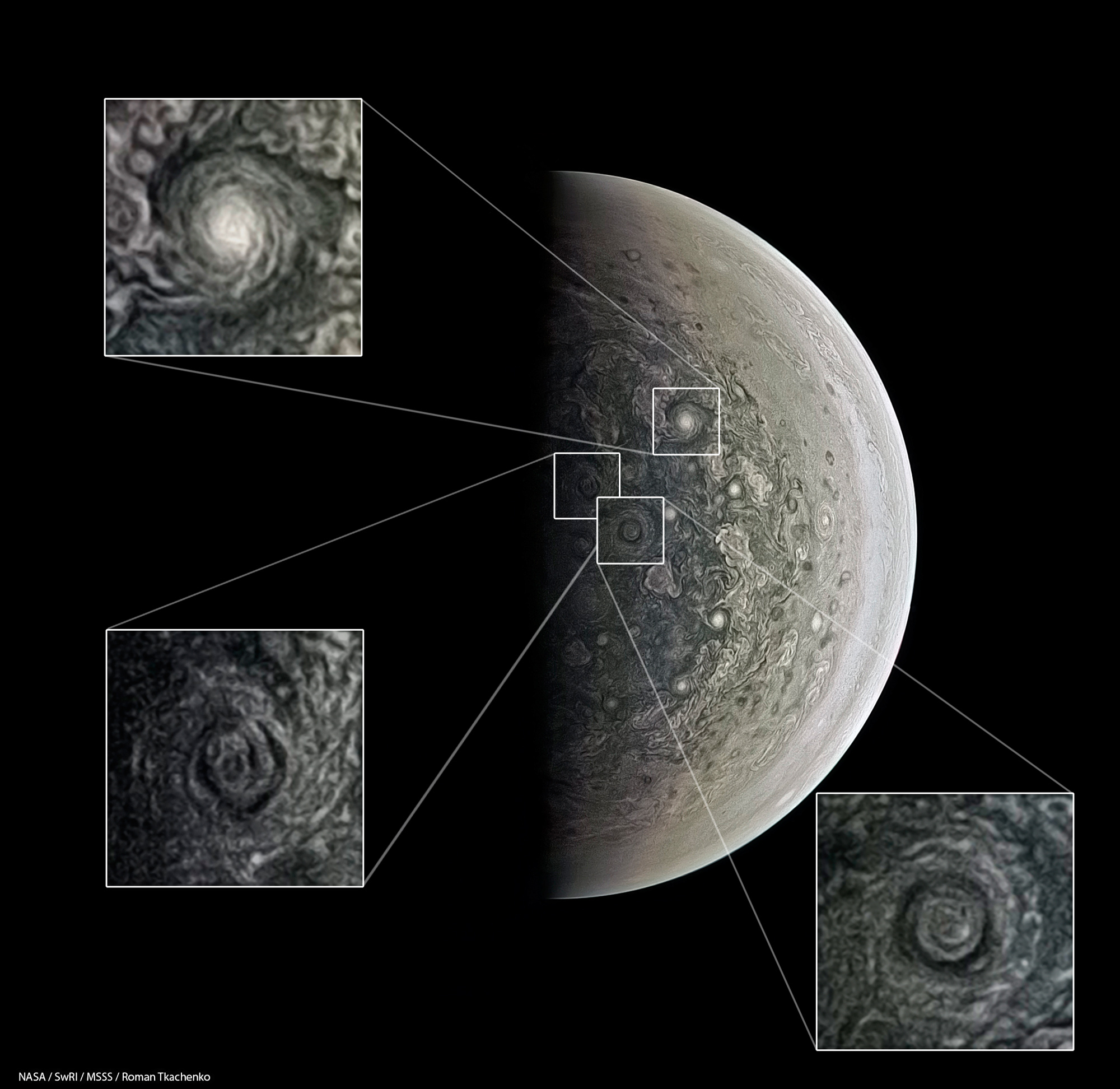

"It's pretty cool that a lot of processed images are collected in one place and people can discuss them," Roman Tkachenko, a citizen scientist who is processing JunoCam images, told Space.com. Tkachenko's images focus on identifying swirling storms and other prominent features in the atmosphere. "Many amateur image processors face the problem of having no opportunity to show their work to the public, because their audience on social media is too small. This project partially solved that problem, at least regarding images taken by Juno spacecraft."

While the JunoCam instrument is not part of the probe's suite of science instruments, its first snapshots of Jupiter revealed never-before-seen features of the Jovian giant, including clusters of storms near the planet's north pole, and a cyclone stretching 52 miles (85 km) above the base surface level, according to Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator. Bolton discussed the early results during the same press briefing at the 2016 AAS DPS meeting.

"I've not the funding to do a space mission myself, so I can save a lot of time and money by joining an existing mission funded mostly by the U.S. taxpayers," Eichstädt wrote. "Processing JunoCam images is very challenging for most people, and I knew that I would be able to do it; so it's to some degree an honor and a duty to give the U.S. taxpayers something back."

A leap of faith

Besides image processing and the discussion board, the JunoCam project has two other key features. First, the JunoCam team is asking amateur astronomers to post telescopic images of Jupiter and other data that is gathered from Earth. Those uploads are then used to help Juno team members plan what JunoCam will image during upcoming flybys of Jupiter. Some of the images that have been processed are using that data already: Some of the user-submitted image show how the features that are seen in the JunoCam image correlate with the features that are seen in images of Jupiter taken by previous space or ground-based instruments.

"That allows us to connect what we're seeing from our different perspective to the historical record of the dynamics of Jupiter's atmosphere," Hansen said.

The final task that the JunoCam project will pose to the public is voting on which features will be imaged during future flybys. JunoCam can't take pictures continuously while Juno is making its close flyby of Jupiter, so the organizers have to be selective. Hansen said there will be a "partial vote" for what JunoCam should focus on during its next close approach on Dec. 11. Full voting will take place for the following close approach, scheduled to take place on Feb. 2.

"We took a real leap of faith with this experiment with the public — that people would actually think this is cool and participate," Hanse said. "And I'm really so pleased with the response that we've gotten. I really feel like our leap of faith was justified."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter