This Is the Best View Yet of Europe's Mars Lander Crash Site

Europe's ExoMars lander gouged out a crater 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) deep and nearly 8 feet (2.4 m) wide when it crashed into the Red Planet's surface last week, a new photo by a NASA Mars orbiter reveals.

The lander, known as Schiaparelli, apparently deployed its parachute prematurely and didn't fire its thrusters nearly long enough to pull off a soft landing as planned on Oct. 19, European Space Agency (ESA) officials have said.

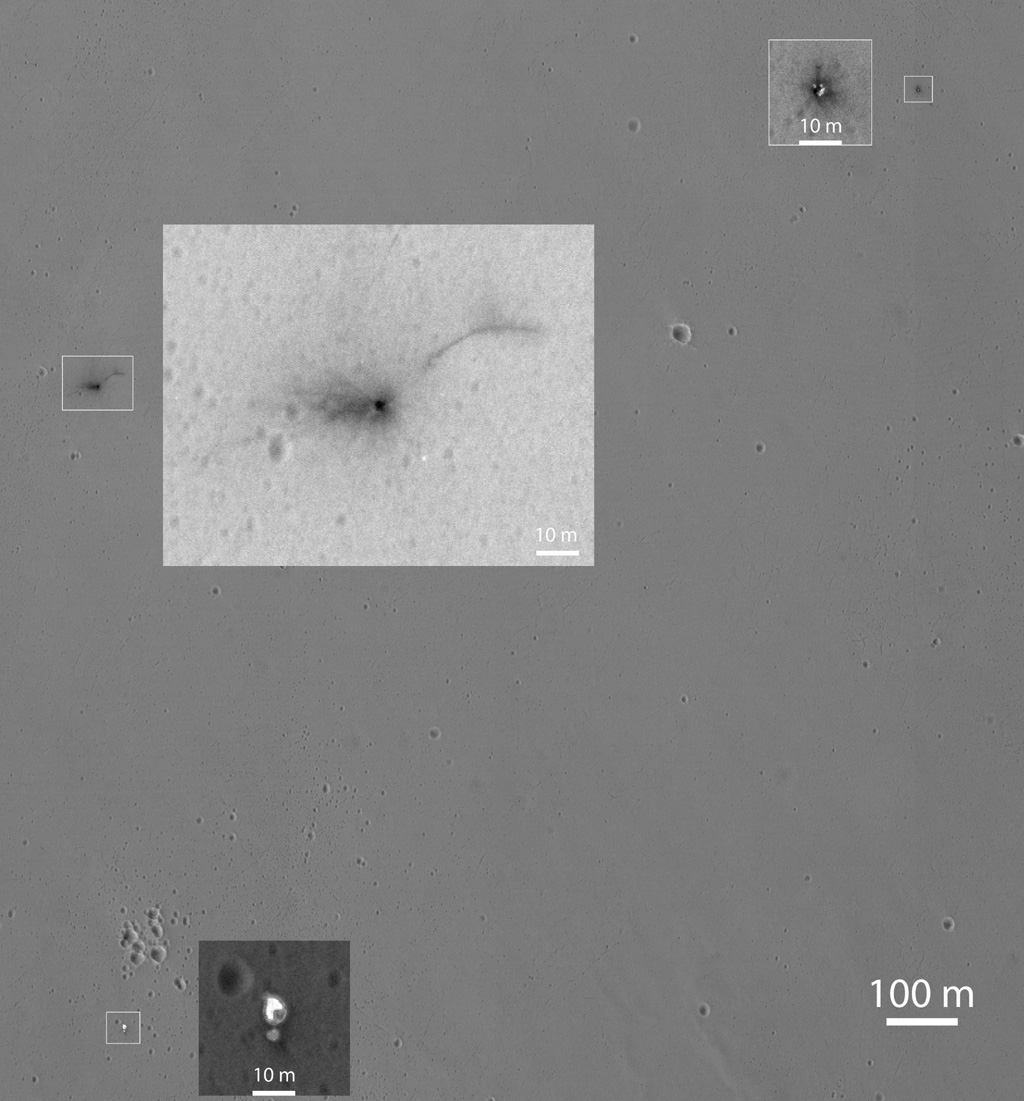

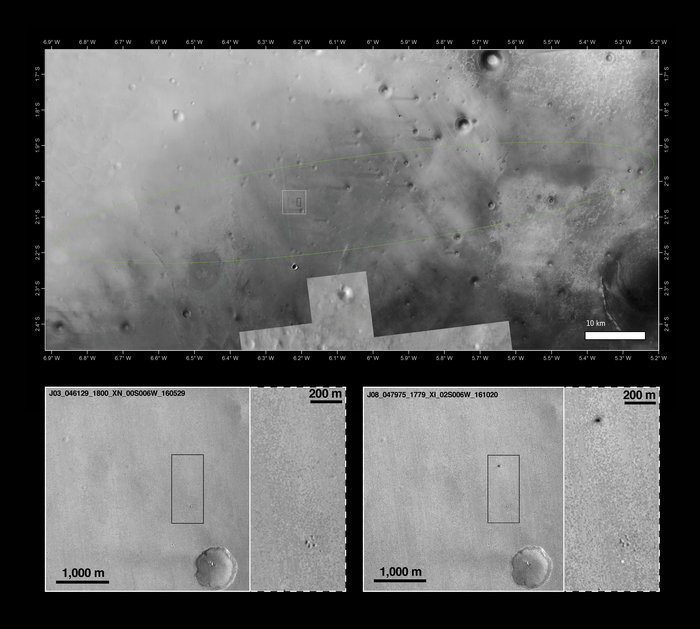

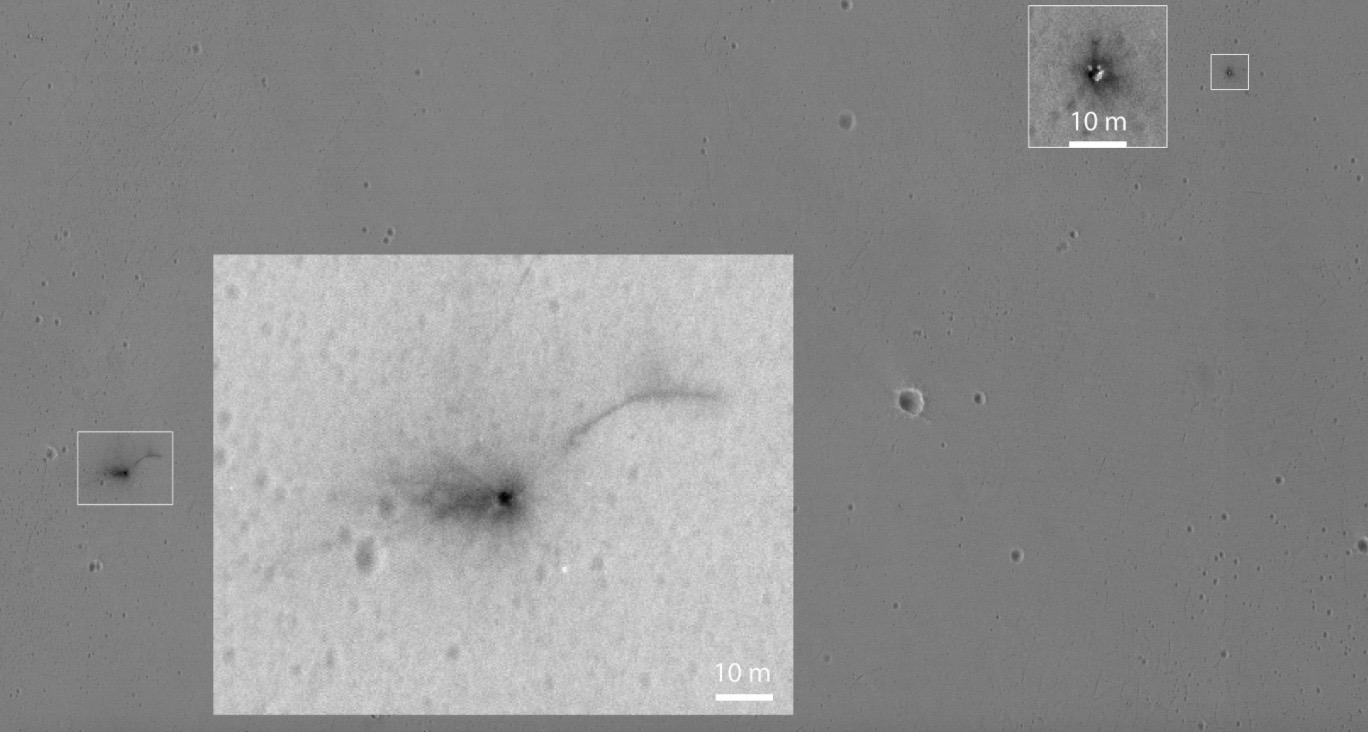

The new image, which was captured by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) on Tuesday (Oct. 25), shows the aftermath of Schiaparelli's violent impact. [In Photos: Europe's Schiaparelli Mars Landing Day]

First of all, there's the main crater, which the lander blasted out when it hit the surface at a speed of about 180 mph (300 km/h). The fuzzy dark smudges around the central crater are difficult to interpret at the moment, ESA officials said: These markings are asymmetrical, which suggests that the impactor was traveling at a low angle to the ground, but Schiaparelli should have been descending pretty much perpendicular to the surface when it hit.

"It is possible the hydrazine propellant tanks in the module exploded preferentially in one direction upon impact, throwing debris from the planet’s surface in the direction of the blast, but more analysis is needed to explore this idea further," ESA officials wrote in an update today (Oct. 27).

"An additional long, dark arc is seen to the upper right of the dark patch but is currently unexplained," they added. "It may also be linked to the impact and possible explosion."

About 0.9 miles (1.4 kilometers) south of this crater is a bright feature above a smaller gray disk, which are almost certainly Schiaparelli's 39-foot-wide (12 m) parachute and its attached rear heat shield, respectively, ESA officials said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Another bright feature 0.9 miles (1.4 km) east of the Schiaparelli crater is probably the lander's front heat shield, they added.

"The mottled bright and dark appearance of this feature is interpreted as reflections from the multilayered thermal insulation that covers the inside of the front heatshield. Further imaging from different angles should be able to confirm this interpretation," ESA officials wrote in the update. "The dark features around the front heatshield are likely from surface dust disturbed during impact."

Schiaparelli launched in March 2016 along with the Trace Gas Orbiter. Together, the two spacecraft make up the ExoMars 2016 mission — the first part of the two-phase ExoMars program, which ESA leads with assistance from its chief partner, the Russian federal space agency Roscosmos.

The second phase of ExoMars aims to land a life-hunting rover on the Red Planet's surface in 2021. Schiaparelli's main goal was to test out the technologies needed to get this rover down safely, and the data gathered during the lander's Oct. 19 descent should be helpful in this regard, ESA officials have said.

The ExoMars team expects to wrap up its investigation into what exactly happened during Schiaparelli's descent by mid-November, ESA officials added.

TGO, for its part, aced a crucial orbit-insertion burn on Oct. 19 and is in good shape as it loops around Mars on a highly elliptical, four-day-long orbit, mission team members said. Early next year, the spacecraft will begin moving into its final science orbit, a circular path with an altitude of 250 miles (400 km).

TGO should reach that orbit by March 2018, at which point the spacecraft will begin hunting for buried water ice and sniffing the Martian atmosphere for methane and other gases that could be signs of life. This science mission will last for about two years. TGO will also serve as a communications relay for the ExoMars rover and other surface craft before ending operations in 2022.

MRO took the new photo with its supersharp High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera. The Schiaparelli crash site was first identified last week in images captured by MRO's lower-resolution CTX camera.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.