Author Q&A: Margot Lee Shetterly Reveals NASA's 'Hidden Figures'

More than a half century after the first NASA astronauts launched into space, one might think that there are no sweeping narratives left untold about the early years of the U.S. space program.

But there was at least one history remaining to be written: that of the women, and in particular the African-American women, who worked as the "human computers" at NASA's original research laboratory and provided the calculations necessary for sending American spacecraft and astronauts into space and to the moon.

It is not that the women of West Computing at the Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, were more crucial than their white woman counterparts in East Computing, or even the largely white and almost entirely male engineers who both divisions of women mathematicians supported at Langley. Nor were they more important to the program's early success than the teams who staffed Mission Control or, for that matter, the astronauts rode their work into orbit. The women, themselves, would be the first to ensure that was clear. [On 'Hidden Figures' Movie Set, NASA's Early Years Take Center Stage]

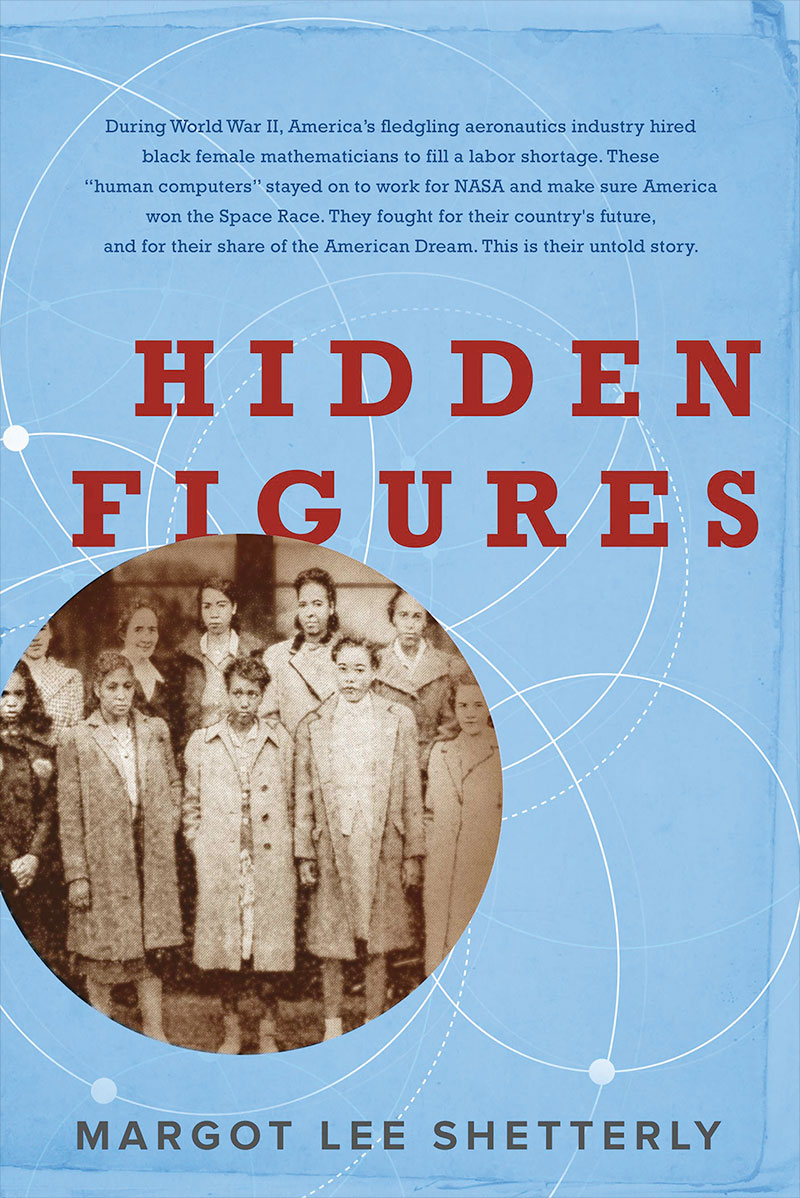

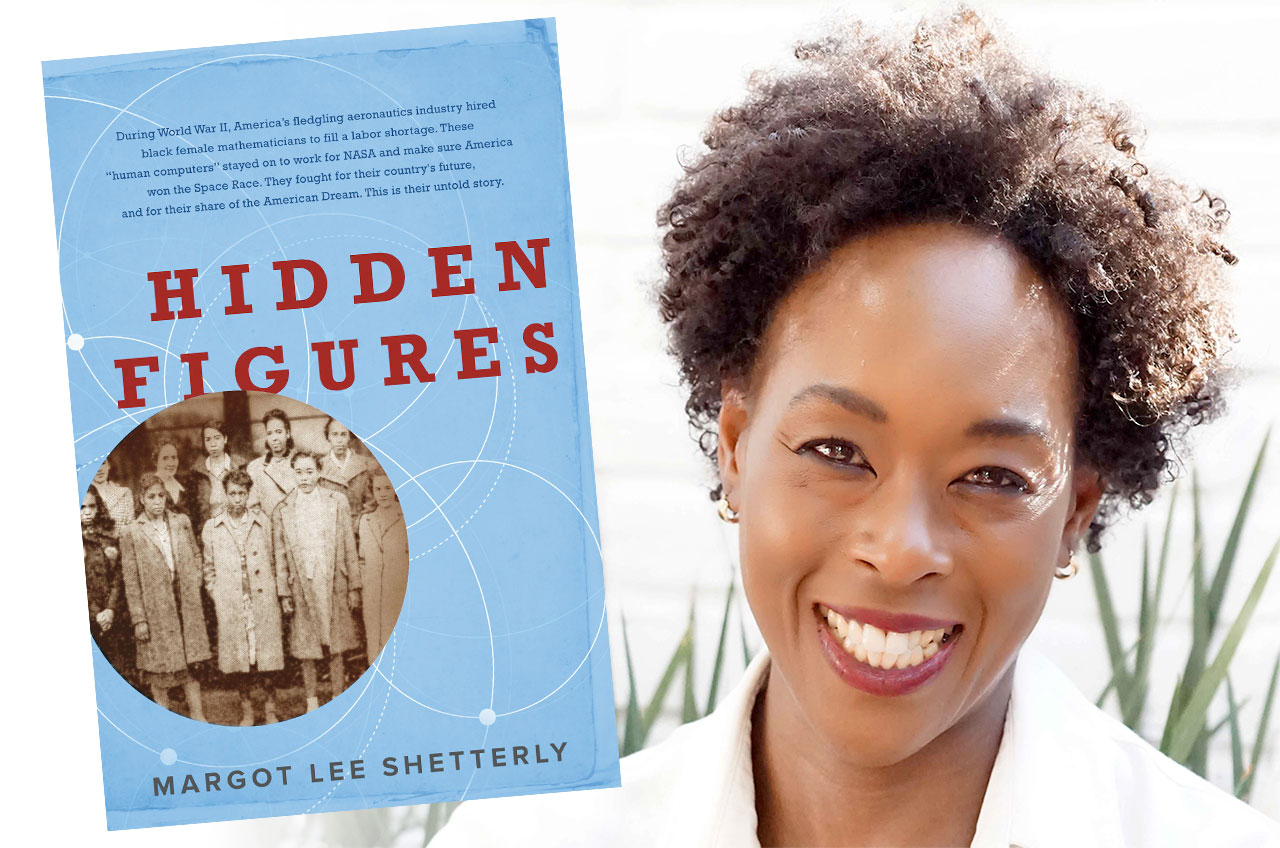

Rather it's their story, now documented within the pages of journalist and researcher Margot Lee Shetterly's "Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race" (William Morrow), that helps re-integrate the history of the women's rights and civil rights movements within the history of the space program.

These women, including Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson and Katherine Johnson, were hidden from that history until recently. Or, as Shetterly writes in the book, not hidden but waiting to be found.

"The title of this book is something of a misnomer. The history that has come together in these pages wasn't so much hidden as unseen — fragments patiently biding their time in footnotes and family anecdotes and musty folders before returning to view," she explains.

And now that history is not just being revealed in the book. Adapted for film even before Shetterly finished her writing, 20th Century Fox is set to release "Hidden Figures" as a movie in January, starring actors Taraji P. Henson, Octavia Spencer, Janelle Monae, Kevin Costner and Kirsten Dunst. ['Hidden Figures' Tells Story Of 3 African-American Women At NASA During Space Race (Video)]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

collectSPACE.com recently spoke with Shetterly about how she came to author "Hidden Figures" and why it was an untold history until now.

collectSPACE: Though there have been books before that have discussed the space race within the larger context of the years when it occurred, few have focused in any detail how the civil rights and women's rights movements were as much of a factor at NASA as they were for the nation as a whole. What led you to recognizing this story and why do you think it has gone largely untold until now?

Margot Lee Shetterly: I think it was because those things connect, but not in obvious ways — it just so happens they connect to my life.

All of those stories directly pertain to my background and history and so in a way, writing about those was a way of me exploring how I came about. I grew up in Hampton, my dad worked at NASA, there were tons of people around who worked at NASA and there was the African-American history.

And I think another part of it was that we tend to put these histories in silos. Sometimes you will read a story about women and it's "women's history." You'll read a story about African Americans and it's "African-American history." You will read a story about space and it is "space history." And all of those things are American history. There is no reason for us to isolate them and see them as separate when they are all part of the same thing.

The way I see it, and the way I hope people will see this book and the movie, is that this is "capital 'H'" history that happens to be told through the eyes of these protagonists who are African American women. Or you could say this is "capital H" history that happens to be told through the eyes of a bunch of mathematicians. This is History that happens to be told from the point of view of people who became a space program. But it is all capital 'H' American History.

collectSPACE: There are people who worked at NASA at the time who today say they were unaware of the women, or at least were unaware of how many of them there were. Did you run into this during your research? Were there any communities who knew of the women already?

Shetterly: In Hampton, where I grew up, so many people knew about this story, knew about these women — black women, white women, women. They knew because it was like, "Oh! My grandma used to work at NASA" or "My mom worked at NASA" or "The lady at church worked at NASA."

So they knew about the story but most of them were like me, it was just normal. As a kid I'd think, "My dad works at NASA, he's a research scientist. Great, everybody's got a job, and that's what they do." Normal!

There were people in the area, and particularly now since the women have passed away, who were either unfamiliar with the story or were like, "Wow, we didn't think it was that important."

But strangely, outside of Hampton Roads, the public is like, "I just can't believe this story I had no idea!" Or, even at NASA, "Well, I didn't really know." Even some of the NASA historians I spoke with were like, "I kind of thought there were a couple of women who were doing this," but they did not know the scope or the extent of it. This was something that started in 1935 when the five computers were hired at Langley.

I think there were just so many little bits and pieces to this story hidden in different places, and the people who were doing it, these women, and engineers even, who were just doing their jobs. It was totally normal, like, "Yeah, I was called up by my country to be a mathematician and that is what I did and that's it."

So I think for any number of reasons, people either knew about it and did not think it was a big deal or they had not found it. But there were so many women doing this work. There were women computers at NASA Glenn [Research Center in Cleveland], obviously in Houston and there were women at Ames [Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif.]. They were the computers. There were just a ton of women and it was no big deal kind of.

collectSPACE: In addition to being about these women, it is also a story about their being the computers, first for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and then for NASA. How did you decide how much to devote to the technical details of their work, and in a greater sense, the work being done at Langley?

Shetterly: Part of the thing about writing it was figuring out how much technical information to include. I had a lot of learning to do, but I thought the science was interesting. It is obviously critical to a key part of the story, but I had to figure out how interesting it would be to the general reader.

I started working on it in 2010. I would say it probably took three years of just research for me to just figure out how to tell the story. Really digging into these different strands of Virginia history, the history of these women.

When it started out, the obvious person to tell the story, to be the protagonist, was Katherine Johnson. I had known her growing up and within the Virginia and NASA Langely communities people knew her name. She was the obvious place to start.

But this is a huge story. There were so many women.

I think a lot of people, even now, kind of think [Johnson] was the only woman, or the only black computer, and there are so many women, black, white and other, who did this job.

It took a really long time of unearthing the details of all of these women, learning enough about the actual work that was going on at the time that Langley was doing. Going into these research reports and kind of connecting the dots with these women.

And reading up on my Virginia history. There is so much about Hampton that I didn't really know about Virginia and about World War II. That for me, was the most fascinating part of it.

So it took a really long time to get all this information and then it took a long time to figure out how to carve it back.

I think the first iteration of the book was a little more geeky. It was more about NASA and a technical history. It took time to figure out how to tell all the stories, to weave them together as one narrative and to tell it as much as I could through the eyes of the women as the protagonists of the story. It took a long time to unearth this narrative from what was an overwhelming amount of historical and technical information.

Continue reading this "Hidden Figures" Q&A with Margot Lee Shetterly at collectSPACE.

"Hidden Figures" by Margot Lee Shetterly was released by William Morrow, a division of HarperCollins, on Sept. 6.

Follow collectSPACE.com and Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2016 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.

In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.