SpaceX Dragon Departs Space Station with Mice, Other Experiments

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

SpaceX's Dragon cargo spacecraft is headed back to Earth from the International Space Station today (Aug. 26) with more than a ton of experiments and cargo bound for splashdown, including 12 mice.

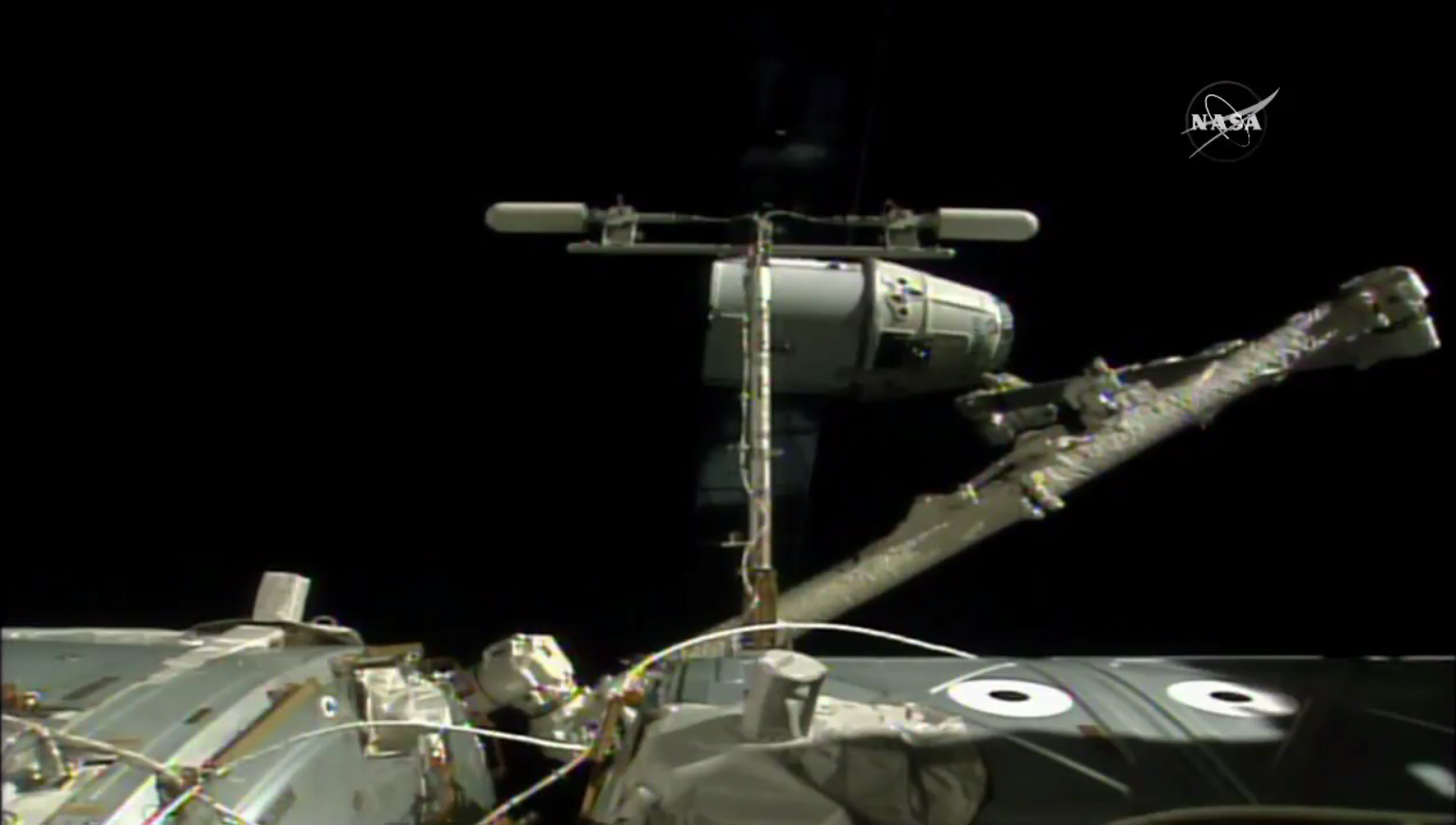

NASA astronaut Kate Rubins and Japanese astronaut Takuya Onishi released unmanned Dragon space capsule, packed with 3,000 lbs. (1,360 kilograms) of gear, into space at 6:11 a.m. EDT (1011 GMT) using the station's robotic arm. Now, the craft is moving a safe distance away from the station before blasting its engines to leave orbit and head back down to Earth.

That engine fire is scheduled for 10:56 a.m. EDT (1456 GMT), and by 11:47 a.m. EDT (1547 GMT), it should splash down in the Pacific Ocean off of Baja California, Mexico, to be retrieved by SpaceX employees. The descent and splashdown will not be broadcast live.

Article continues belowThe Dragon spacecraft arrived at the space station July 20, bringing experiments, science equipment, tools and supplies to the six crewmembers. Now, some of those experiments are on their way back home. NASA officials mentioned two, in particular: a mouse epigenetics study and a heart cells study. [Why Do We Send Animals to Space?]

According to NASA's experiments page, 12 male mice were sent to live on the space station for 30 days, and upon the animals' return, researchers will look for changes in DNA from the mice's organs. (Researchers will also analyze the DNA of offspring mice created with the spacefaring mice's sperm.) The space station crew transferred the mice from their habitat cage unit to a transportation cage unit Tuesday in preparation for the trip home.

The heart cells study analyzed live, beating heart cells on the space station to see if there would be any impact on the heart, on the cellular level, from the time spent in orbit. Scientists already know that, physically, astronauts' hearts become more spherical and lose muscle mass while in space, and that those changes are reversed when astronauts get back to Earth.

The astronauts have spent a busy week packing homebound supplies into the spacecraft after a day off to make up for extra activity on the weekend after a spacewalk last Friday (Aug. 19). That's when Rubins and fellow NASA astronaut Jeff Williams installed the first of two International Docking Adapters that the Dragon spacecraft brought along in its trunk. The adapter will allow future spacecraft to dock directly with the U.S. side of the space station instead of needing to be grappled by the station's robotic arm.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Next Thursday (Sept. 1), Williams and Rubins will again head back out on a spacewalk to retract a thermal control radiator and install at least one high-definition camera onto the station's exterior.

Then, on Sept. 6, Williams and Russian cosmonauts Oleg Skripochka and Alexey Ovchinin will leave the space station after five and a half months on board — capping off Williams' record-setting 534 cumulative days in space.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.