Mercury Transit Timeline: The Stages of Today's Rare Celestial Sight

Mercury will cross the sun's face from Earth's perspective Monday (May 9) for the first time since 2006, and the last until 2019.

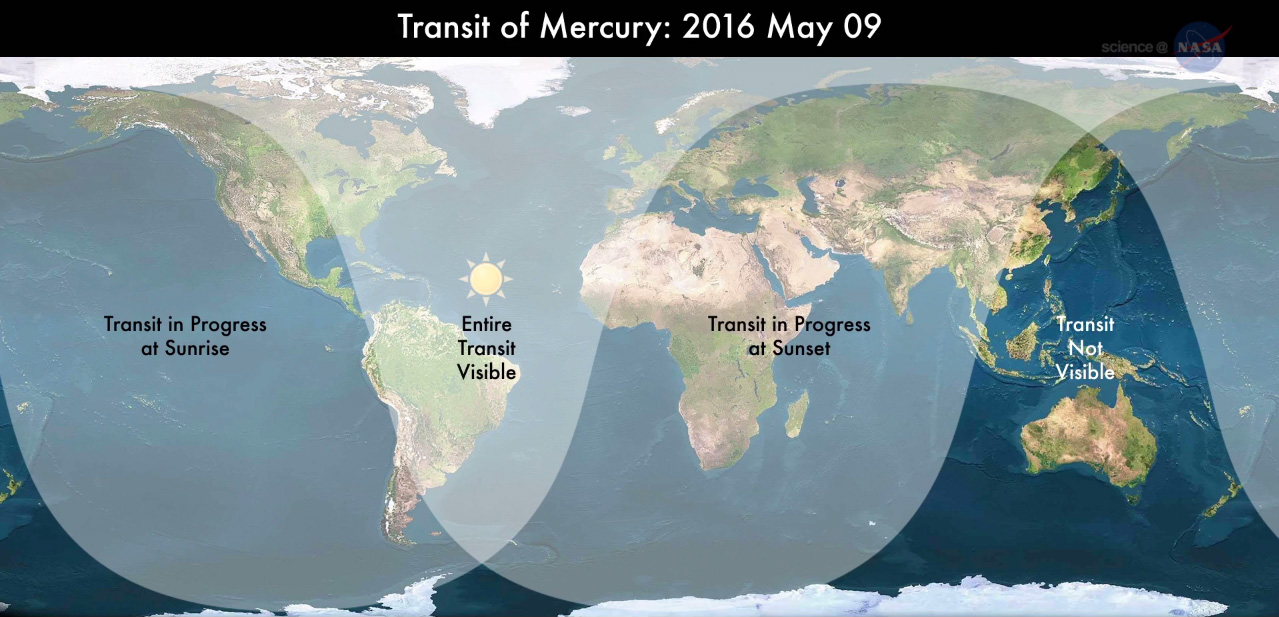

You can watch the 7.5-hour Mercury transit first-hand through a telescope, provided you have the proper solar filters. (Never look directly at the sun without such protection; blindness can result.) Or you can catch the event online; NASA, for example, will broadcast near-real time views from the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) spacecraft at the agency's transit page.

The Slooh Community Observatory will host a free, live webcast of the Mercury transit from 7 a.m. EDT to 2:45 p.m. EDT (1100 to 1745 GMT). You can also watch the webcast live on Space.com, courtesy of Slooh. [The Mercury Transit of 2016: How to See It and What to Expect]

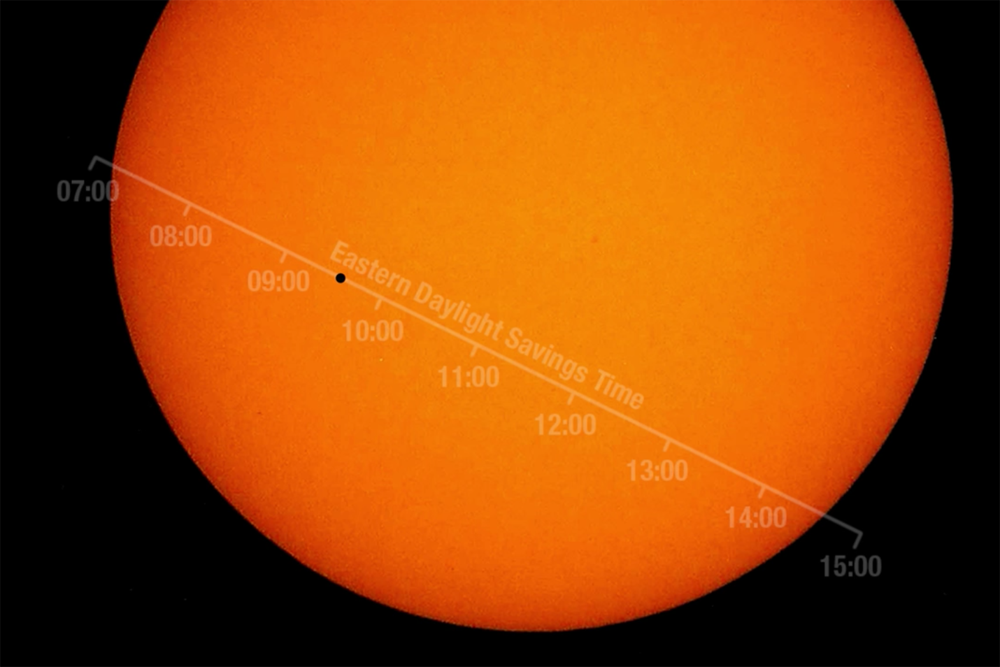

Here's how the transit will proceed as seen by SDO, according to Dean Pesnell, project scientist for the spacecraft at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. The times will vary slightly depending on where you are in the world; SDO sees events slightly before Earth because it is closer to the sun.

Corona contact (roughly 6:21 a.m. EDT; 1021 GMT): This event is visible only from space. The sun is surrounded by a superheated plasma atmosphere known as the corona. The corona is so diffuse that it can be seen only during a solar eclipse or from space, if the sun's light is blocked out. Mercury will enter the edge of the sun's corona about an hour before "first contact."

First contact (7:21 a.m. EDT, 1121 GMT): When the edge of Mercury touches the edge of the sun for the first time.

Second contact (slightly after 7:21 a.m. EDT, 1121 GMT): Very soon after first contact, when Mercury moves completely onto the sun's disc.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As Mercury separates from the edge of the sun, look for the "black drop" effect — when a thin line appears to connect Mercury to space itself. Pesnell said this occurs because telescope optics are very slightly less than perfect. On Monday, the effect may not be as pronounced as viewers saw with Venus transits in 2004 and 2012, because the "black drop" may be produced in part by a planet's atmosphere. Mercury has just a thin "exosphere," while Venus has an extremely thick atmosphere.

Transit midpoint (11:20 a.m. EDT, 1520 GMT): When Mercury is halfway across the face of the sun.

Third contact (slightly before 2:50 p.m. EDT, 1850 GMT): When Mercury contacts the edge of the sun on its way off the solar disc. Again, look for the "black drop" effect.

Fourth contact (2:50 p.m. EDT, 1850 GMT): When Mercury leaves the sun's disc altogether.

Last corona contact (roughly 3:50 p.m. EDT, 1950 GMT): When Mercury leaves the sun's corona. Again, this event is visible only from space.

Pesnell added that scientists are hoping to see Mercury pass over a solar flare, which has never been observed before from space. "It would be a nifty way of knowing where that flare was precisely on the sun," he said.

This is unlikely to happen, however, because most solar activity occurs in the northern half of the sun and Mercury is passing through southern regions, Pesnell added.

Editor's note: Visit Space.com on Monday to see live webcast views of the rare Mercury transit from Earth and space, and for complete coverage of the celestial event. If you SAFELY capture a photo of the transit of Mercury and would like to share it with Space.com and our news partners for a story or gallery, you can send images and comments in to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.