Surprising Shifts in Pluto Atmosphere Point to Gravity Waves (Photos)

Unexpected variations in the brightness of Pluto's wispy atmosphere may be caused by gravity waves, scientists say.

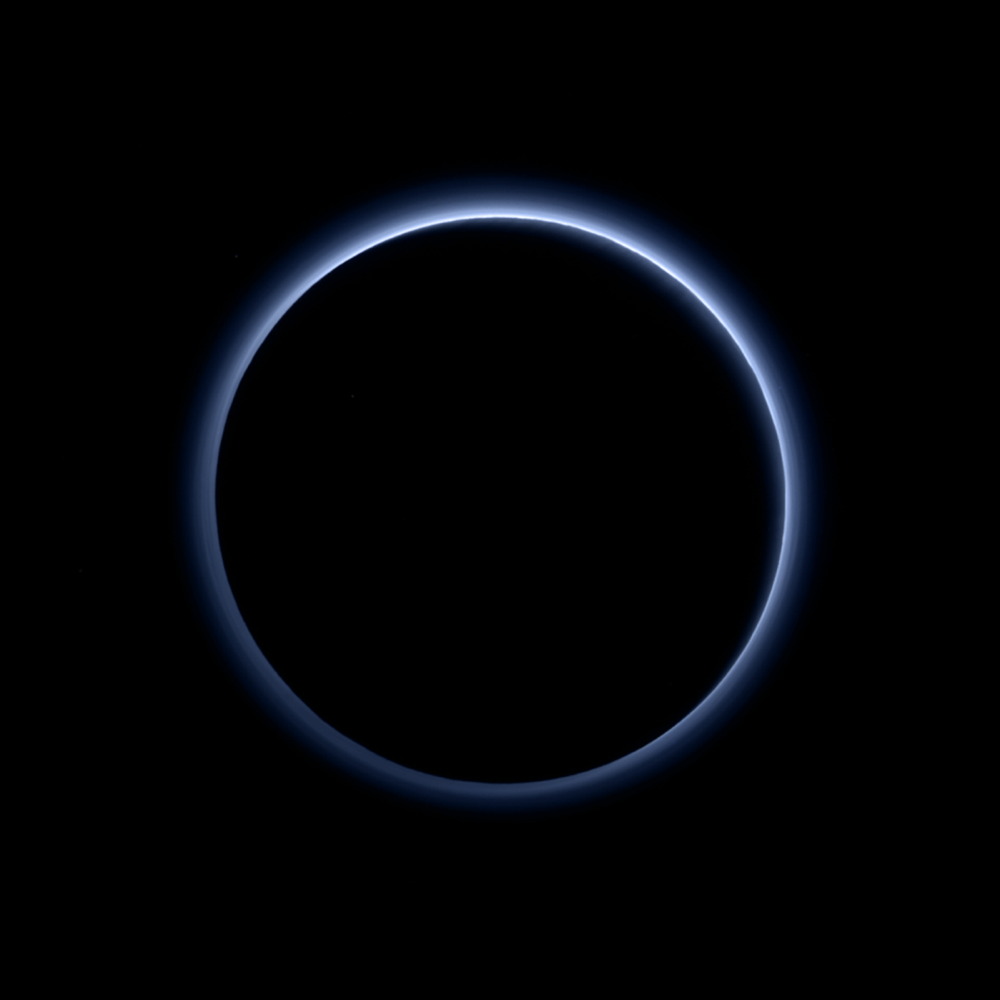

Newly analyzed images captured by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft, which flew past Pluto last July, show that the dwarf planet's haze layers can change in brightness depending on lighting conditions and viewing perspective. However, the haze keeps the same vertical structure.

"The brightness variations may be due to buoyancy waves — what atmospheric scientists also call gravity waves — which are typically launched by the flow of air over mountain ranges," NASA officials wrote last week in a description of the images, which were captured by New Horizons' Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) during the flyby on July 14, 2015.

"Atmospheric gravity waves are known to occur on Earth, Mars and now, likely, Pluto as well," the officials added.

Gravity waves are not the same thing as gravitational waves, which are ripples in the fabric of space-time first predicted by Albert Einstein in his theory of general relativity. The first-ever direct detection of gravitational waves was announced earlier this year by scientists with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO.

The LORRI images were taken in intervals ranging from roughly 2 to 5 hours each, revealing layer brightness variations of about 30 percent. However, the height of the layers was the same in each image, scientists said.

"When I first saw these images and the haze structures that they reveal, I knew we had a new clue to the nature of Pluto's hazes," Andy Cheng, LORRI principal investigator from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, said in the same NASA statement. "The fact that we don't see the haze layers moving up or down will be important to future modeling efforts."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The New Horizons mission has made a number of interesting discoveries about Pluto's atmosphere. For example, flyby observations revealed that Pluto's hazes extend at least 120 miles (200 kilometers) above the dwarf planet's surface — far higher than models had predicted.

The hazes also have a blue tint, which comes from complex organic molecules known as tholins that scatter light at blue wavelengths.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.