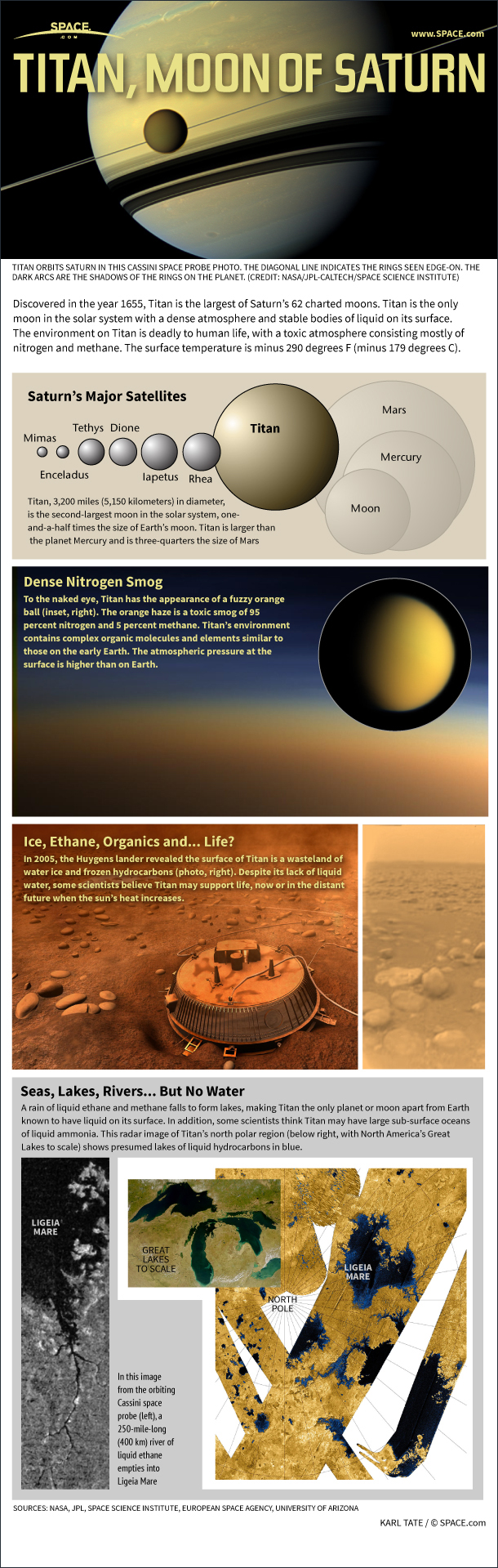

Tallest Peak on Saturn's Huge Moon Titan Identified (Photo)

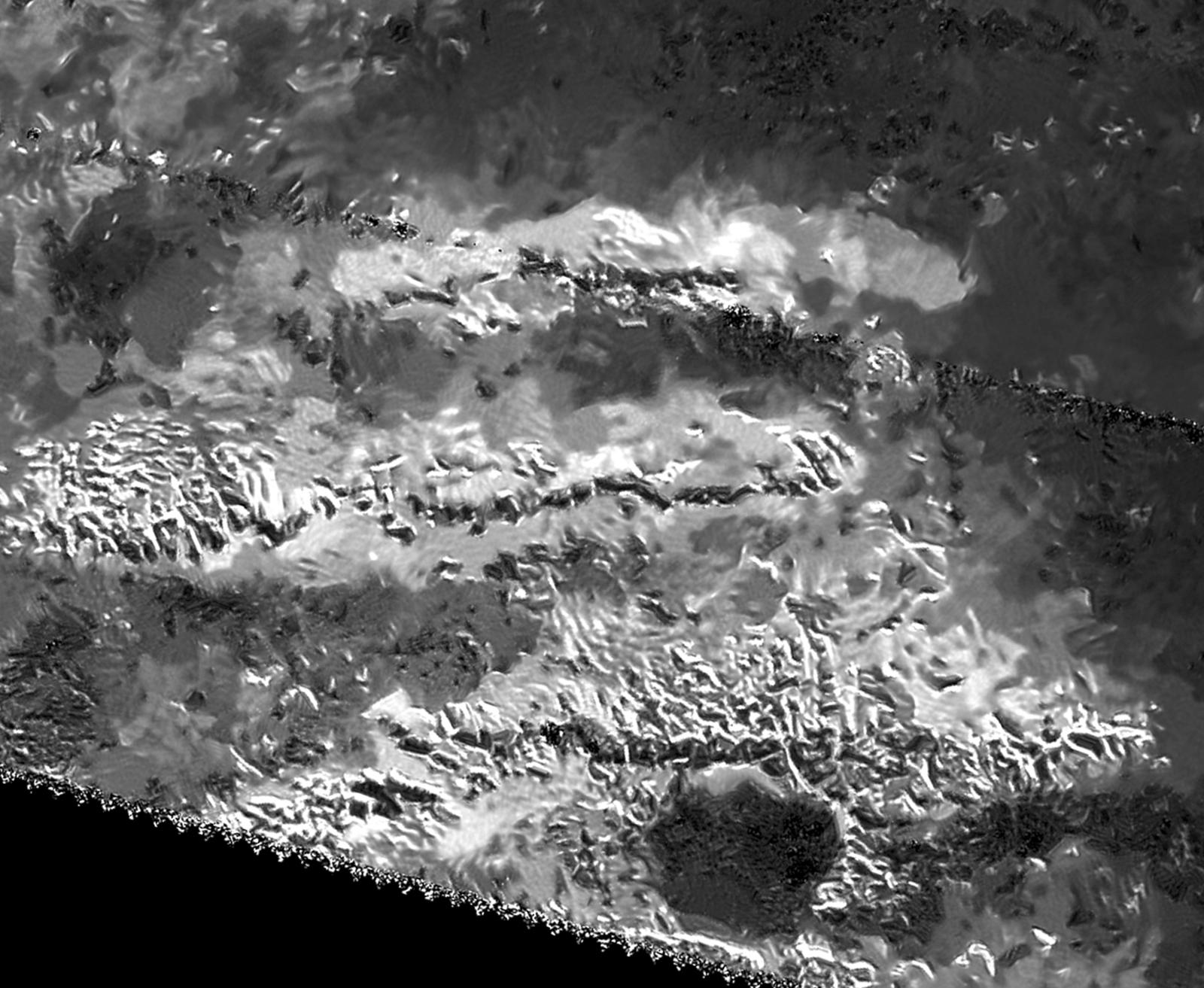

Titan's tallest peak rises nearly 11,000 feet (3,350 meters) into the huge Saturn moon's hazy skies, new observations by NASA's Cassini spacecraft suggest.

Images and radar data taken by Cassini peg a 10,948-foot-tall (3,337 m) mountain in an equatorial range called Mithrim Montes as Titan's likely loftiest peak, mission scientists announced today (March 24) at the 47th annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

"It's not only the highest point we've found so far on Titan, but we think it's the highest point we're likely to find," Stephen Wall, deputy lead of the Cassini radar team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in a statement. [Amazing Photos: Titan, Saturn's Largest Moon]

A number of other 10,000-foot (3,050 m) peaks stud Titan's surface, mostly in spots close to the equator. The existence of such big mountains suggests that tectonic forces could be shaping the 3,200-mile-wide (5,150 kilometers) moon's landscapes today, researchers said.

"There is lot of value in examining the topography of Titan in a broad, global sense, since it tells us about forces acting on the surface from below as well as above," study leader Jani Radebaugh, a Cassini radar team associate at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, said in the same statement.

Just what could be powering Titan's mountain-building activity remains a mystery, scientists said; possible energy sources are Saturn's powerful gravitational pull, the cooling of Titan's icy crust and quirks of its rotation.

Titan's big mountains cast the moon's resemblance to Earth in starker relief. For example, the satellite is surrounded by a thick, nitrogen-dominated atmosphere, as Earth's is. And Titan is the only body in the solar system besides Earth known to host stable bodies of liquid on its surface — though Titan's lakes and seas are composed of hydrocarbons, not water.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Indeed, if life exists on Titan, it will almost certainly be very different from Earth's because of the preponderance of hydrocarbons and lack of liquid water on the surface, most scientists say.

Titan does probably have liquid water, and lots of it, but it's buried deep inside the moon, in a global subsurface ocean. Scientists think the satellite's bedrock is composed of water ice, which is much softer than the actual rock that makes up Earth's bedrock; this helps explain why mountains on Titan don't get as tall as Mount Everest (29,029 feet, or 8,848 m) and other big Earth peaks.

The $3.2 billion Cassini-Huygens mission, a joint effort involving NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency, launched in 1997 and arrived in the Saturn system in 2004.

The Cassini mothership carried a lander called Huygens, which touched down on the surface of Titan in January 2005 and sent data home to Earth for about 90 minutes. Cassini, meanwhile, will continue to study Saturn and its many moons until September 2017, when it ends its highly successful mission with an intentional death dive into the gas giant's thick atmosphere.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.