Gods Among the Stars: Why Egyptian Names Grace Comet 67P

How did the regions on Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko get all those beautiful Egyptian names? A Rosetta scientist recently discussed how those divine labels were chosen.

When the Western world began unearthing ancient Egyptian cities and decoding the remnants of those cultures, once-hidden histories were illuminated for a new group of people. Now, scientists are trying to excavate an object of even greater antiquity: a comet traveling around our sun.

The Rosetta probe has been orbiting Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko (Comet 67P, for short) for nearly a year, and with images sent back to Earth from the spacecraft, scientists are becoming intimately familiar with the comet's surface, which they have divided into 19 separate parts and named after Egyptian gods. [Photos: Europe's Rosetta Comet Mission in Pictures]

In an article posted Tuesday (July 15) on the European Space Agency's Rosetta blog, M. Ramy El-Maarry, a scientist from the University of Bern, wrote about how the Rosetta team decided to continue with the theme and name the newly discovered regions of Comet 67P after Egyptian gods and goddesses. In addition, the article discussed the results of a new paper by El-Maarry and colleagues that continues to probe the history of the comet, and how it developed so many distinct features. .

The Rosetta probe is named after the Rosetta Stone, a hunk of rock inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphics that allowed anthropologists to decode the language of a long-gone civilization (the rock itself was given the old name of the Egyptian city where it was found).

"Just as the Rosetta Stone provided the key to an ancient [civilization], so ESA's Rosetta spacecraft will unlock the mysteries of the oldest building blocks of our Solar System — the comets," according to the ESA website.

Ancient Egyptians had "so many dieties in their long history" that the team had plenty of names to choose from, El-Maarry said in the article. "Moreover, many of the names were catchy, easy to remember, and more importantly, easy to pronounce. I remember we initially tried using names of ancient cities and we were coming across a lot of names that were very difficult to wrap your tongue around, even for an Egyptian like me!"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Comet 67P has two distinct lobes, attached by a thinner neck. The larger of the two lobes, the body, and the smaller lobe, known as the head, give the comet a look similar to a plastic rubber duck. It appears as though this double-lobed shape is common among comets.

"We picked Hapi for the neck since Hapi is the Nile god, and we figured that he should separate the lobes in the same way that the Nile splits Egypt into an eastern and western side," El-Maarry said in the statement.

Regions on the body lobe of the comet are named after Egyptian gods, and regions on the head are named after goddesses, according to El-Maarry. So far there are 19 regions, which fall into five categories: dust-covered regions (Ma'at, Ash and Babi); one region covered in pits and circular structures that are underlain with brittle materials (Seth); regions with big depressions (Hatmehit, Nut and Aten); smoother regions (Hapi, Imhotep and Anubis); and those with rocklike surfaces (Maftet, Bastet, Serqet, Hathor, Anuket, Khepry, Aker, Atum and Apis).

The region names are mostly those of lesser-known Egyptian gods and goddesses, which El-Maarry said was intentional because many of the more popular deity names have already been used by other space missions. Osiris, for example, is the name of an instrument onboard Rosetta, as well as a NASA mission scheduled to launch in 2016 that will bring samples of asteroids back to Earth.

While the surface of the comet may appear uniformly rocky to the untrained eye, researchers like El-Maarry are spotting lots of variation, which suggests the comet has had a very active history As comets move toward the sun, previously frozen materials sublimate into gas, which could cause quick disruptions in the rocky material that makes up the comet.

Aten, for example, is a long, slim region on the body of the comet named after an Egyptian god of the sun. The Aten region contains a long depression with sharply sloping sides, bordered by the dusty, brittle material in Ash and Babi. In a new paper, El-Maarry and colleagues suggest the depression could have been caused by a rapid and perhaps violent burst of activity (perhaps like the recently studied sinkholes on the comet, which may arise from ice melting under the surface). Meanwhile, the paper suggested that the unique region known as Seth may extend farther under Ash and Babi than previously thought.

The new paper also looks at the boundary of smooth Anubis and rocky Atum, which features curved lines running parallel to each other, where the researchers say the surface may have folded, or where large flat terraces may be buried.

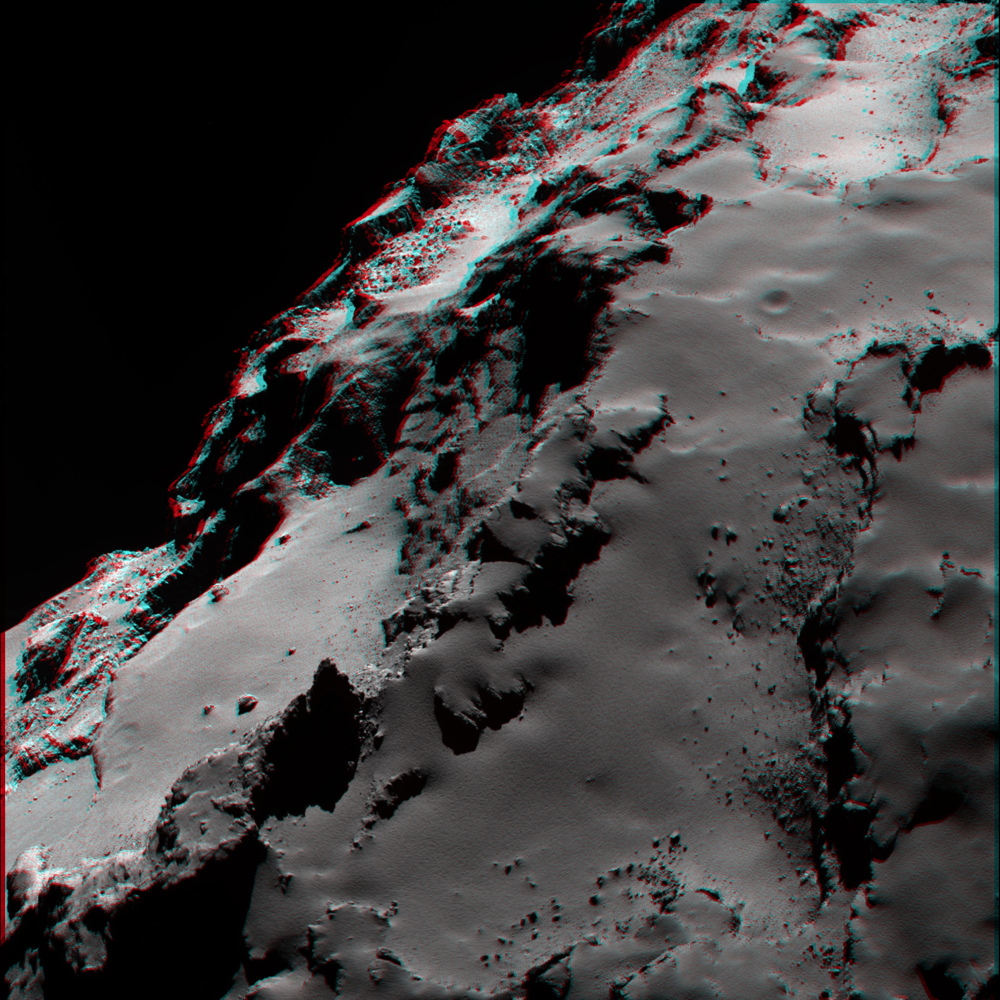

Looking for subtle changes in the landscape of the comet can be tricky in two dimensions, so Rosetta scientists are also using 3D "anaglyphs," or images created by combining images taken of the same region, a few seconds apart (to get the 3D effect, you'll need red-blue or red-green 3D glasses — you can see more 3D images of Comet 67P here).

The comet region known as Imhotep is a long, smooth patch on the comet's larger lobe that is named after a man who lived in ancient Egypt and was "one of the most brilliant figures of the ancient world as a scientist, engineer, and a physician," El-Maarry said. "Luckily for us, there were no Nobel prizes in ancient Egypt so when Imhotep died, he was deified by ancient Egyptians to credit his accomplishments, which meant we could actually use his name as a nice tribute from our side!" he said.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter