Pluto Flyby Occurs 50 Years After 1st Mars Encounter

How's this for timing? NASA's New Horizons spacecraft is winging past Pluto this morning (July 14) exactly 50 years after the first robotic visit to Mars.

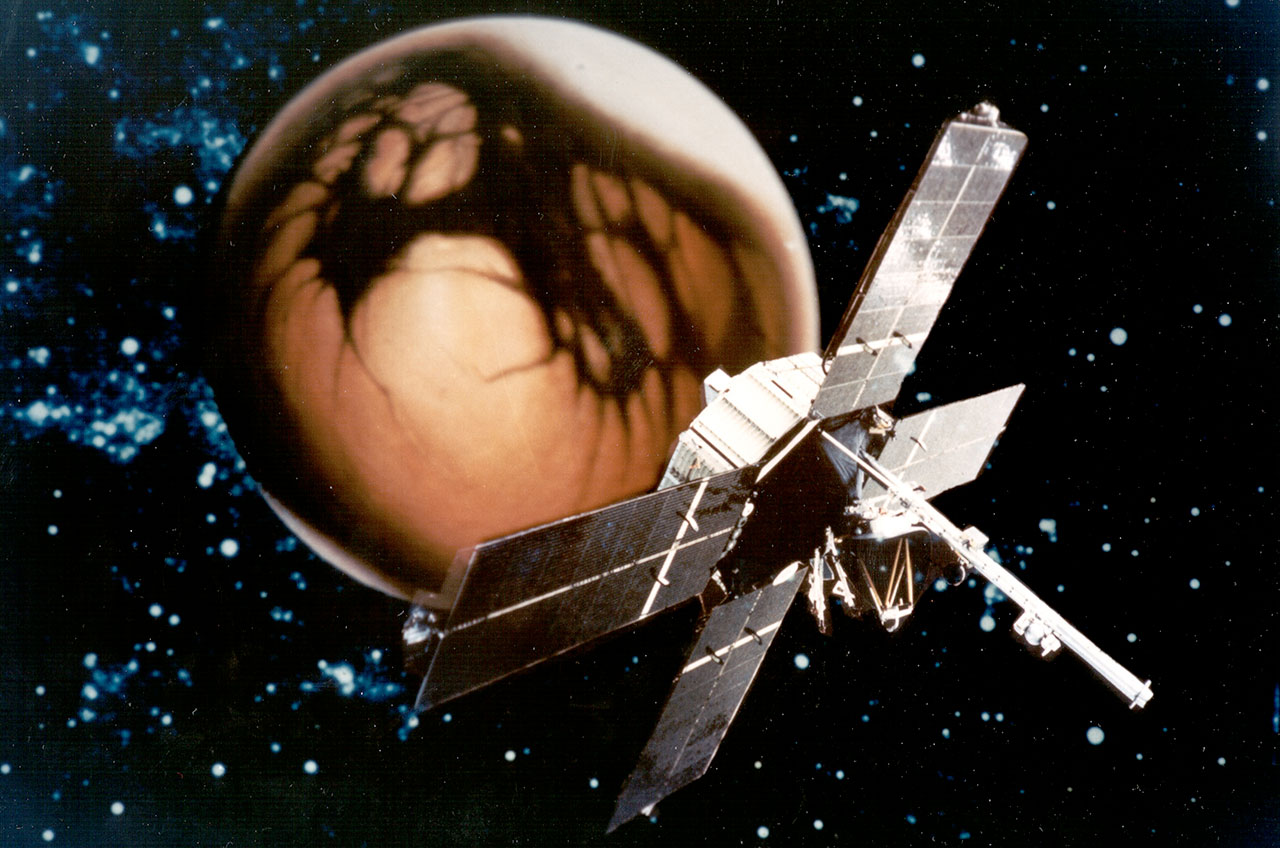

On July 14, 1965, NASA's Mariner 4 probe flew by the Red Planet, becoming the first spacecraft ever to capture up-close looks at another planet. (NASA's Mariner 2 spacecraft gathered data but no images when it zoomed past Venus in December 1962.)

"You couldn't have written a script that was better," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, told Space.com. [New Horizons' Pluto Flyby: Complete Coverage]

NASA and the New Horizons team are honoring the Mariner 4 mission and its space-exploration legacy: Three Mariner 4 veterans are on-site at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, today, soaking up the flyby scene at mission control. You can watch NASA's Pluto flyby coverage live today, beginning at 7:30 a.m. EDT (1130 GMT).

Different times

Space exploration was a different beast back in 1965. The United States and the Soviet Union were racing to send men to the moon and to explore the solar system. Science-fiction stories that envisioned humanoid life on Venus and Mars could not be dismissed out of hand.

But before Mariner 4, only one spacecraft had ever flown past another planet successfully: Mariner 2, which had no imaging capability.

"We learned a great deal, and I think the most impressive thing was how little we actually knew about Mars," Ed Smith, one of Mariner 4's instrument leaders, told Space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It’s like the Pluto mission — somebody was commenting on that recently — and it’s for the same reason," Smith added. "Mars is fairly small, and it’s far from Earth. The features on the surface [when seen by telescope] are almost the same size as variations in Earth’s atmosphere."

This meant that Mariner 4 served as a reconnaissance mission. Essential questions it would answer included how thick the Martian atmosphere is, and what kind of surface the planet possesses. [7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars]

Barren Red Planet surface

Smith headed Mariner 4's magnetic-field team, which was responsible for finding out if Mars has a magnetic field and radiation fields similar to those of Earth. He and his colleagues discovered magnetic fields, but they were very weak ones, possessing just 0.01 percent of Earth's magnetic-field strength.

To investigators' surprise, however, Mars deflects the solar wind (the constant stream of particles from the sun), like Earth does. But the mechanism is different. Earth's magnetic field and thick atmosphere serve as radiation shields, whereas on Mars, a layer in the upper atmosphere (called the ionosphere) deflects some of the particles.

It's not a perfect defense, however, as radiation levels on Mars far exceed those of Earth.

Mariner 4's images showed craters, which surprised investigators because they thought Martian winds would erode these structures away. But the resolution on the on-board television camera was quite low by today's standards, Smith said, meaning the smaller and more eroded craters, valleys and canyons weren't visible.

Nevertheless, the weak magnetic field and the fresh craters pointed to little or no interior activity such as plate tectonics, Smith said. Even though NASA's Mariner 9 mission discovered vast volcanoes and valleys on Mars in the early 1970s, these features appear to be mostly dormant, except for wind erosion.

"Many of the things we saw have not been overturned [in later missions], but more has been added," Smith said. "They did in fact find out there had been much more activity on Mars."

Morse code from Mars

Mariner 4 returned reams of data and 22 images from Mars, but the pace of sending information back was glacial by today's standards. The antenna that was used sent back the equivalent of "Morse code" from Mars, Smith said, at very low bit rates.

At times, only the Australian dish of NASA's Deep Space Network could communicate with Mariner 4. The data it collected took two weeks to arrive in the United States because it had to be shipped on magnetic tapes, sometimes leading to mysterious gaps that puzzled investigators until the new information arrived.

While Mariner 4's mission ceased in 1967, Smith (who is still at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California) has helped explore much more of the solar system. As a magnetic-field investigator, he has helped make observations at Jupiter and Saturn (as part of the teams on NASA's Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11 and Cassini missions) and the sun (the Ulysses mission). Smith is also working on NASA's Juno orbiter, which will arrive at Jupiter in 2016.

Last year, Smith got a blast from the past when he worked with a citizen science team that briefly re-established communications with NASA's long-dormant ISEE-3 spacecraft. Smith worked on the magnetic-field instrument for the probe, which was launched in 1978 as the International Cometary Explorer. To his delight, the instrument was still working after 36 years in space.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.