Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Satelliteobservations have confirmed how a certain type of star explosion occurs andrevealed a previously unknown stage of radiation release during the stellarburst.

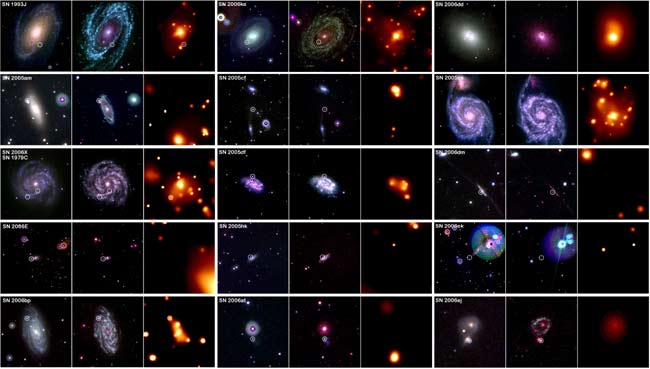

UsingNASA's Swiftsatellite, astronomers observed two dozen supernovas [image]shortly after they happened. Two, especially, were of special interest.

One, calledSN2005ke [image],was a Type1a supernova. These explosions are thought to occur when small, dead starscalled white dwarfs siphongas from the atmosphere of either another whitedwarf or a redgiant star. The white dwarfs accumulate matter until they reach a criticalmass of 1.4 solar masses and explode.

Astronomersuse Type 1a supernovas as "standardcandles" to measure cosmic distances because all Type 1a's are thoughtto blaze with equal brightness at their peaks, although this has beenchallenged by recent observations.

X-ray andultraviolet observations by Swift showed shock waves from SN2005ke ramming intovery dense gas that could have only come from a red giant star, confirming atleast one of the Type 1a formation scenarios.

"Theonly explanation that we have for X-ray and ultraviolet emission is that thisType 1a supernova has to have a companionstar. This companion has to be a massive star that is losing a lot of massfrom its stellar wind particles," study leader Stefan Immler of NASAGoddard Space Flight Center in Maryland told reporters at a press conference.

Also ofinterest was SN2006bp [image],a TypeII supernova created when a massive star ran out of fuel and collapsed underits own gravity. Swift detected X-ray radiation immediately after the explosionthat had never been seen before and which faded within days. The researcherswere also surprised to find evidence of hot gas lingering near the explodedstar's remains. This suggests that the star's radiation did not create a cavityaround the star before the explosion, as is commonly thought.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Thatwas our surprise finding," Immler explained. "We had expected thatthe stellar wind blows a cavityaround the star and that there is nothing there that can be shock-heated tohigh enough temperatures to give off X-rays."

Onepossible explanation for the anomalous gas, Immler said, is that the exploded star might have been a redsupergiant whose stellar wind was slow and dense.

"That'sjust the nature of the stellarwind, if it's a slow enough, dense enough stellar wind, it will not blow ahole in the environment," he said.

Theresearch was presented last week at the annual meeting of the High EnergyAstrophysics Division of the American Astronomical Society in San Francisco.

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

- Core of Supernova Goes Missing

- Strange Supernova Defies Theory

- Supernova Photographed in Earliest Stage

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.