Wild Weather of Distant Stars May Affect Chances for Alien Life

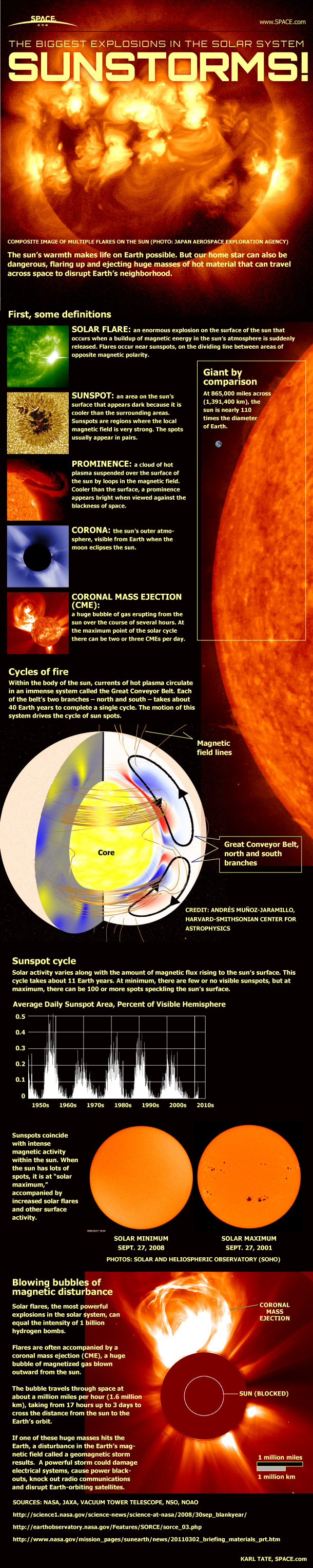

Earth regularly endures violent ejections of material from the sun, but could similar eruptions in other solar systems make alien planets inhospitable to life?

Two telescopes in the Mojave Desert are searching for these bursts of activity from stars, which could affect the development of distant planets and their potential for life. When material streams off of a star on a daily basis, it produces what scientists call "space weather." But the sun's weather may be mild compared to that of the most plentiful stars in the galaxy, M-dwarfs.

"As we're finding planets around M-dwarfs, they're going to be exposed to much more active space weather," Jackie Villadsen told Space.com. A graduate student at the California Institute of Technology (CalTech) Department of Astronomy, Villadsen is working on the Starburst program with Gregg Hallinan, also of CalTech's astronomy department. [The Sun's Wrath: Worst Solar Storms in History]

Point and wait

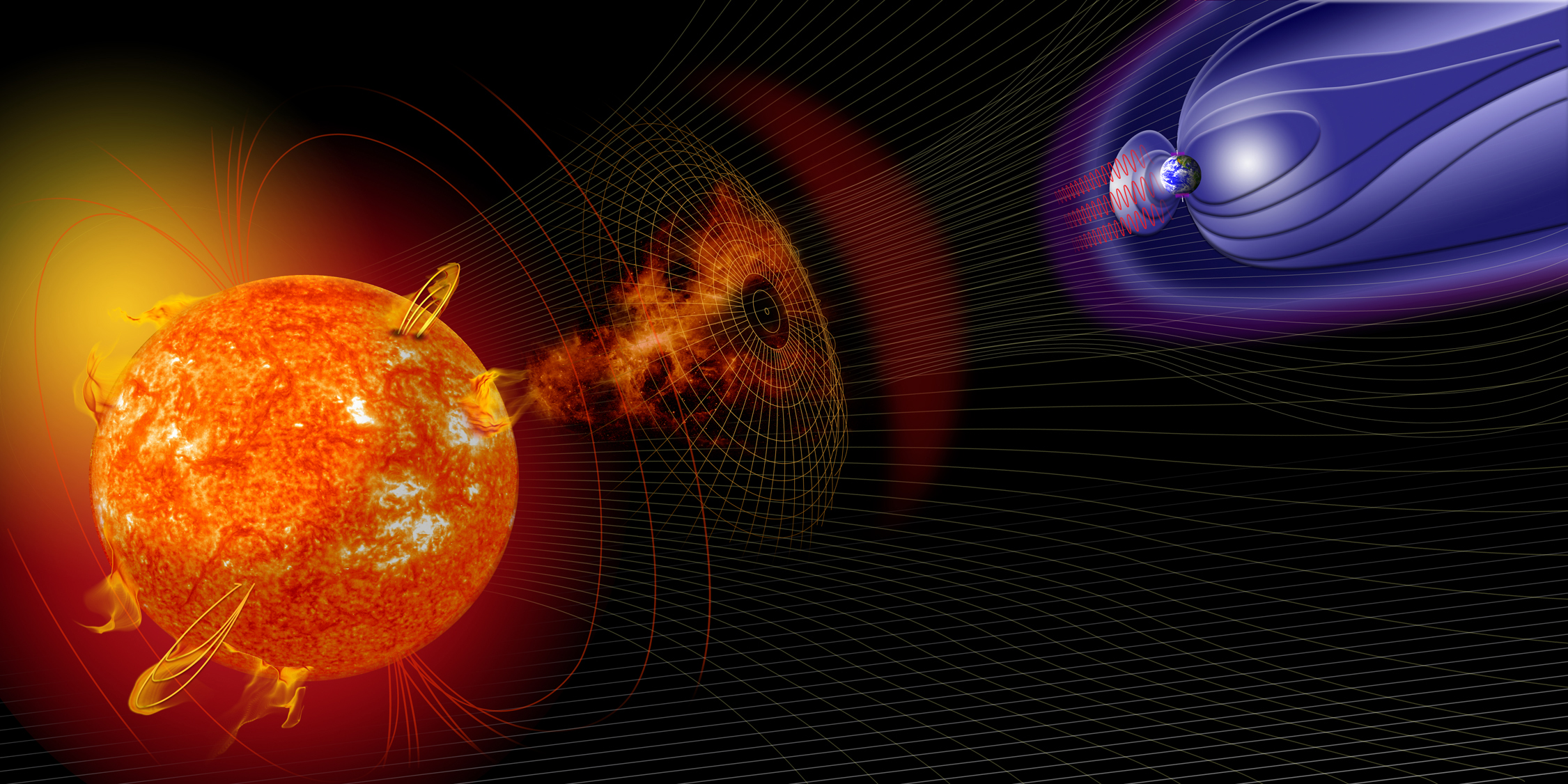

Every day, charged particles carried from the sun by the solar wind bombard Earth. Sometimes, however, this space weather can become more extreme as the sun shoots bursts of plasma known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs) that have the potential to knock out power grids and satellites on Earth.

Without its magnetic field, the planet would experience even greater effects from these CME's: charged particles could strip the planet's ozone away for years at a time, allowing harmful radiation to reach the surface.

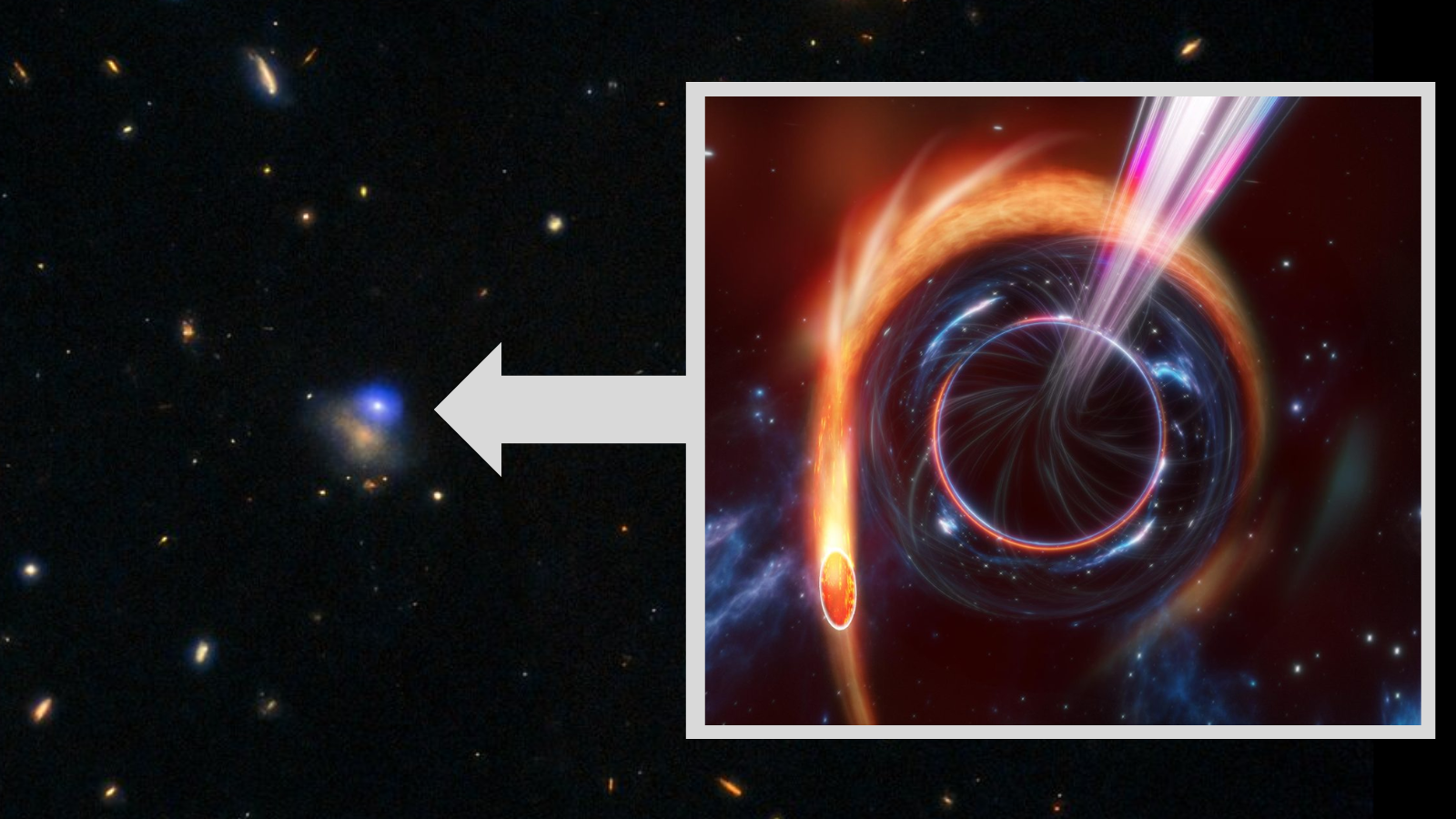

Because the sun is considered a typical star, it's likely that planets around other typical stars must also endure CMEs and space weather.. Of particular interest are planets surrounding M-dwarf stars, which are smaller than the sun and far more long lived. Also known as red dwarfs, M-dwarfs make up approximately 70 percent of the stars in the Milky Way, and some scientists suggest there may be as many as one planet for every red dwarf star.

Though the long lives of M-dwarfs may provide enough time for life to evolve on planets in their systems, their extreme space weather may threaten those chances. Sudden flashes of brightness from the surface of a star, called flares, often precede CME's, and flares on red dwarfs are up to a thousand times more energetic than those on the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For all their power, flares can be difficult to register. They appear at random, with essentially no warning. Studies of CMEs on the sun are possible thanks to the array of telescopes dedicated to monitoring Earth's closest star. Searching for them on nearby stars requires similar dedication.

In order to better understand space weather outside of the solar system, on M-dwarfs as well as other types of stellar systems, Villadsen is studying 15 stars over two and a half years with two radio antennas at the Owens Valley Radio Observatory in California. Of the 15 targets, eight are red dwarfs.

By keeping the stars in almost continual observation each evening, the scientists will be able to watch for the serendipitous explosions that will shed light on space weather around other stars.

"To find these things, we really need to point at another star and wait," Villadsen said.

Finding a zoo

Although flares have been observed on other stars, no extrasolar CMEs have been identified. So the properties of extrasolar CMEs remain a mystery. [The Biggest Solar Flares of 2015]

"It's incredibly hard to detect with just about any method," Villadsen said.

However, the sun demonstrates a relationship between strong solar flares and CMEs that other stars should replicate, she said. The selected targets are the closest flare stars within 7 light-years, which should mean these stars frequently spew CMEs.

If the relationship between flares and CMEs scales for other stars — and Villadsen said she expects that it does — the targets should experience an extremely high rate of CMEs. Incidents such as the Carrington event, a powerful 1859 solar flare that resulted in a brilliant aurora and disrupted telegraph activity, could occur daily on these planets.

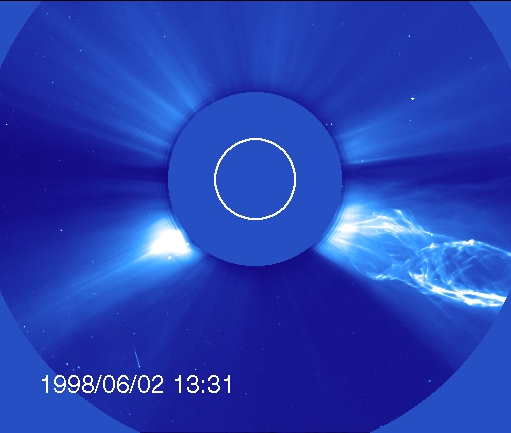

To study CMEs ejected by the sun, spacecraft create a fake eclipse, blocking out the main body to allow scientists to see the outer atmosphere. Other stars aren't nearly as well resolved, making it impossible to see the diffuse outer layer in optical light from so far away. So, instead of searching in visible wavelengths, the scientists intend to study radio emissions from the stars, watching for activity that mimics CMEs on the sun in that spectrum.

In addition to the observations made at Owens Valley, simultaneous observations will be made on occasion with other telescopes. These include the Very Large Array and the Very Long Baseline Array, whose greater sensitivities will provide a better understanding of the activity on these distant stars. Other observations will be triggered when the Starburst project detects large flares.

The observations should reveal multiple events on the active stars, which would allow the team to identify and characterize CMEs.

"We'll find a whole zoo of different sources of events," Villadsen predicted.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky