Newfound Alien Planet Is One of the Farthest Ever Detected

A NASA telescope has co-discovered one of the most distant planets ever identified: a gas giant about 13,000 light-years away from Earth.

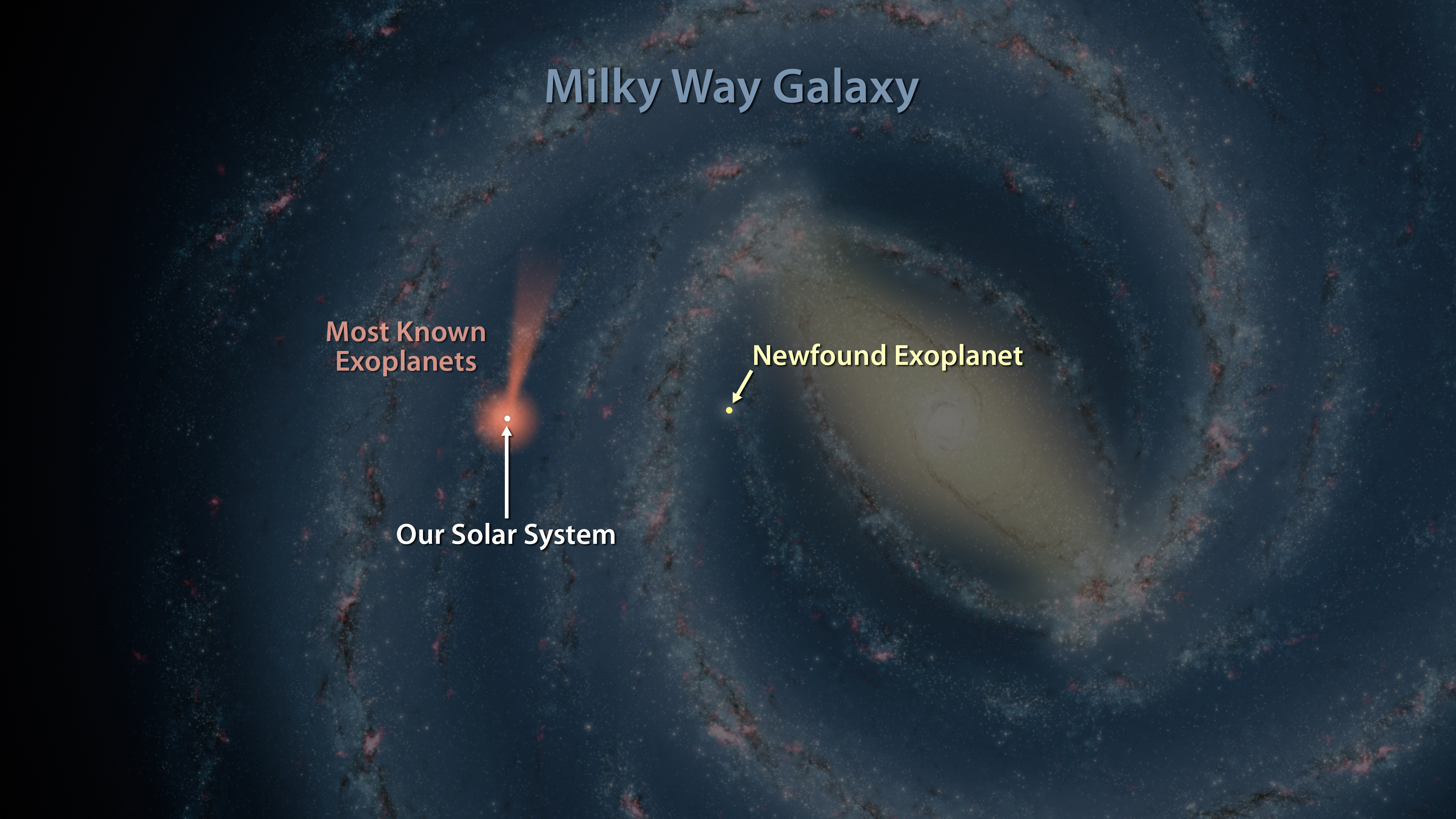

The technique used by the Spitzer Space Telescope, called microlensing, is so new that it has only yielded about 30 planet discoveries so far. But the telescope's potential for finding far-away worlds is vast, NASA said in a statement. And as astronomers begin to chart the location of these distant bodies, it will provide a sense of where planets are distributed in Earth's Milky Way galaxy.

"We don't know if planets are more common in our galaxy's central bulge or the disk of the galaxy, which is why these observations are so important," Jennifer Yee, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in a NASA statement. Yee is the lead author on one of three new papers describing the discovery. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

Magnified starlight

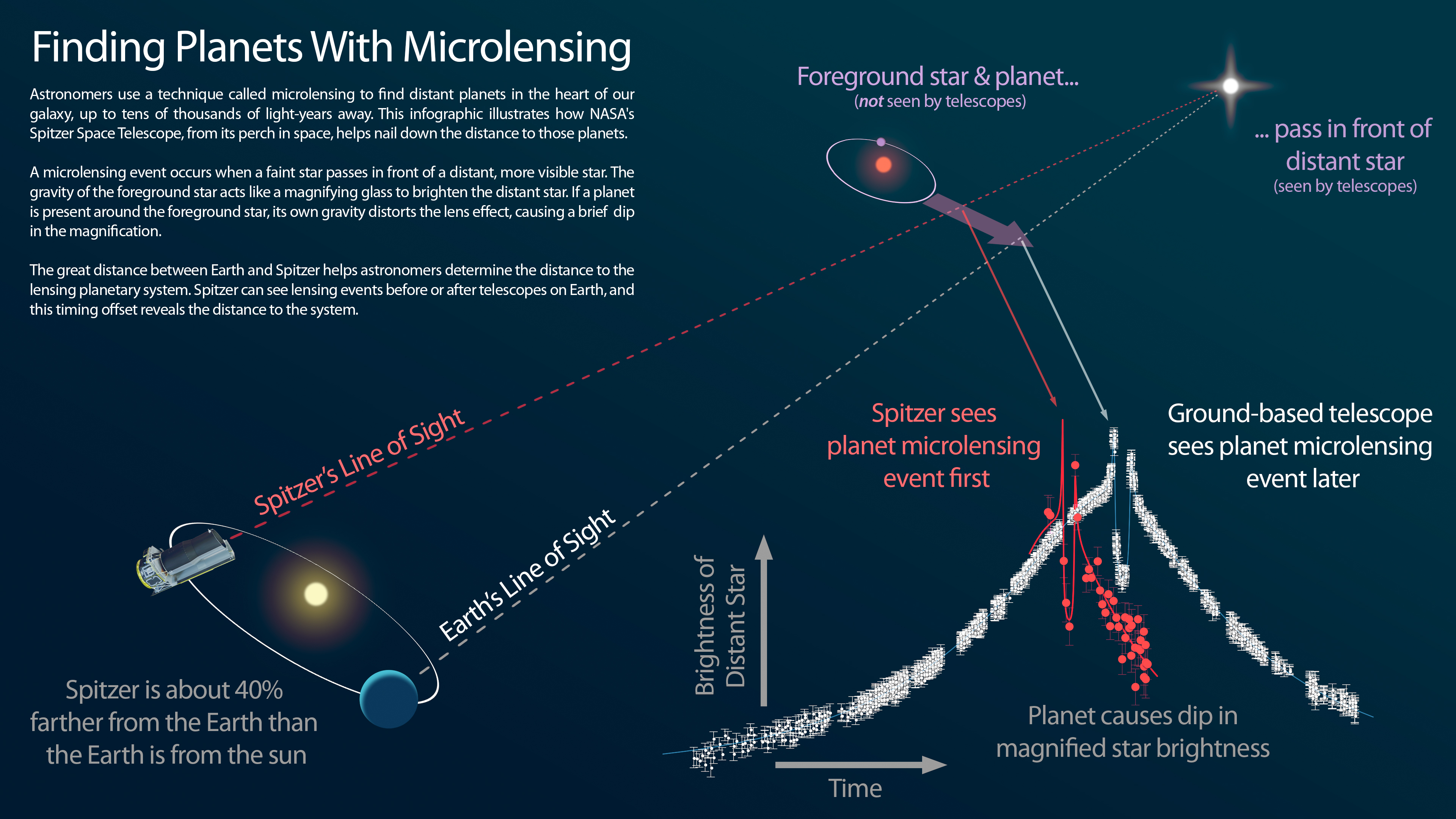

Microlensing happens when one star travels in front of another from the perspective of an observer (in this case, on Earth). When this happens, the gravity of the star in front magnifies the light of the star behind it, acting like a lens. Should the star in front have a planet, that planet would create a "blip" during the magnification, NASA said in the statement.

The challenge, however, is pinning down how far away the closer star (and its planet) is from Earth. Microlensing tends to magnify the star behind, but usually the star in front is invisible to observers. That's why about half of the 30 or so planets found with microlensing (including a few Tatooine-like planets) are at unknown distances from Earth.

To overcome the distance problem, astronomers used the Spitzer telescope in concert with the Polish Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) Warsaw Telescope at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. OGLE routinely does microlensing investigations, but for Spitzer, this was the first time the long-running telescope had successfully used the technique to find a planet.

Quick telescope work

Prominent telescopes like Spitzer are usually fully booked with other astronomical observations. This makes it difficult to respond quickly when the astronomical community is alerted about a microlensing event, which lasts only 40 days on average. Spitzer officials, however, have worked to do these observations as early as three days after an event is announced.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new planet's microlensing event was quite long, roughly 150 days.

Spitzer orbits the sun from a position behind Earth (about 128 million miles or 207 million kilometers away from its home planet, further than the Earth-sun distance). This vast distance from its home planet means the telescope sees microlensing events occur at a slightly different time than do telescopes on Earth.

Spitzer spotted the "blip” in the magnification about 20 days before OGLE did. By comparing the delay between what Spitzer and OGLE saw, astronomers could calculate the planet's distance from Earth. Once they knew that measure, they were able to estimate the planet's mass, which is roughly half that of Jupiter.

This is the first time Spitzer found a planet using microlensing, but it comes after 22 previous attempts with OGLE and other telescopes on the ground. Astronomers forecast Spitzer will examine 120 more microlensing events this summer.

So far, microlensing has helped astronomers find 30 planets at distances as far as 25,000 light-years away from Earth. That's in addition to the more than 1,000 closer worlds discovered by the planet-hunting Kepler space telescope and ground-based observatories using other techniques. Astronomers are using the microlensing events to seek out planets in the central "bulge" of the Milky Way, a spot where stars are more densely packed and tend to cross more often.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.