Ancient Artifacts to Space Tech: History of Tools Explored in NYC Exhibit

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

NEW YORK — An exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York juxtaposes tools from throughout human history — from ancient rock tools, to the most cutting-edge instruments being used to explore outer space — and looks for the commonalities among them.

What does a 1960s spacesuit have in common with a 1.8-million-year-old "chopper" rock used by human ancestors to crush grain? What does a high-definition video display of the surface of the sun, captured 24/7 by a group of high-tech satellites, have in common with hammers and screwdrivers made from just wood and metal?

All of these items are tools. And while cutting-edge technology may seem fundamentally different from simple hand tools, the basic purpose of tools has not changed throughout human history — they serve as a means for improving our interaction with the world. The exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt museum titled "Tools," explores this concept by drawing together artifacts and items from nine Smithsonian museums and research centers, including the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. [Photos: Humanity's Space Tech Tools & Ancient Artifacts at Cooper Hewitt Museum]

Making sense of the world

"Almost everything we do involves a tool," Cara McCarty, curatorial director of the Cooper Hewitt museum and co-curator of the "Tools" exhibition, said as we walked through the third floor of the Cooper Hewitt museum.

To create the exhibit, McCarty and McQuaid borrowed items from nine Smithsonian museums and research centers. Items from the Air and Space Museum are artifacts from the National Anthropological Archives and the National Museum of the American Indian.

In the entrance to the exhibit is a collection of toolboxes. A few of the boxes contain hammers, screwdrivers, saws and and wrenches. There is also a tool kit used by astronauts aboard Skylab, the United States' first space station, adapted for a microgravity environment. There is a traveling dressing table from 1875 with tools for personal grooming; writing-tool boxes from the mid- to late 1700s that contain quill pens and ink; a sewing box; a lithotomy surgical set from the 1830's, containing instruments designed specifically for removing and crushing stones from the kidney or bladder; and finally, a MacBook Pro.

"This is our toolbox," McCarty said, pulling out her own smartphone. "We keep getting more and more tools to fill it." She later noted that people "get very personal about tools; there's an aspect of identity in them."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To cultivate a collection of unique tools for the exhibit, McCarty and her co-curator, Matilda McQuaid, head of textiles at the museum, visited different Smithsonian Institutes, and asked the people there about the tools they kept and the tools they used.

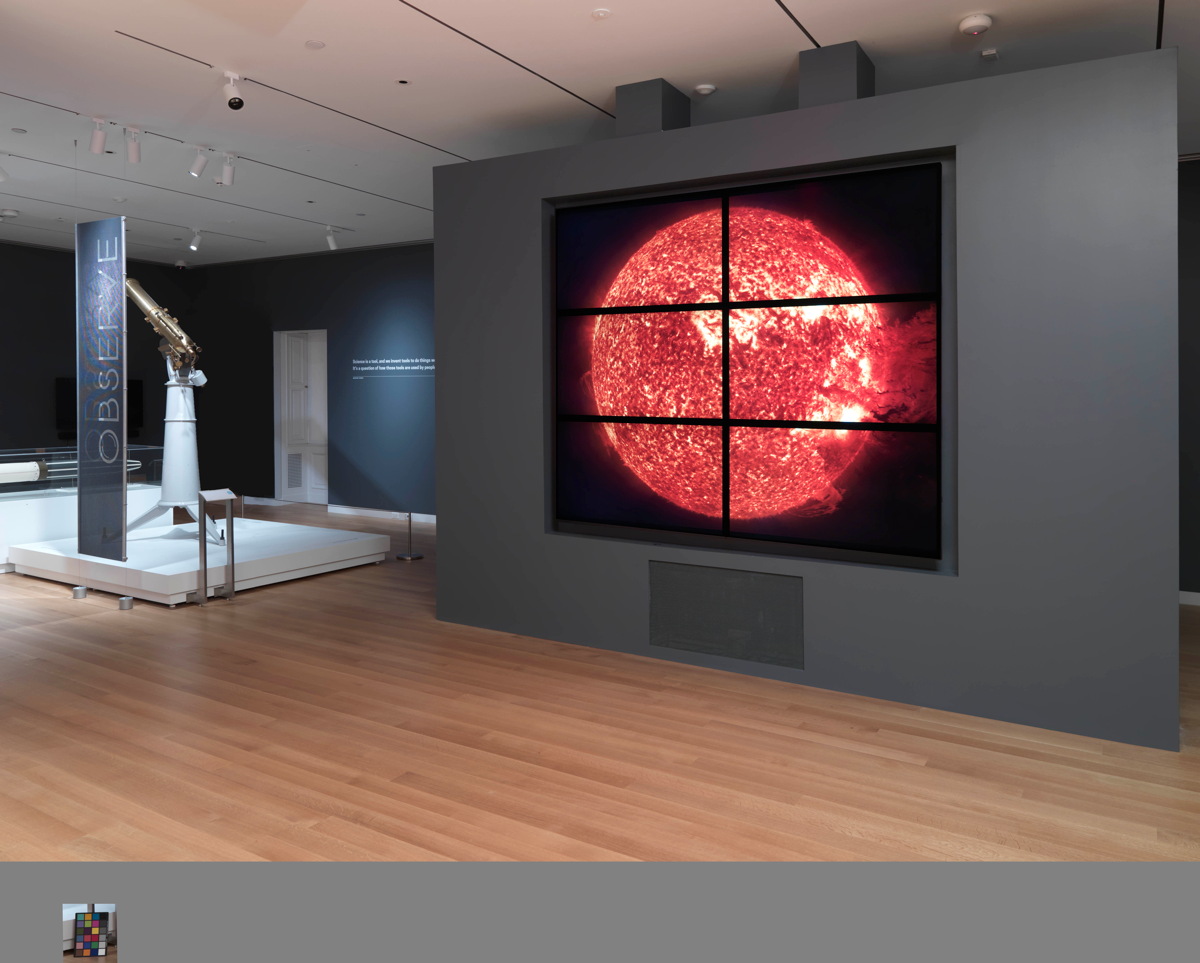

At the Smithsonian's Center for Astrophysics at Harvard, the pair found one of the most eye-catching pieces new featured in the exhibit: a wall-size display that plays continuous video footage of the sun, taken from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO).

"We came in, and we saw a professor with some students — and they were watching this live feed of the sun," McCarty said. "This is their tool for learning about the sun in real time."

The images show the sun's turbulent surface, full of dark spots and twisting magnetic-field lines.

The screens show images of the sun captured at "twice the resolution of a standard high-definition television," according to the exhibit catalog. The large display offers viewers the ability to see these incredible details without having to lose the wide view.

"This is their tool for visualizing the data," McCarthy said. "We're a culture of data; we have so much data. How do we put that data into a format so we can interpret it and use it?"

No previous generation of people has had to create tools to manage the volume of data that 21st-century humans regularly produce. But while the volume may have changed, McCarthy said the basic question is the same: "How do we make sense of it all? How do we make sense of the world as human beings?"

In the section near the sun is a map of ocean currents, made of straight and curved sticks tied together in a frame. It's from Micronesia, a country that "made some of the finest oceangoing vessels in the world," according to the exhibit catalogue. The map was a primitive GPS system — an attempt to make sense of the world.

The Purpose of Tools

The tools in the exhibit are not organized chronologically, but are instead grouped by purpose: tools to do work, to observe the world, to survive, to communicate, to measure and to make.

Many of the space-related items fall under the category of "observe." Near the display from SDO is a series of items borrowed from the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum. There is a telescope built in the United States in the 1800s to study the transit of Venus. Nearby is a replica of Explorer 1, the first U.S. Earth-orbiting satellite. Behind the solar display is a replica of the first radio astronomy satellite, Ariel 2, launched by the United Kingdom's Science and Engineering Research Council in 1964.

These space tools are relics compared to the satellites used to image the sun, but at one point in time, they were considered cutting-edge.

In the "make" category is an example of the first 3D printer built specifically for use in microgravity. One of these printers is currently undergoing tests aboard the International Space Station. Designed by NASA and a company called Made in Space, the printer must account for the pecular conditions of microgravity, such as components floating away as they are produced. A fully functioning 3D printer aboard the station would liberate astronauts from their dependence on supplies sent up from Earth.

What may differentiate many of the older tools from those of the computer age is that today's tools can often serve multiple purposes. In addition to helping astronomers view the wonders of space, for example, satellites and telescopes measure, communicate and help people do work.

In the section of the exhibition titled "Survive" is a B.F. Goodrich Mark V pressure suit from 1968. The olive-green suit was intended to give astronauts greater mobility while also keeping them alive in the harsh conditions of outer space. The final product looks like something out of a Tim Burton movie, with an accordion-style hinge on the right shoulder, and the body of the suit covered in zippers and pressure gauges.

Suits like the Mark V were originally designed to keep aircraft pilots alive when they reached high altitudes, where oxygen was scarce (this was prior to the invention of pressurized cockpits). With the dawn of the space age, B.F. Goodrich tried to transition the suit technology to work for astronauts in the vacuum of space. [Spring Space Sales: Space Artifacts and Astronaut Mementos]

Accompanying the Mark V suit is a parka made by a Yup'ik Eskimo prior to 1925. The parka is made from sinew (animal tendon), and stitched with a combination of sinew and twine. To test the impermeability, the maker would tie up the sleeves at the wrists, and fill the entire parka with water, to assure that not a drop could leak through.

"I love how design pulls in disparate ideas and brings them together, and might juxtapose things in ways that maybe they haven't been juxtaposed before," McCarty said.

The "Tools" exhibit explores the marvel of tools and what they allow us to accomplish, while also reminding us that the most cutting edge tools we have access too, will one day appear primitive. Among the vast number of items that can be considered tools, the exhibit suggests that at a basic level, tools have served the same purposes and functions for hundreds of years. They are an extension of the human body and the human mind, specially designed for navigating the world.

"Informing most tools are the limitations and desires of the human body," McCarty wrote in the exhibit catalog. "They are the first evidence of human design, going back to Paleolithic times; and today, more than ever, they are opening up worlds to us, including those we cannot yet travel to physically."

There are additional space-based items on display in the "Tools" exhibit, which is open until May 25.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter