The Hunt for Exoplanets Heats Up

Kelen Tuttle, writer and editor for the Kavli Foundation, contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

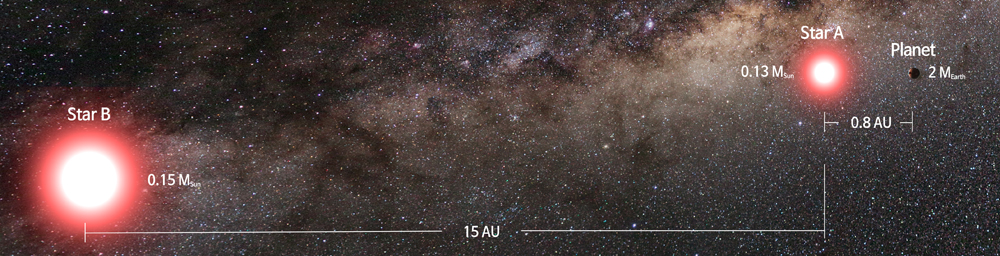

It's a time of amazing discovery in the hunt for planets in other solar systems. Over the past six months, more than 700 exoplanets have been found. It seems that each week brings the announcement of another foreign world: a rocky orb that seems much like Earth except that it's 17 times more massive; a colossal planet that orbits its star at a whopping 2,000 times the distance between Earth and our sun; an Earth-like planet in a two-sun system.

On July 9, three astrophysicists — Zachory Berta-Thompson, Bruce Macintosh and Marie-Eve Naud — came together to discuss this explosion in exoplanet discovery in a live webcast hosted by The Kavli Foundation, part of a continuing series that gives viewers a chance to ask questions of scientists at the forefront of some of the world's most exciting research. (To keep up to date on future webcasts, follow the foundation on Twitter: @KavliFoundation)

"What is really fascinating at this stage of exoplanet science is that we have many methods, and all the methods can help to find given planets — planets with certain characteristics — and bring different information," said Naud, a University of Montreal Ph.D. student who led a recent study that discovered a strange gas giant exoplanet called GU Pisces b. "When we are able to combine different methods, we are able to see so much more."

Combining planet-hunting methods has not only enabled the recent explosion in exoplanet discovery , but has also increased what can be inferred about each planet. Scientists are now able to determine an exoplanet's characteristics including its size, mass and density, as well as the chemical make-up of the planet and its atmosphere.

What's especially exciting about identifying these chemicals is that they "can tell you things like the history of the planet — how it formed," said Macintosh, a member of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology and the principal investigator for the Gemini Planet Imager. "We think we understand enough about the process that formed planets in our solar system to see that it left a chemical signature in the atmosphere of, say, Jupiter and we can try to look for that same chemical signature in the atmosphere of other planets."

All three scientists agreed that, in addition to finding and characterizing planets, there's another burning question that makes them excited to come to work each day: the hunt for planets that could support life.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I think it'll be really tough, but … thanks to the Kepler mission , we now know that the rate of occurrence of potentially habitable planets around small stars is ... more than one out of ten," said Berta-Thompson, the Torres Fellow for Exoplanetary Research at the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. "And so this does really increase our chances."

For more on the three astrophysicists' expectations for finding life on other planets, their favorite of the 1700 planets discovered so far, and the burning questions that makes it exciting from them to come to work each morning, watch the complete discussion, recorded live during a Google Hangout.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

A former contributor to Space.com, Kelen is currently the Senior Director of Creative Services for GeneDx where she acts as an in-house agency dedicated to bringing the GeneDx brand to life consistently and effectively. Prior to this position she was a freelance science writer and editor after stints as the EIC of Symmetry Magazine and six years at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, She obtained her MS in Science Journalism from Boston University after her undergraduate work in Physics and Astrophysics from Carleton College.