Incredible Technology: Giant Starshade Could Help Find an Alien Earth

Editor's Note: In this weekly series, SPACE.com explores how technology drives space exploration and discovery.

A flower-shaped spacecraft may help scientists see Earth-like alien worlds like never before.

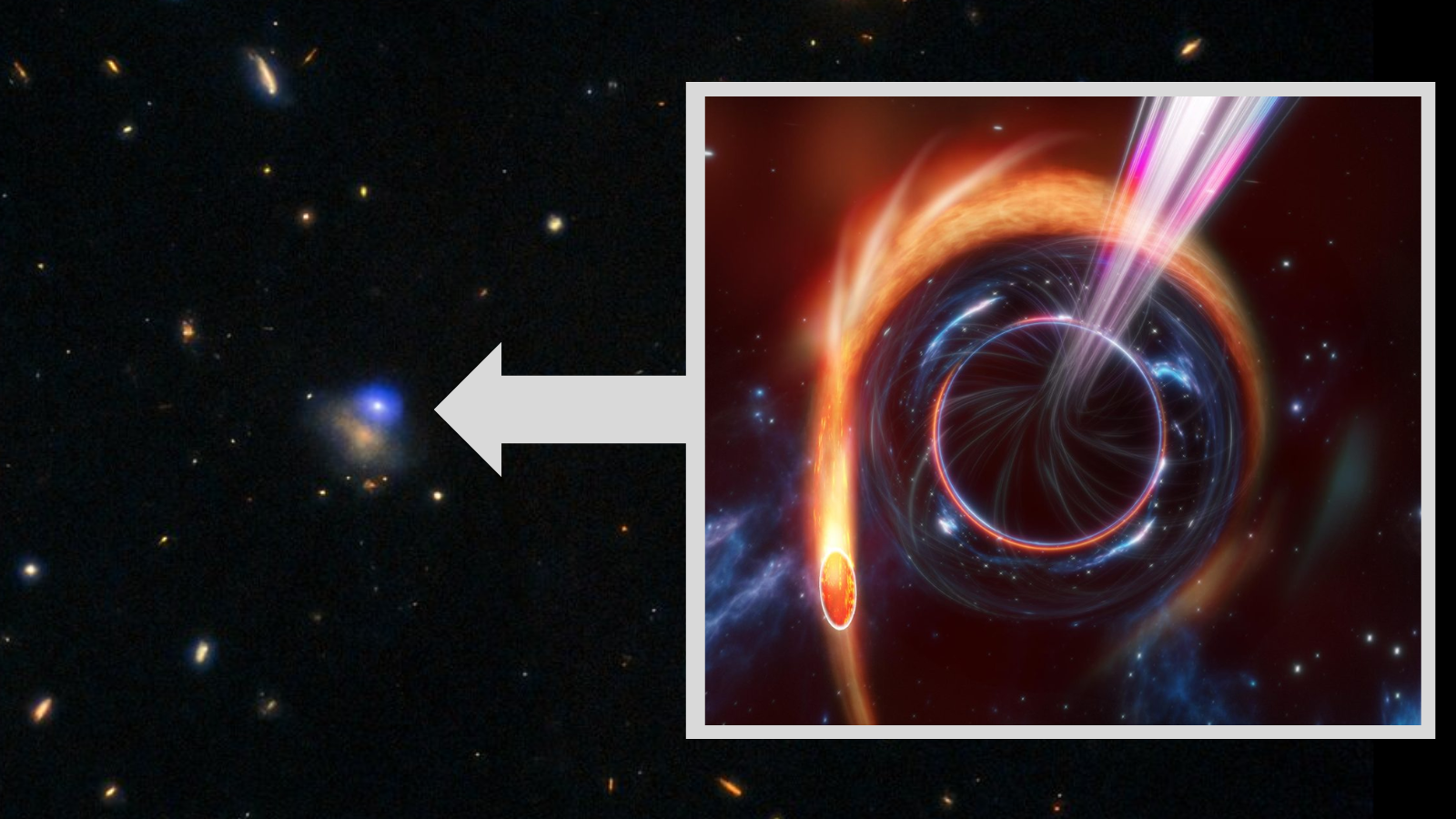

Called a "starshade," the huge, sunflower-like spacecraft would deploy to its full size in space, blocking the light of distant stars so that a space-based telescope can image exoplanets in orbit around the stars. With this technology, researchers could directly image other worlds and potentially find long sought-after Earth twins, a historically difficult task for alien planet hunters.

While still in the early phases of development, the starshade could hunt for small planets around bright, nearby stars. This would help scientists learn more about the planets and even hunt for signs of potential life by peering into the alien worlds' atmospheres. [See How the Planet-Hunting Starshade Unfolds in Space (Video Animation)]

"It's a very specialized screen in space," planetary scientist and MIT astrophysicist Sara Seager said of the starshade concept. "It blocks out the light from the star. Only the planet's light enters the telescope. This is not what we traditionally do. Traditionally, the telescope does everything. … It's the only way to find Earths with a relatively small and simple space telescope."

A small telescope in space

As it stands now, the assumed $1 billion mission would be able to target about 55 bright stars in a three-year span. Seager, the chair of NASA's science and technology definition team for the starshade project, thinks it's possible to find Earth-like planets orbiting 22 of those 55 stars targeted by the mission. [9 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One major advantage to the starshade is that astronomers won't need to couple it with a large, extremely expensive space telescope. By blocking out the light of a star before that light ever reaches the telescope, the starshade eliminates the need for a huge telescope, Seager said.

"You don't need a very fancy telescope that's highly thermally and mechanically stable," Seager told Space.com. "You can use any old space telescope. We can buy a telescope. That's what we're thinking of. … It sounds a little funny, but any telescope will do."

Engineering a starshade

Building a starshade poses a serious engineering challenge. While the telescope and starshade can launch together, the starshade will need to move out from the telescope once both robots reach space.

"[Most starshade designs] are tens of meters [in diameter] and flying tens of thousands of kilometers from the telescope," Seager said. "It's challenging. It sounds insane. The thing is, no matter how you do it, it's really difficult."

But it's also still very difficult to create a large telescope with the internal machinery used to correct for starlight, Seager added.

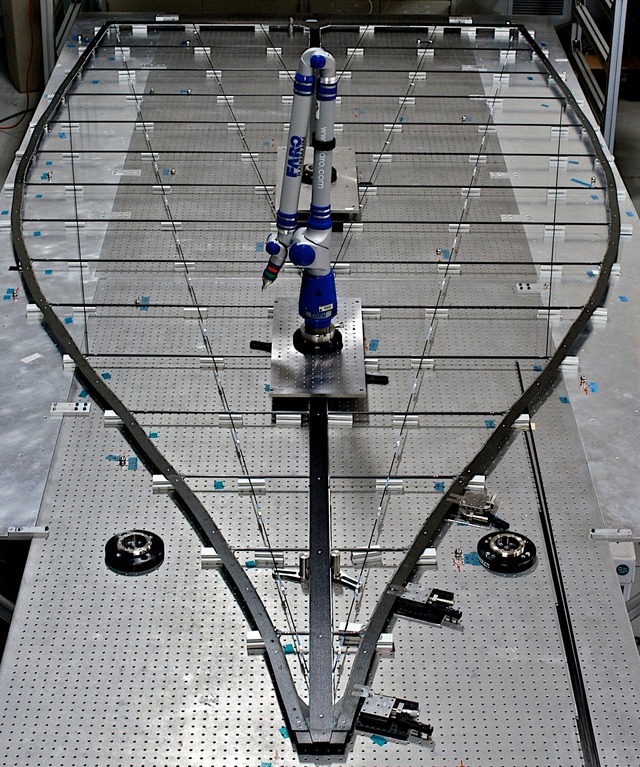

The starshade itself needs to be designed with extreme accuracy so that it can block light effectively once in space. Researchers on the ground at Princeton University in New Jersey and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California are working to test models of the starshade now.

"Our current task is figuring out how to unfurl the starshade in space so that all the petals end up in the right place, with millimeter accuracy," Princeton professor Jeremy Kasdin, the principal investigator of the starshade project, said in a statement.

Space sunflower

Once in space, the starshade unfolds and is positioned between the star and the telescope. The shade's unique shape blocks the starlight, potentially revealing exoplanets in orbit around the star that couldn't have been seen previously. With the light blocked, a telescope can directly image the planets.

"The shape of the petals, when seen from far away, creates a softer edge that causes less bending of light waves," Stuart Shaklan, lead engineer on the starshade project at JPL, said in a statement. "Less light-bending means that the starshade shadow is very dark, so the telescope can take images of the planets without being overwhelmed by starlight."

The starshade would come equipped with thrusters to maneuver into different positions to block the light of the 55 stars it will blot out through the course of the mission. Although it will take time to move the starshade into place for each target, the telescope can perform other astrophysics tasks while waiting for the next star to come into view, Seager said.

NASA's Kepler mission hunted for exoplanets until it suffered a critical failure last year. Unlike a starshade, Kepler used the transit method, recording small dips in a star's light as a planet passed in front of it, to find other worlds.

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), scheduled for launch in 2017, also uses the transit method to find exoplanets, and this mission is expected to target other stars in a wider swath of sky. TESS probably won't find Earth twins, but it will be able to see rocky planets around stars that are smaller than the sun, Seager said.

With the starshade mission, scientists could potentially find Earth-twins orbiting sun-like stars.

"These Kepler planets are too far away for us to directly study atmospheres of small planets," Seager said. "We mostly decided now that transits won't work for true Earth analogues. For Earth and sun-like stars, you just have to think of the size of the atmosphere — it's like a ring compared to the sun. It's tiny. We don't think we can do [image] that, not to mention that transits are rare. One in 200 Earths will transit, so finding one around a bright enough star may never happen. … Direct imaging is inevitable."

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.