Canadian Astronomers Battle Funding Cuts and Perceptions

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

MONTREAL, Quebec — Flashing a picture of the star HR 8799 and its four alien planets on a big screen, astronomer Andrew Cumming smiled. "This is the most amazing picture in exoplanet science!" he exclaimed.

Cumming described how astronomers tracked minute variations in the system to study these alien worlds: "Over four years, we started to see one planet moving in its orbit," he told delegates of the Canadian Science Writers' Association during a talk at McGill University here June 7.

Cumming is a theoretical astrophysicist at the university who focuses on compact objects, particularly super-dense neutron stars, as well as exoplanets. These days, though, his attention is somewhat distracted. There are changes afoot in Canadian astronomy funding.

Last year, at least one of the Canadian Space Agency's astronomy programs came close to the chopping block amid government cost-cutting, he said. Even today, many researchers are nervous. [Photo Tour: Canadian Space Agency Headquarters]

"One always wants more invested in the field you're working in," Cumming told SPACE.com, echoing concerns of several astronomers at the conference.

Research vs. business

Canadian astronomy receives funding principally from three government departments: the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, and the National Research Council (not to be confused with the U.S. entity of the same name.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Money is tight these days in the Canadian government, however. Officials with the ruling Conservative party have said they are conscious of the federal budget deficit and must make cuts. Critics, however, argue that fundamental research is coming under attack.

In May, Tory officials said they would change the NRC's mandate to "invest in large-scale research projects that are directed by and for Canadian business."

In response, the Canadian Association of University Teachers called the change "short-sighted, misguided and unbalanced" because it would jeopardize the resources of universities that rely on NRC labs to perform research. Other researchers cried foul in the media.

Meanwhile, the CSA's budget for space exploration, which includes astronomy, will fall in coming years, according to the latest figures released by the agency in mid-2012.

From $148.2 million ($151 million in Canadian dollars) in 2011-12, funds will decrease 40 percent to $91.2 million ($93 million CDN) in 2014-15.

One initiative called the "space science enhancement program" (SSEP) was nearly canceled last year, Cumming said. The CSA website now has a notice saying it is suspended. (Agency officials did not respond to requests for comment.)

The top goal of SSEP was, according to the CSA website, "to maximize the scientific return to Canada by providing funding to space science projects and activities in the areas of initial instrument studies, data analysis and other space science-related academic studies."

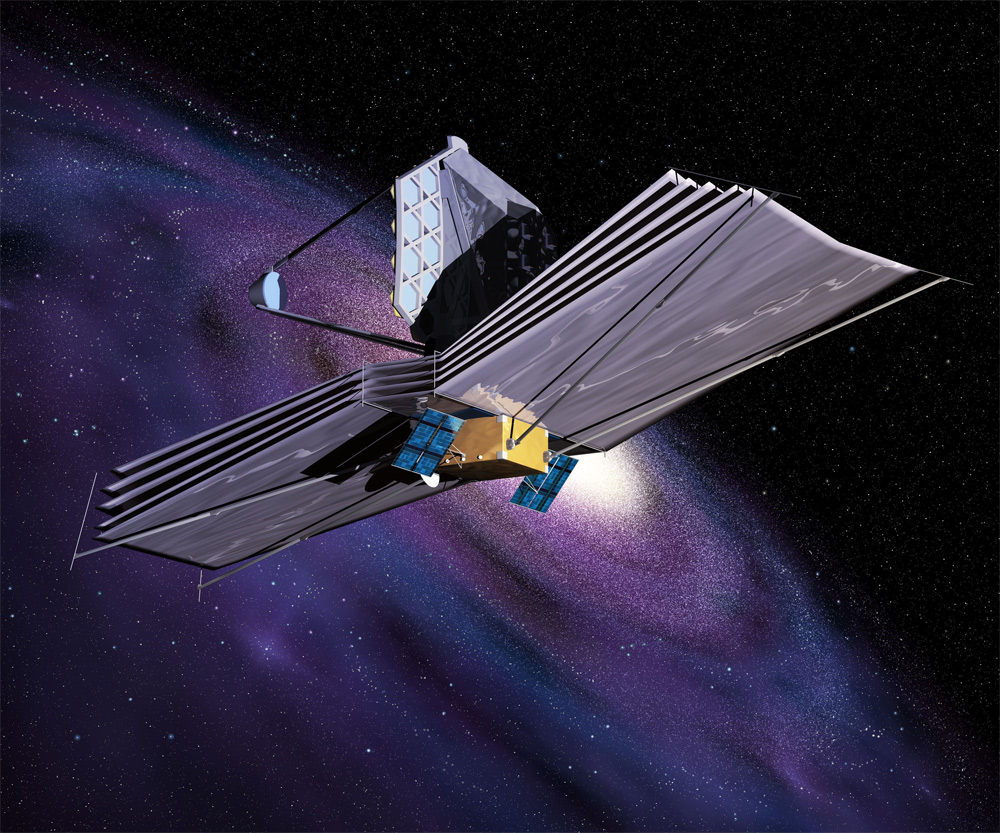

Cumming added that with the James Webb Space Telescope taking $143.6 million ($146 million CDN) from Canadian space funds over 10 years, he worried the slices of research left would starve to death. The over-budget successor telescope to Hubble is expected to launch in 2018, costing more than $8 billion, most of which is coming from NASA.

Funding fundamental science

René Doyon, a University of Montreal researcher who is principal investigator of a near-infrared spectrograph instrument on James Webb, said he sees the telescope as a worthy investment for Canada.

Among the many scientific discoveries it should enable, astronomers are hoping it reveals the atmospheres of alien planets. By contributing 5 percent of the total cost of the observatory, Canada gains an according amount of telescope time for its participating astronomers. "It will open up new capabilities," Doyon said.

"We don't have examples of commercialized technology that come out of [astronomy]," Doyon added, "but to answer these big questions — where are we coming from, is there life outside of the solar system — involves pushing technology to its limit."

Although astronomy may not lead to direct technological spinoffs, McGill astronomer Vicky Kaspi (who co-authored a paper concerning an "anti-glitch" magnetar star published last month in the journal Nature) said she has seen applications in her lifetime from fundamental astronomy research.

"A lot of X-ray astronomy does beautiful images of supernova remnants and pulsar nebula," Kaspi said. "One of my Ph.D. students is in medical imaging, and [is] bringing the tools that she learned in manipulating X-ray images ... to bear on imaging tumors or different parts of the body."

"When you take a challenge, as a technological challenge, there are very interesting ways that it can be used that you wouldn't expect," Kaspi added. "A hundred years ago, if you wanted to improve the lighting in your house, would you spend money developing better candles, or would you want to put money into crazy electricity research? At the time it seemed pretty wacky, but in hindsight, it would have been the better bet."

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.