Russian Meteor Fallout: Boosting Asteroid Search May Not Help, Scientist Says

Spending more money on asteroid and meteor detection techniques won't necessarily make the planet safer, according to a planetary scientist.

Alexander Deutsch, a professor of planetology at the University of Münster in Germany, explained that the relatively small meteor that exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia, in February would not have been detected using technologies available around the world today.

"The problem is that even if they use more of these highly sophisticated observatories, they will not find very small projectiles, but on the other hand, the small projectiles are not very dangerous, and the opinion is that the larger ones or at least most of the larger ones are now known," Deutsch said during a news conference today (April 9) at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly in Vienna. "I don't think more money will produce more data."

This idea is contrary to what many scientists, lawmakers and public officials have been saying since the Feb. 15 explosion of the 56-to-66-foot meteor (17 to 20 meters) space rock over Russia's Ural Mountains. [See photos of the Russian meteor explosion]

The Russian fireball's blast injured more than 1,000 people, and sparked a series of congressional hearings on asteroid detection in the United States to assess the possible threats posed by asteroids and meteors.

NASA also estimates that scientists and amateur astronomers working with the space agency have located and tracked the orbits of 90 percent of the largest near-Earth asteroids that could create a global crisis if the space rocks were to impact the planet.

Although the asteroid released the equivalent of 470 kilotons of TNT (30 to 40 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped by the United States on the Japanese city of Hiroshima during World War II), the 10,000-metric-ton meteor exploded high enough to shelter those on the ground from the brunt of its impact.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"What you see now is it doesn't matter if it's Chelyabinsk or London," Deutsch said. "If you have, let's say, good windows and solid structure and [the meteor] exploding very high, then the damage is rather small."

Deutsch also pointed out that these events are somewhat rare. Scientists have suggested that a meteor like the one that fell through the atmosphere over Chelyabinsk is expected to happen only once every 50 to 100 years. Before this year, the last meteor that produced such a blast fell over Siberia in 1908, flattening 825 square miles (2,137 square km) of forest.

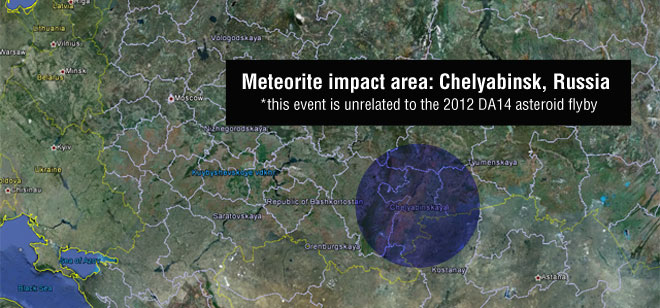

The Russian meteor exploded just before another space rock flew harmlessly past the Earth. Asteroid 2012 DA14 — a 130-foot (40 m) rock — gave the Earth a close shave in astronomical terms, missing the planet's surface by 17,200 miles (27,000 km). The two space rocks, however, were cosmically unrelated.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.