Landsat: A guide to the Earth observation satellite fleet

Landsat has given us a new view of Earth in more ways than one.

- History of the Landsat program

- Landsat 1 as a successful testbed

- Landsat 2 and agriculture applications

- Landsat 3 and privatization

- Landsat 4 and EOSAT

- Landsat 5 and a Guinness World Record

- Landsat 6's failed launch

- Landsat 7 and free imagery

- Landsat 8's increased resolution

- Landsat 9 detects minute surface change

- Additional resources:

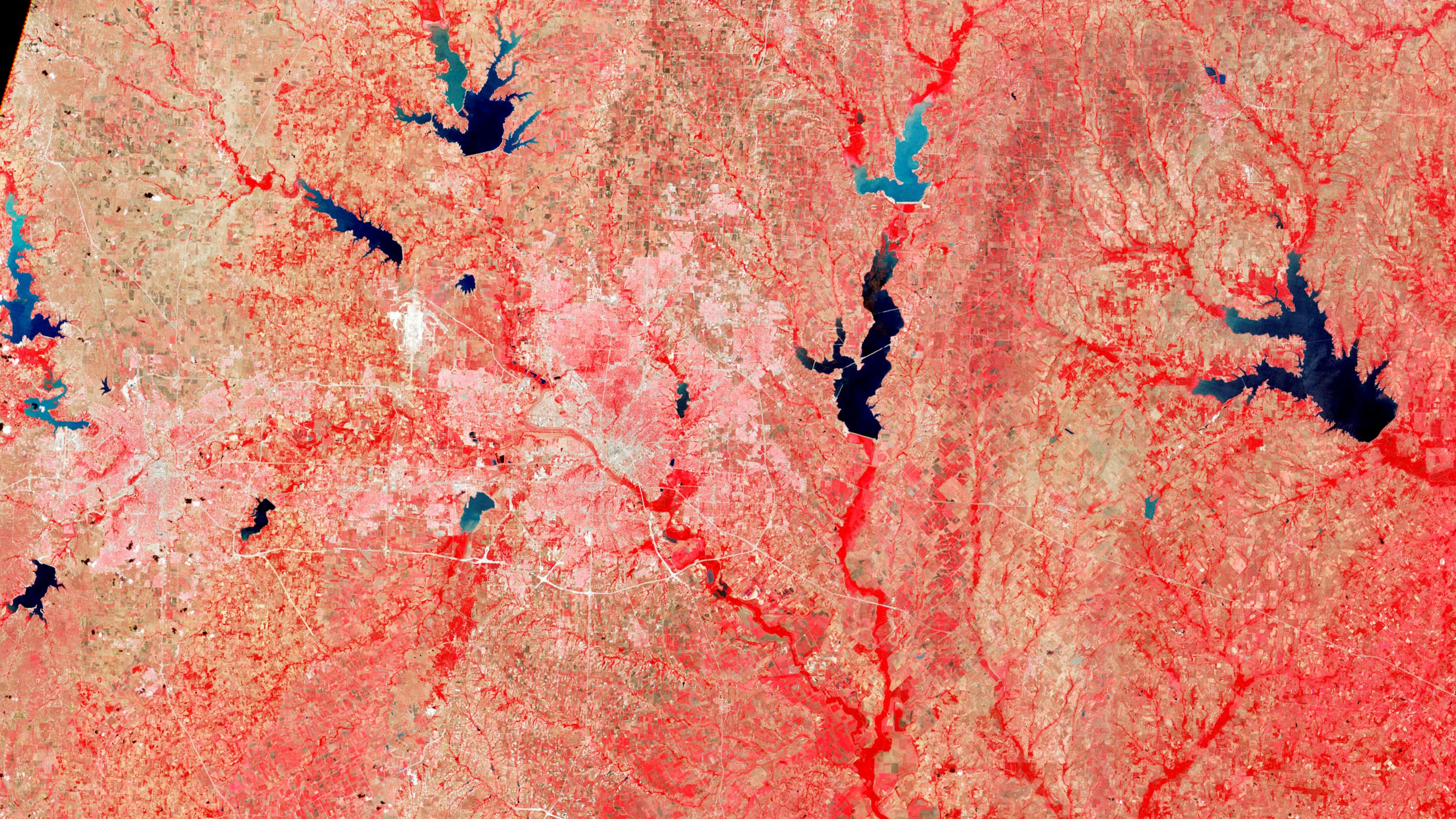

Landsat is an eagled-eyed satellite fleet that's kept a watchful eye on Earth since 1972. According to NASA, it is the "longest continuous space-based record of Earth's land in existence." The program takes images of the Earth at a range that allows scientists to see large-scale changes in the landscape, including those changes induced by human-driven climate change.

Landsat 9, the most recent of the series, launched in September 2021 and as late as 2019, researchers have said the program's consistent, multi-decadal record is a boon to science. "International programs and conventions … are empowered by access to systematically collected and calibrated data with expected future continuity further contributing to the existing multi-decadal record," wrote one scientific analysis of the Landsat program, in place since 1972.

Over the decades, Landsat satellites have tracked urban sprawl, monitored the effects of climate change, and characterized deforestation's effects on the surrounding landscape. The program is jointly run by NASA and the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and as such, much of the dataset is available for free. LandsatLook is one online tool available that allows you to seek recent information by address or place name, and to track changes in different light wavelengths.

Related: Celebrate 50 years of Landsat with these stunning images (gallery)

History of the Landsat program

The literal moonshot to map the moon's surface in the 1960s ahead of human landings inspired the Landsat program's effort to provide high-quality images of the Earth, according to NASA. Scientific funding was at a high as it was linked to national goals such as winning the so-called space race with another space superpower, the Soviet Union.

Images of the Earth were by no means new in the 1960s. The first image above the Kármán line was obtained in 1946 using a V-2 missile launched from the White Sands Missile Range, according to Air&Space Smithsonian. The first-ever Earth image from a satellite was obtained in 1959 from Explorer 6. But what was lacking was consistency. Scientists wanted a large-scale satellite series, each with a similar resolution and a similar set of orbits to best map changes to the Earth's surface.

By 1965, such a program seemed feasible as Mercury and Gemini astronauts had taken many pictures of Earth since human missions began four years before, NASA said. Then-director of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), William Pecora, said a remote sensing program would be useful to learn about the geological resources of Earth, extending applications of satellites beyond weather forecasting, and served as an advocate for his team in conversations with higher levels of government.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It wasn't an easy sell. NASA stated the Bureau of Budget and other government departments argued such satellites were unnecessary because high-altitude aircraft could obtain imagery at a lower cost. The Department of Defense also worried that providing open data about our planet would have immense security implications at the height of the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

NASA had constraint issues of its own, as efforts to put people on the moon at the end of 1969 (which succeeded with Apollo 11) slowed the development of Landsat, according to Sam Goward, a researcher with the Landsat Legacy Project in 2010 that sought to collect technical information about the program. However, a long-brewing joint effort about Earth satellites between the Department of the Interior and the USGS, of which USGS was a part, came to fruition in 1966.

USGS penned a memo to Stewart Udall, then DOI secretary, advocating for an Earth Resources Observation Satellite (EROS) series, the predecessor to Landsat. Goward said agencies within NASA and DOD, along with U.S. President Lyndon Johnson, were reportedly unhappy with the decision as the EROS program would be a competitor for collecting Earth science information. Nevertheless, NASA developed the Earth Resources Technology Satellite (ERTS) in 1967. ERTS-1 launched on July 23, 1972 and was renamed Landsat 1 in 1975.

Landsat 1 as a successful testbed

Landsat 1 — then known as the Earth Resources Technology Satellite — launched successfully on July 23, 1972. It outlasted design expectations by five years before being decommissioned on Jan. 6, 1978, according to USGS.

The satellite imaged roughly 75% of the Earth's surface using two instruments: a return beam vidicon (somewhat similar to a television camera) and a multi-spectral scanner. "The RBV was supposed to be the prime instrument, but the MSS data was demonstrably superior," USGS wrote.

Landsat 1's contributions included changing country boundaries (due to more precise mapping from space) and rediscovering new islands, including one in Canada (north of Newfoundland and Labrador) named "Landsat Island."

Landsat 2 and agriculture applications

Landsat 2 launched on Jan. 22, 1975, with identical instruments to Landsat 1. (Like its sibling, this satellite launched under the Earth Resource Technology Satellite naming convention, as ERTS-B, and was retrospectively renamed Landsat 2.) Landsat 2 worked for seven years in space, outlasting expectations sevenfold, before finishing service after Feb. 28, 1972, due to yaw problems, according to USGS.

Landsat 2 not only continued the program of continuously monitoring the Earth's surface but participated in a cooperative agriculture experiment known as The Large Area Crop Inventory Experiment (LACIE). The program, launched after a major harvest failure in the Soviet Union forced the country to purchase U.S. wheat in 1972, provided unprecedented year-by-year predictions on agriculture yields. A successor program launched in 1979, called Project Agriculture and Resources Inventory Surveys Through Aerospace Remote Sensing (AgRISTARS), included monitoring of corn and soybeans, according to USGS.

The agriculture programs are a predecessor of today's enhanced satellite imagery, which examines crops in multiple wavelengths using digital image processing to estimate yields, USGS added. The agency has also cited these programs as valuable for testing out food security initiatives.

Landsat 3 and privatization

Landsat 3 launched to orbit on March 5, 1978, with improvements over the past two satellites in the series. Its return beam vidicon (RBV) had a resolution of 131 feet (40 meters), double that of Landsats 1 and 2. Engineers also added a thermal, infrared band to the multispectral scanner system (MSS), although this band, unfortunately, failed not long after launch, according to USGS. It was removed from service in 1983.

The year 1983 also coincided with a program change within Landsat operations, which were transferred from USGS to NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). USGS, however, maintained the archive of data. "This was the first step in a long process of commercialization," USGS wrote.

Making this data commercial resulted from years of political and economic pressures, alongside Landsat's ongoing success, according to NASA. The presidential directive NSC-54 was signed during Landsat 3's early operations on Nov. 16, 1979, making NOAA responsible for "civil operational land remote sensing activities" and NASA responsible for research and development.

The commercialization process was long and complex, according to a chapter on Landsat in a 1998 NASA history volume, "From Engineering Science to Big Science," edited by Pamela Mack.

"President Jimmy Carter made a priority of reducing the size of the federal government, and his staff identified Earth resources satellites as one of the best candidates for transfer of a government function to private industry," the chapter noted.

However, when Carter asked his administration to approach the private industry in 1978, demand was not there and there was conflict within the U.S. government about how to manage Landsat operations. These and various other issues pushed back the privatization of the system until 1983, under the Reagan administration.

Landsat 4 and EOSAT

Landsat 4 launched on July 16, 1982, and was functional until 1993. In addition to the multispectral scanner (MSS), it carried a more advanced imaging sensor called the thematic mapper that aimed to better image natural disasters from space, according to USGS.

Under the ongoing privatization of Landsat, the Earth Observation Satellite Company (EOSAT) took over operations in 1984 from NASA. The company was a joint venture between Hughes and RCA, according to Mack; during its early years, EOSAT received a small government subsidy along with no guaranteed purchases by the federal government for data services, contributing to an uncertain future.

Landsat 4 had a lower orbit than its predecessors, but a higher field of view to maintain the same "swath width" (or imaging width) of 115 miles or 185 kilometers. However, the swathing pattern changed due to the lower altitude, USGS stated.

Landsat 5 and a Guinness World Record

Landsat 5 launched on March 1, 1984. Like Landsat 4, the satellite carried a multispectral scanner (MSS) and thematic mapper and was expected to last three years. The satellite exceeded lifetime expectations tenfold and set a Guinness World Record for "longest operating Earth observation satellite" for nearly 30 years of operations ending June 5, 2013, according to USGS.

However, Landsat 5 almost didn't make its record due to complexities with EOSAT and the associated Land Remote Sensing Commercialization Act of 1984 meant to sell Landsat data commercially, NASA stated. The law restricted EOSAT's commercial practices; with demand artificially reduced, the company was forced to raise prices by 600%.

At first, Landsat had a monopoly on satellite data of this type, which allowed a limited number of users to participate if they could afford to do so; others needed to use free and lower-resolution data from weather satellites, NASA added. But Landsat's competitive advantage evaporated in 1986 when a French satellite launched with similar capabilities to the U.S. series. (The satellite was called SPOT, a French acronym for "System for Earth Observation.")

With fewer buyers for data, Landsat 4 and 5 both "languished' (in NASA's words) by reducing imaging observations, calibrations and other activities that induced expenses. By 1989, shrinking operational budgets, lackluster user interest and associated reductions in government commitment had diminished so much that NOAA requested EOSAT turn off the two now-elderly satellites.

"The program was only saved by a strong protest from Congress and foreign and domestic data users, and an intervention by the vice-president," NASA wrote. This surge of interest prompted Congress to pass the Land Remote Sensing Policy Act of 1992. Landsat 7 (covered below) was launched under government ownership and two years after that launch, the U.S. government assumed operational responsibility for Landsat 4 and Landsat 5. More affordable USGS pricing for their imagery was established in 2001.

Landsat 6's failed launch

Landsat 6 is the only satellite of the series that did not achieve operations. Following the launch on Oct. 5, 1993, the Titan II launching rocket had a problem during stage separation. A ruptured hydrazine fuel chamber stopped fuel from reaching a kick motor required to place the satellite in its operational orbit, according to NASA.

Landsat 6 was supposed to use an enhanced thematic mapper in orbit for the first time, picking up information in eight spectral bands as opposed to the seven available in Landsats 4 and 5.

Operators were lucky, NASA noted, not to experience a gap in Landsat data given the circumstances of 1993: the existing satellites were old and Landsat 7's planning was in a very early phase. Landsat 5's unexpectedly long lifetime allowed the program to continue functioning through this transition.

Landsat 7 and free imagery

Landsat 7 launched on April 15, 1999, nearly six years after Landsat 6's failure. An enhanced thematic mapper plus (ETM+) sensor was launched with even more spectral bands and spatial mapping of 50 feet (15 meters). A thermal infrared channel on the ETM+ improved fourfold upon resolution from previous Landsat thematic mappers, according to USGS.

While Landsat 7 has been grappling with a scan line corrector failure since 2003 that creates data gaps, it remains operational as of mid-2022 and may serve as a testbed for orbital refueling before it is decommissioned.

As for its imagery: Changes in U.S. policy, likely sparked by the rise of free satellite imagery available online in the early 2000s, allowed USGS to make all Landsat 7 data free to the public in October 2008. All Landsat data in the USGS archive became free in December 2009, according to NASA.

Landsat 8's increased resolution

Landsat 8 launched on Feb. 11, 2013, with two science instruments: an operational land imager (OLI) and a thermal infrared sensor (TIRS), according to NASA. Spatial resolution varies between 50 feet (15 meters) in panchromatic, 98 feet (30 meters) in visible, near-infrared and short-wave infrared, and 328 feet (100 meters) in thermal.

As of mid-2022, the satellite is still operating well at nearly double its expected five-year design lifetime.

Landsat 9 detects minute surface change

Landsat 9 launched on Sept. 27, 2021, to replace the aging Landsat 7 satellite and work with Landsat 8. The satellite has scientific instruments — the Operational Land Imager 2 (OLI-2) and the Thermal Infrared Sensor 2 (TIRS-2) — together aiming to detect minute surface changes through analysis of multiple light wavelengths.

Around launch time, program officials said the new satellite would not only maintain Landsat's continuity but extend it. "Landsat tells us about the Earth's vegetation, land use, coastlines and surface water, just to name a few," Karen St. Germain, head of NASA's Earth Science Division, said in a prelaunch briefing. "When combined with other Earth science missions, that can tell us what is happening and also why."

Like its predecessors, Landsat 9 has a five-year design lifetime but may exceed it. USGS and NASA have together been working on concepts for a Landsat 10 satellite, but have no official launch time yet on their respective websites.

Additional resources:

If you want to get your hands on some stunning and educational Landsat posters and games, NASA Landsat Science has got you covered. Put your observational skills to the test with Landsat Detective and see whether you can identify what you're looking at in a Landsat image. Take a deep dive into Landsat data with EarthExplorer and LandsatLook and learn how to use and process Landsat data with these resources from NASA.

Bibliography

Mack, Pamela E. (1998). "Landsat and the Rise of Earth Resources Monitoring." In From Engineering Science to Big Science: The NACA and NASA Collier Trophy Research Project Winners. https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4219/Chapter10.html

NASA. (2021, Dec. 9.) "Landsat." https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/landsat/main/index.html

NASA. (2022.) "Landsat Science." https://landsat.gsfc.nasa.gov/

U.S. Geological Survey. (2022.) "EarthExplorer." https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/

U.S. Geological Survey. (2022.) "Landsat Missions." https://www.usgs.gov/landsat-missions

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.