Voyager 1 Probe's 35-Year Trek to Interstellar Space Almost Never Was

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

NASA's Voyager 1 probe is streaking toward interstellar space these days, but the most far-flung man-made object in the solar system almost got stuck in Earth orbit after launching 35 years ago today (Sept. 5).

Voyager 1's Titan-Centaur rocket came within 3.5 seconds of running out of fuel when it carried the spacecraft aloft on Sept. 5, 1977, mission officials said today during a celebration of the launch's 35th anniversary at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif.

"Voyager 1 almost didn't make it 35 years ago," said Charley Kohlhase, former manager of Voyager's mission planning office. "We're here celebrating the 35 years of Voyager 1, but it was close."

A close call

The problem, Kohlhase explained, lay in an incorrect mixture ratio between fuel and oxidizer in the Titan's liquid upper stage. That made things difficult for the Centaur, which took over after the Titan was done firing. [Photos from NASA's Far-Flung Voyager Probes]

"The Centaur spent 1,200 extra pounds of fuel to get into parking orbit that it should not have normally needed to do," Kohlhase said.

During the launch, he and others on the mission team anxiously awaited word about whether the Centaur would have enough fuel to send Voyager 1 on its way toward Jupiter, Saturn and, ultimately, the solar system's edge.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It did, finally, but there were only three and a half seconds of propellant left in the Centaur tanks," Kohlhase said.

Knocking on the solar system's edge

Voyager 1 blasted off 16 days after its twin, Voyager 2. The two spacecraft were sent on a "grand tour" of the solar system's gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune), taking advantage of a favorable alignment of the outer planets that comes along once every 176 years.

Voyager 1 studied the Jupiter and Saturn systems, while Voyager 2 managed to investigate all four big outer planets. Then both probes just kept on going, speeding toward the edge of the solar system on what scientists call the Voyager Interstellar Mission.

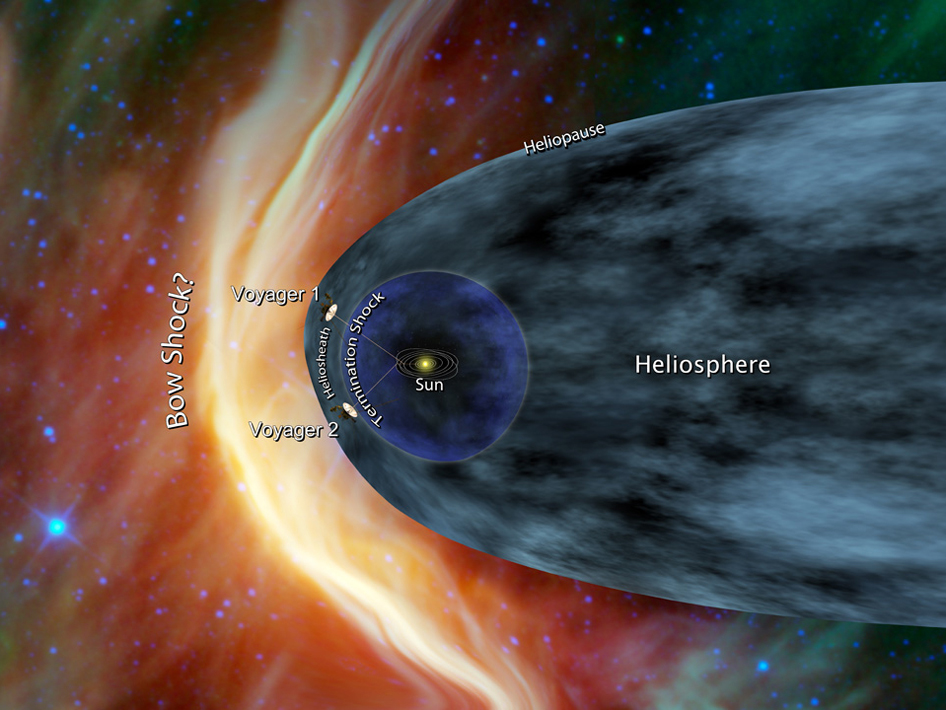

Both spacecraft are still active today. They're currently flying through a turbulent region of space called the heliosheath, where the solar wind slows as it begins to run into gas and dust from the interstellar medium.

Voyager 1 is about 11.3 billion miles (18.2 billion kilometers) from the sun at present, while Voyager 2 is lagging slightly behind — and on a different trajectory — at 9.3 billion miles (14.9 billion km) from our star.

Voyager 1 has been encountering new and strange conditions over the past several months, leading mission scientists to speculate that the probe's departure from the solar system might be imminent.

However, a new analysis of Voyager 1 data suggests that the spacecraft may not be quite as close to interstellar space as researchers had thought. Still, Voyager 1 is likely to leave the solar system within the next year, the study's lead author said.

Whenever Voyager 1 pops free, it will be a big moment for humanity — the first time our robotic reach extends beyond our own cosmic neighborhood.

"Happy birthday, Voyager," mission chief scientist Ed Stone, of Caltech in Pasadena, said in another celebration event at JPL on Tuesday (Sept. 4). "The journey continues."

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.