Gravity Waves Give Twin Stars Speed Boost, Scientists Say

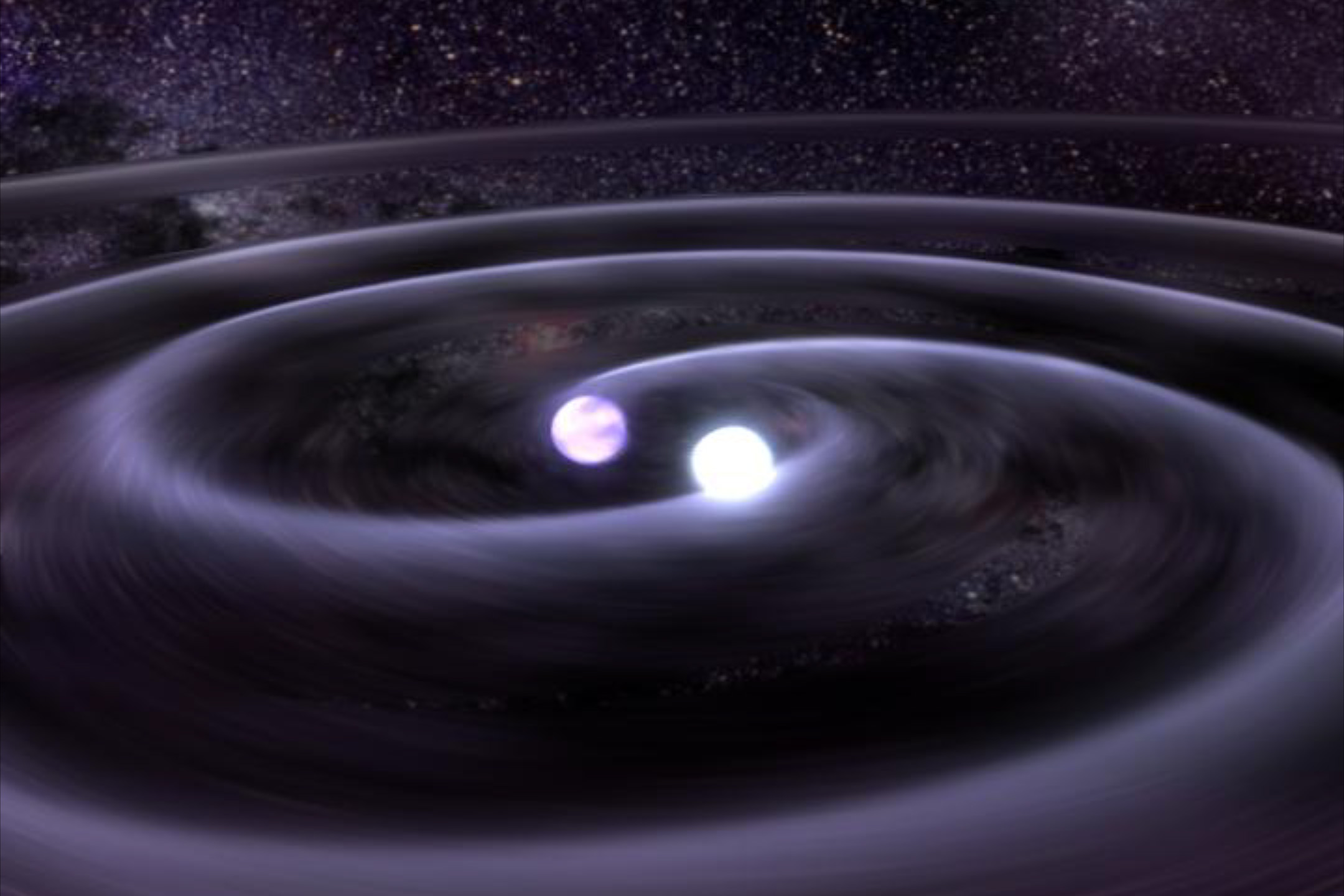

Two stars circling each other are speeding up in a tell-tale way that scientists attribute to gravitational waves: ripples in the very fabric of space and time.

The stars are dense objects called white dwarfs, which are so close together they take less than 13 minutes to orbit each other. The two white dwarfs, remnants of stars that used to be as big as our sun, are only spread apart by one-third of the distance between the Earth and the moon.

In observing this system, astronomers have made the first measurements in optical light of motions that must be caused by gravitational waves, they said.

"This result marks one of the cleanest and strongest detections of the effect of gravitational waves," astronomer Warren Brown of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory said in a statement. [8 Baffling Astronomy Mysteries]

Gravitational waves are predicted by Einstein's general theory of relativity, which posits that gravity warps space and time, causing objects traveling through it to follow a curved path. White dwarfs, being so dense, are thought to create such waves of gravity if they orbit around each other so closely. These waves would carry energy away from the system, causing the stars to crowd closer together and speed up in their orbital motion.

When astronomers first observed this system, designated SDSS J065133.338+284423.37 (J0651 for short), the stars appeared to eclipse each other, or overlap, slightly less often.

"Compared to April 2011, when we discovered this object, the eclipses now happen six seconds sooner than expected," said research team member Mukremin Kilic of the University of Oklahoma.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This quickening of motion is just what's expected if gravitational waves are being produced.

Such waves have never been detected directly, though a previous observation of a binary system composed of two dense stellar remnants (a pulsar and a neutron star) in radio light observed a similar quickening of their orbital motion. That observation, by Russell Hulse and Joseph Taylor, was awarded the 1993 Nobel Prize for providing the first indication of gravitational waves.

A ground-based experiment called LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory) could be the first to detect these space-time ripples directly when an upgraded version is complete in the next few years.

As for the two white dwarfs in J0651, scientists predict they will continue to orbit each other faster and faster in the future, with eclipses occurring more than 20 seconds sooner in April 2013 than they did in April 2011. Each year, about 0.25 milliseconds is shaved from the total orbital period of the stars.

After about 2 million years, the white dwarfs will come so close together they merge into one.

"Every six minutes the stars in J0651 eclipse each other as seen from Earth, which makes for an unparalleled and accurate clock some 3,000 light-years away," said study lead author J.J. Hermes, a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin.

The new measurements were made using more than 200 hours of observations from telescopes in Texas, Hawaii, New Mexico, and Spain's Canary Islands.

The researchers will report their findings in an upcoming issue of the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.