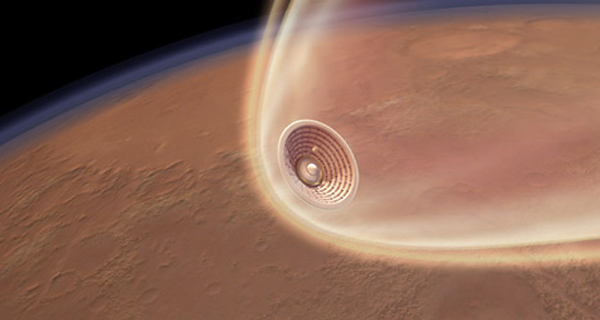

Inflatable Heat Shields Could One Day Land Astronauts on Mars

NASA successfully tested an inflatable heat shield prototype Monday (July 23), a technology that could one day be used for future space exploration missions, including landing humans on Mars, its builders say.

The Inflatable Re-entry Vehicle Experiment 3, or IRVE-3, was conducted at NASA's Wallops Flight Facility on Wallops Island, Va. During the test flight, a small capsule was launched atop a suborbital rocket, and an inflatable heat shield was deployed in space before it plummeted back through Earth's atmosphere at hypersonic speeds to splash down in the Atlantic Ocean.

The demonstration flight helps pave the way for new re-entry systems on future spacecraft, said Neil Cheatwood, IRVE-3 principal investigator at NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Va.

"As far as the applicability of the technology, [we were] originally motivated to do this to allow us to potentially land more masses at Mars," Cheatwood said in a press briefing after Monday's successful test flight. "Mars is a very challenging destination. It has a very thin atmosphere — too much of an atmosphere to ignore, but not enough for us to do the things we would at other planets. That was our motivation about nine years ago when we started doing this stuff." [Photos: NASA's Inflatable Heat Shield for Spaceships]

Since the inflatable heat shield is designed to withstand hypersonic speeds and extreme temperatures, the IRVE-3 technology could give mission managers more options for where to land future spacecraft or rovers on Mar, such as touching down at higher latitudes on the Red Planet.

"We want to go to higher latitudes at that mass, or use this technology for larger payloads, such as humans," Cheatwood explained.

The heat shield technology could also be used to tackle the issue of "garbage" on the International Space Station, Cheatwood said. Robotic spacecraft that are sent to deliver fresh supplies, food and experiments to the orbiting outpost could then be re-packed with unwanted materials to return to Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"When we send up re-supply [spacecraft] to the station, there's no portable on-demand storage up there," Cheatwood said. "When they bring up 'x' number of cubic feet of stuff, we need to get rid of that much as well."

With future tests planned to improve the heat shield technology, the IRVE-3 team has been involved in preliminary discussions with commercial companies about possible uses for these inflatable systems.

"Applications include potentially recovering launch vehicle assets," Cheatwood said. "We have had conversations with more than one commercial venture about whether this could help them."

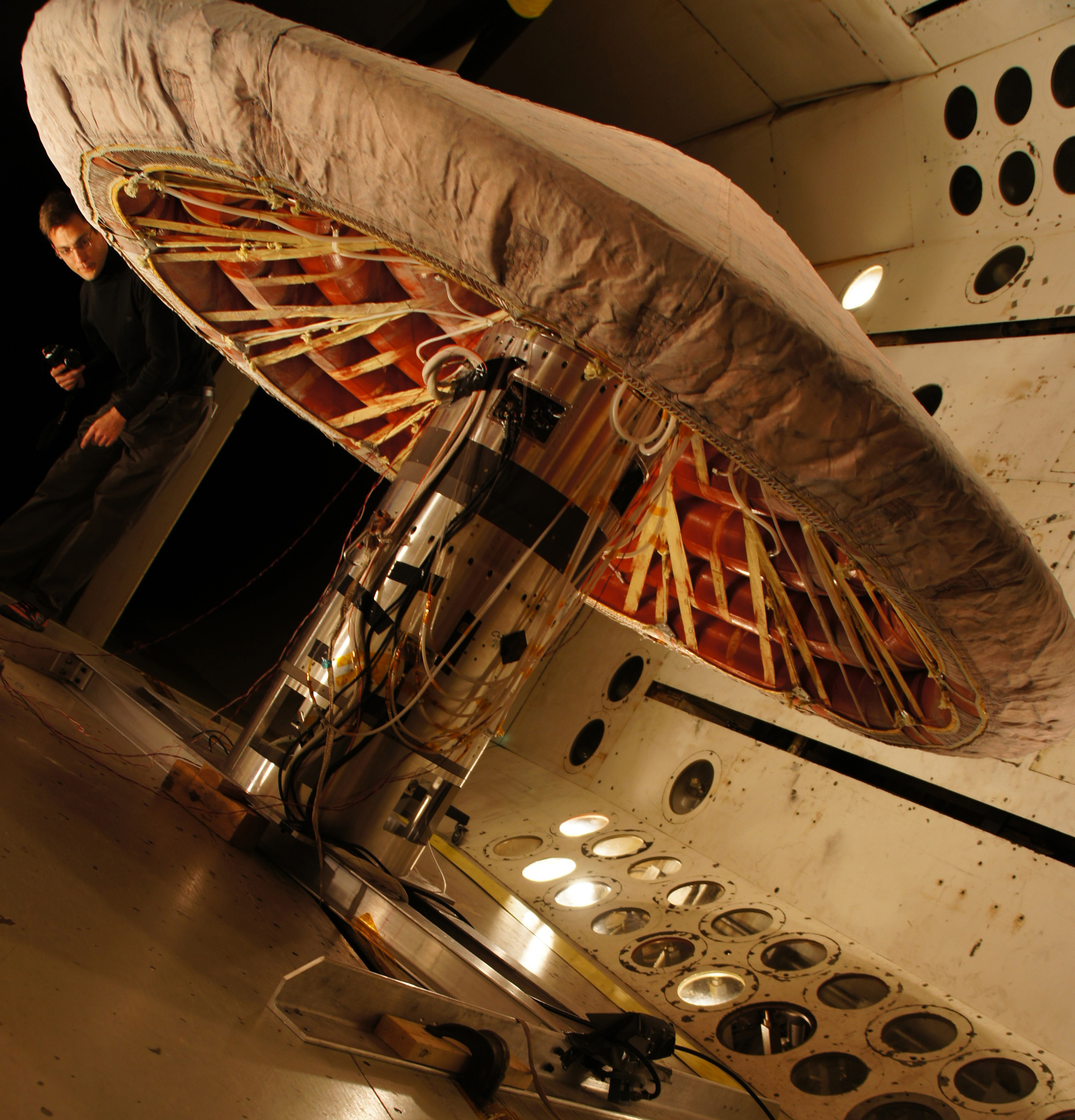

The 680-pound (308-kilogram) IRVE-3 heat shield consists of a cone made up of inflatable rings that are each wrapped in layers of thermal blankets. For the test flight, the prototype was packed inside a nose cone that measures 22 inches wide (56 centimeters). During the flight, the heat shield inflated with nitrogen gas, expanding to measure 10 feet (3 meters) across.

The IRVE-3 experiment launched atop a Black Brant 4 suborbital rocket from the Wallops Flight Facility. The entire test flight lasted approximately 20 minutes, NASA officials said.

As the heat shield re-entered Earth's atmosphere, it was exposed to 20 Gs of force (20 times the force of gravity) and temperatures of up to 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (537 degrees Celsius), as it traveled at blistering speeds of up to Mach 10, or 10 times the speed of sound.

The roughly $17 million test flight was part of NASA's Space Technology Program, which aims to foster the design and development of innovative technological solutions to the challenges of future space exploration.

"Without these technologies, we will not be able to perform the next generation of NASA missions that will go beyond low-Earth orbit with humans, and enable much greater, more ambitious science missions to the planets, and to explore the solar system and the universe," said James Reuther, deputy director of NASA's Space Technology Program.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.