Why Giant Alien Planets Like Some Orbits More than Others

Some zones encircling baby stars are far more popular than others, drawing crowds of giant planets while the other potential paths for orbits remain empty.Now computer simulations may reveal why, scientists say.

When astronomers began discovering giant alien planets similar to Jupiter and Saturn outside our solar system, they noticed that the orbits of these giants weren't spread out in regular intervals from baby stars. Instead, certain orbital distances seemed strangely attractive to these giants.

Researchers say they have apparently discovered the secret behind this mysterious clumping: high-energy radiation from these stars.

"Our models offer a plausible explanation for the pileups of giant planets observed recently detected in exoplanet surveys," said study lead author Richard Alexander, an astrophysicist at the University of Leicester in England.

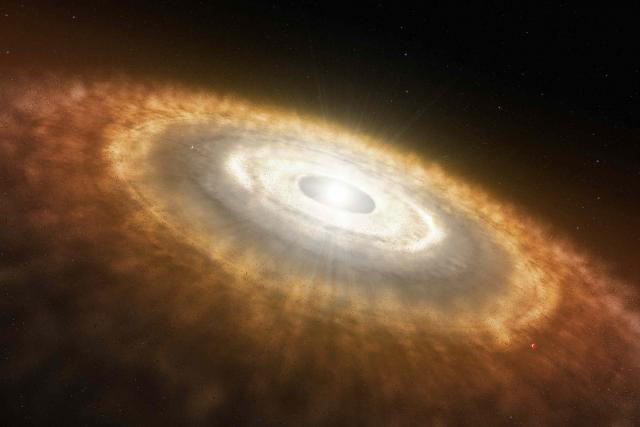

The radiation in question carves gaps in the protoplanetary disks of gas and dust that swirl around young stars and provide the raw materials for worlds. This process, called photo-evaporation, is the result of ultraviolet light and other high-energy photons from the star heating the disk material.

The disk material closest to the star gets very hot but is held in place by the strong gravity of the star. As such, any giant planets that migrate there from outer portions of the disk — often called 'hot Jupiters'— will stay, perhaps eventually getting all their gas stripped off.

Farther out, where the star's gravity is much weaker, the heated disk matter evaporates into space, forming the gaps. These gaps then essentially act as barricades that keep any more planets from spiraling inward.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The precise locations of those gaps depend on the mass of the planets, but they generally pop up in a zone between 1 and 2 astronomical units from a star like the sun. (One astronomical unit, or AU, is the average distance from Earth to the sun, about 93 million miles or 150 million kilometers.) [Gallery: The Smallest Alien Planets]

Supercomputer models of the effects of photo-evaporation on protoplanetary disks around young stars revealed "that the final distribution of planets does not vary smoothly with distance from the star, but instead has clear 'deserts' — deficits of planets — and 'pileups' of planets at particular locations," said study co-author Ilaria Pascucci at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

The experiments considered young solar systems with various combinations of giant planets at different locations and different stages in time, since researchers do not yet know exactly where and when planets form around baby stars. They found, just as observations of real alien stellar systems have shown, that giant planets migrate inward, dragged by protoplanetary material falling toward the star. However, once a giant planet encounters a gap cleared by photo-evaporation, it stays put, settling into a stable orbit around its star.

"The planets either stop right before or behind the gap, creating a pileup," Pascucci said. "The local concentration of planets leaves behind regions elsewhere in the disk that are devoid of any planets. This uneven distribution is exactly what we see in many newly discovered solar systems."

The fact that our solar system does not have giant planets piled up at 1 to 2 AU "suggests that our solar system may be rather unusual, but we can't yet tell how unusual," Alexander told SPACE.com. "Our models do predict some 'solar-system-like' systems — that is, with a Jupiter-mass planet at around 5 AU — but they're not the most likely outcome. Hopefully, within the next few years, observations of exoplanets will be able to tell us exactly how unusual the solar system is."

When astronomical surveys aimed at discovering extrasolar planet systems, such as the Kepler Space Telescope project, get better at spotting outer giant planets, Alexander and Pascucci expect to find more evidence for a pileup of giant planets around 1 AU.

"As our census of exoplanets grows in the coming years, it should provide us with an interesting way to test our understanding of planet-forming disks," Alexander said.

Future research also could model the effects of photo-evaporation on lower-mass planets and multiple-planet systems.

"Low-mass, terrestrial planets migrate differently than giant planets, and so far we've only looked at the giant planets," Alexander said. "However, in the coming months and years we're going to learn an awful lot about terrestrial planets, particularly through the results from the Kepler mission, so I'm keen to see if we can extend this study to look at lower-mass planets, too.

"Similarly, for now we only considered single-planet systems, but observations are finding more and more multi-planet systems, so I'm very interested in looking at how these results may change when more than one planet is present."

Alexander and Pascucci will detail their findings in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Pascucci will present the findings today (March 19) at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Woodlands, Texas.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us