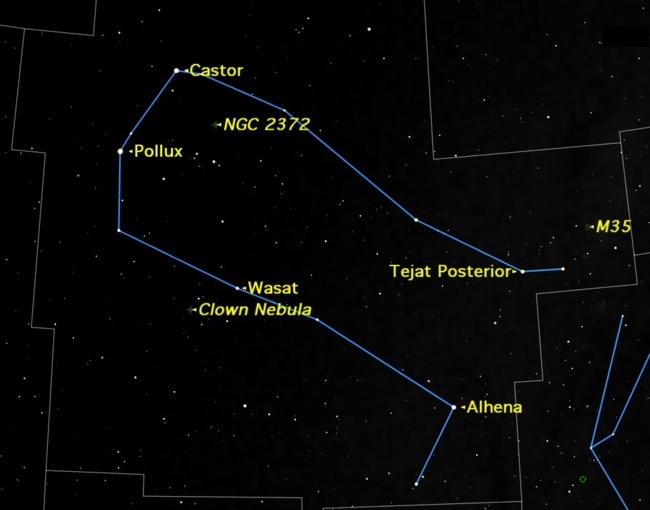

If you head outside around 10:30 p.m. local time this week and look straight up, you'll be looking directly at Gemini, the Twin Brothers.

The heads of the Gemini twins are the bright stars Pollux (yellowish) and Castor (white; a bit dimmer than Pollux). According to Greek mythology, the twins were the sons of Zeus and Leda and brothers of Helen of Troy.

Ancient mariners regarded Pollux and Castor as the patrons of seafarers, and in Elizabethan times they were also considered the protectors of all at sea. The expression "by Jiminy!" — an exclamation of surprise or awe —has been said to be a popular corruption of ancient swears by these patrons ("by Gemini!"). In addition, the twins were often billed as adventurers, warriors and famous navigators.

Most of the other stars that compose the constellation figures' arms and bodies are noticeably fainter than those in their heads and feet. A second-magnitude star known as Alhena marks one of Pollux's feet (on the astronomers' brightness scale of magnitudes, the lower the number, the brighter the star).

In places where light pollution hides many of the fainter stars, only Pollux, Castor and Alhena may be visible, forming a long wedge with its point aimed straight at Orion, the Mighty Hunter. [12 Must-See Skywatching Events in 2012]

Multi-star systems

Castor is actually a system of six stars, forming one of the most remarkable examples of a multiple star in the heavens. Pollux, too, may have faint companions, though we now know that none of them are physically related to this bright star.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Zeta Geminorum is a pulsating Cepheid star, its brightness changing nearly a full magnitude down from 4.4 and back in about 10 days. Propus is a complex system, a visual binary of magnitudes 3.3 and 6.5, with a period of about 500 years; the brighter member is a semi-regular variable, with an average period of 233 days. Additionally, an unseen companion star also periodically eclipses this star at intervals of 2,983 days.

Just above and to the right of Propus lies No. 35 in Charles Messier's catalog of bright objects in the heavens.

Located just off the trailing foot of Castor, Messier 35 can just be seen with the unaided eye on dark transparent nights. In low-power binoculars it may look like a dim, fairly large unresolved interstellar cloud, but look again. Even through light-polluted suburban skies, 7-power binoculars reveal at least a half dozen of the cluster's brightest stars against the whitish glow of about 200 fainter ones. M35 has been described as a "splendid specimen" whose stars appear in curving rows, reminding one of the bursting of a skyrocket.

Walter Scott Houston (1912-1993) wrote the Deep-Sky Wonders column in Sky & Telescope magazine for nearly half a century. He called M35 "one of the greatest objects in the heavens; a superb object that appears as big as the Moon and fills the eyepiece with a glitter of bright stars from center to edge."

Newfound comet?

Also located less than half a degree southwest from M35 is an unusual object that has brought a brief surge of excitement to countless numbers of amateurs over the years.

In a 6-inch telescope, it's a faint, circular cloud of light, which initially appears to the uninitiated as a possible new comet. The object, in fact, is the faint open star cluster NGC 2158. The compilers of many of the more popular star atlases had to draw a cutoff line as to what deep-sky objects to include, and not to include. Unfortunately, NGC 2158 fell just below the cutoff in most cases, which is why it is usually not mentioned and why many amateur astronomers have grown up knowing nothing of it.

But if you get a chance to train a telescope on M35 and come across this small, faint patch of nebulosity a short distance away, at least now you won't be making the "comet mistake" that so many others have made. Houston himself fell into this trap, later calling NGC 2158 his "lasting monument to my early, somewhat careless, years of observing."

I myself am not embarrassed to relate this personal episode: In September 1985, while camping in the Adirondacks of northern New York, I was scanning the Orion-Gemini region with my 10-inch Dobsonian telescope looking for Halley's Comet, which was then approaching the sun and the Earth. It was then that I, too, stumbled across NGC 2158. For several minutes I thought I was looking at "Comet Rao," but after composing myself and checking Volume Two of Burnham's Celestial Handbook, I came back down to Earth.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.