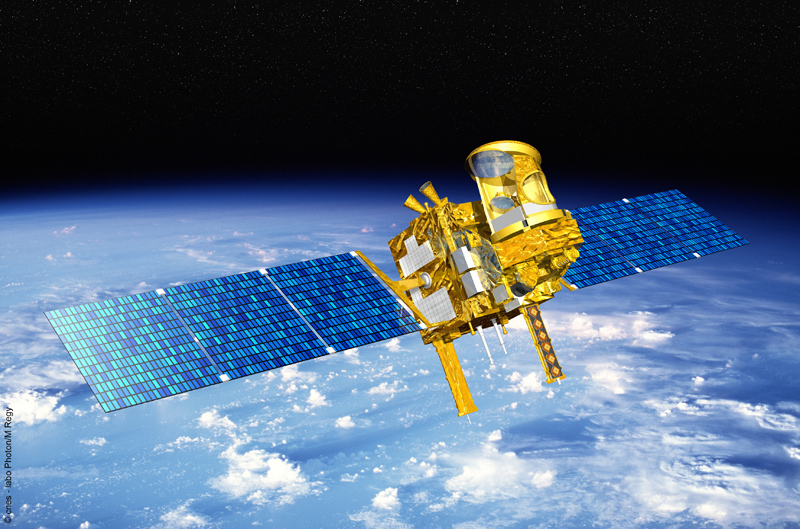

Tropical Climate Satellite Soars for India, France

An Indo-French satellite launched on an international climate research mission last week, ascending into space to track tropical cyclones, monsoons and storm systems for at least three years.

The 2,204-pound Megha-Tropiques satellite lifted off at 0530 GMT (1:30 a.m. EDT) on Oct. 12 from the Satish Dhawan Space Center on Sriharikota Island. It was 11 a.m. local time at the launch site, which is located on India's east coast about 50 miles north of Chennai.

The four-stage Polar Satellite Launch Vehiclereached orbit and deployed Megha-Tropiques about 22 minutes later, then three more secondary payloads separated to begin their missions.

"The PSLV C-18 flight has been a grand success," said K. Radhakrishnan, chairman of the Indian Space Research Organization. "Very precisely, four satellites were injected into a circular orbit and the difference in what we planned and what we achieved is just two kilometers."

It was the 20th flight of the PSLV, which entered service in 1993 and has flawlessly delivered remote sensing, communications and scientific satellitesto space at a 90 percent success rate. Wednesday's launch used the "core-alone" configuration of the PSLV with no strap-on solid rocket boosters.

Embarking on an international research mission, Megha-Tropiques has four instruments designed to probe the structure of the atmosphere, measure temperature and water vapor, and study the Earth's radiation budget. [Earth Checkup: 10 Health Status Signs]

Megha means "cloud" in Sanskrit, the ancient language of India.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This is only the second satellite whose focus is on weather in the tropics, whether it's the monsoons, or whether it's climate change or convective systems," said R. Narasimha, the chief scientist for India's contribution to the Megha-Tropiques mission. "This satellite is going to give us exciting science, but it's also something which will be very useful to society, our nation and the world."

India built the spacecraft, provided the launch and contributed to two instruments. France supplied the satellite's water vapor profiling sensor and the radiation detector.

France's investment in the mission totaled 40 million euros, or about $55 million, not including labor costs, according to Didier Renaut, director of meteorology and climate programs at CNES, the French space agency.

In an interview Wednesday, Renaut said India had about a 60 percent share in Megha-Tropiques, with France adding the remaining 40 percent.

Renaut said Megha-Tropiques has two main goals.

"The first objective is general scientific research into the tropical climate, convective systems in the tropics, contributions to the rain budget in the tropics, and things like that," Renaut said. "The second one is a more operational goal, to use more real-time Megha-Tropiques data to watch over the meteorological phenomena in the tropics, such as convective systems, monsoon rain systems and tropical cyclones."

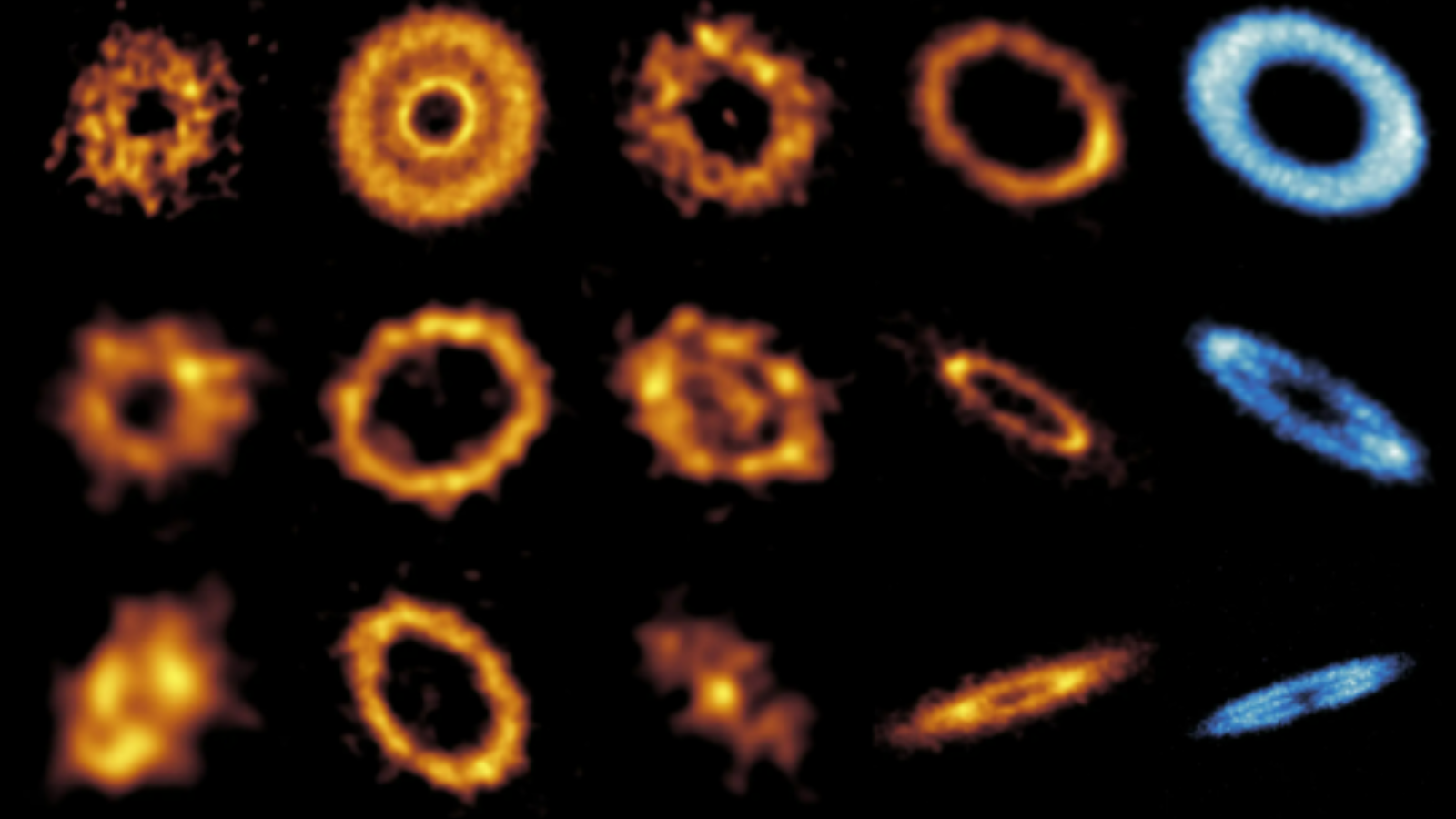

Long-term research will benefit from Megha-Tropiques by improvements in climate computer models. Megha-Tropiques could help scientists better understand how water and energy come together in the tropics to form clouds and storms.

Real-time forecasters will have daily access to Megha-Tropiques data to help with hurricane and storm outlooks.

Megha-Tropiques is one of the first spacecraft to launch for the Global Precipitation Measurement program, an international network of satellites led by NASA and Japan to track worldwide weather.

"We need to measure all around the world and with repeated measurements, so we need several satellites," said Yannick d'Escatha, president of CNES.

The satellite orbits about 538 miles above Earth, crisscrossing the equator to cover an area stretching between 20 degrees north and south latitude. Most tropical cyclones develop in this band, which also includes the perpetually stormy intertropical convergence zone, where tradewinds from the northern and southern hemispheres collide and generate rain showers. [The World's Weirdest Weather]

"That (orbit) allows a very frequent revisit over the tropics, up to six passes a day for certain parts of the tropics," Renaut said.

Officials selected the orbit to allow regular observations of fast-developing clouds and storms.

"Improving the understanding of climate and weather systemsis of paramount significance for a monsoon-dependent agragrian economy like India that also goes through the vagaries of cyclones and drought frequently," Radhakrishnan said.

After its genesis among French scientists in 1993, the Megha-Tropiques project was threatened by French budget trouble in 2002, but India agreed to take charge of the satellite construction, leading to a formal agreement for the mission in 2004.

"The teams at CNES and ISRO have worked together on these instruments despite being thousands of kilometers apart, using very different methods," said Nadia Karouche, the Megha-Tropiques project manager at CNES. "Although we have communicated constantly, we were afraid that misunderstandings might lead to some nasty surprises when we moved to the assembly phase. But everything worked out fine."

According to Renaut, engineers will finish in-orbit testing of the spacecraft in two or three months, then it will take about six months to calibrate the scientific instruments and validate their results.

"What is planned is that after about nine months after the launch, there will be the beginning of the operational phase with the opening of the data to every scientific user in the world," Renaut said.

Copyright 2011 SpaceflightNow.com, all rights reserved.

Stephen Clark is the Editor of Spaceflight Now, a web-based publication dedicated to covering rocket launches, human spaceflight and exploration. He joined the Spaceflight Now team in 2009 and previously wrote as a senior reporter with the Daily Texan. You can follow Stephen's latest project at SpaceflightNow.com and on Twitter.