Missing Supernova Dust Mystery Solved

The violent death of stars has long been thought to disperse heavy elements into the surrounding hydrogen-dominated universe. But observations of the remnants of these stellar deaths, called supernovas, have not revealed the large quantities of dust needed to support this theory — until now.

Using the European Space Agency's Herschel Space Observatory, scientists detected enough cold dust to make up about half of the sun — more than a hundred thousand times the amounts previously seen.

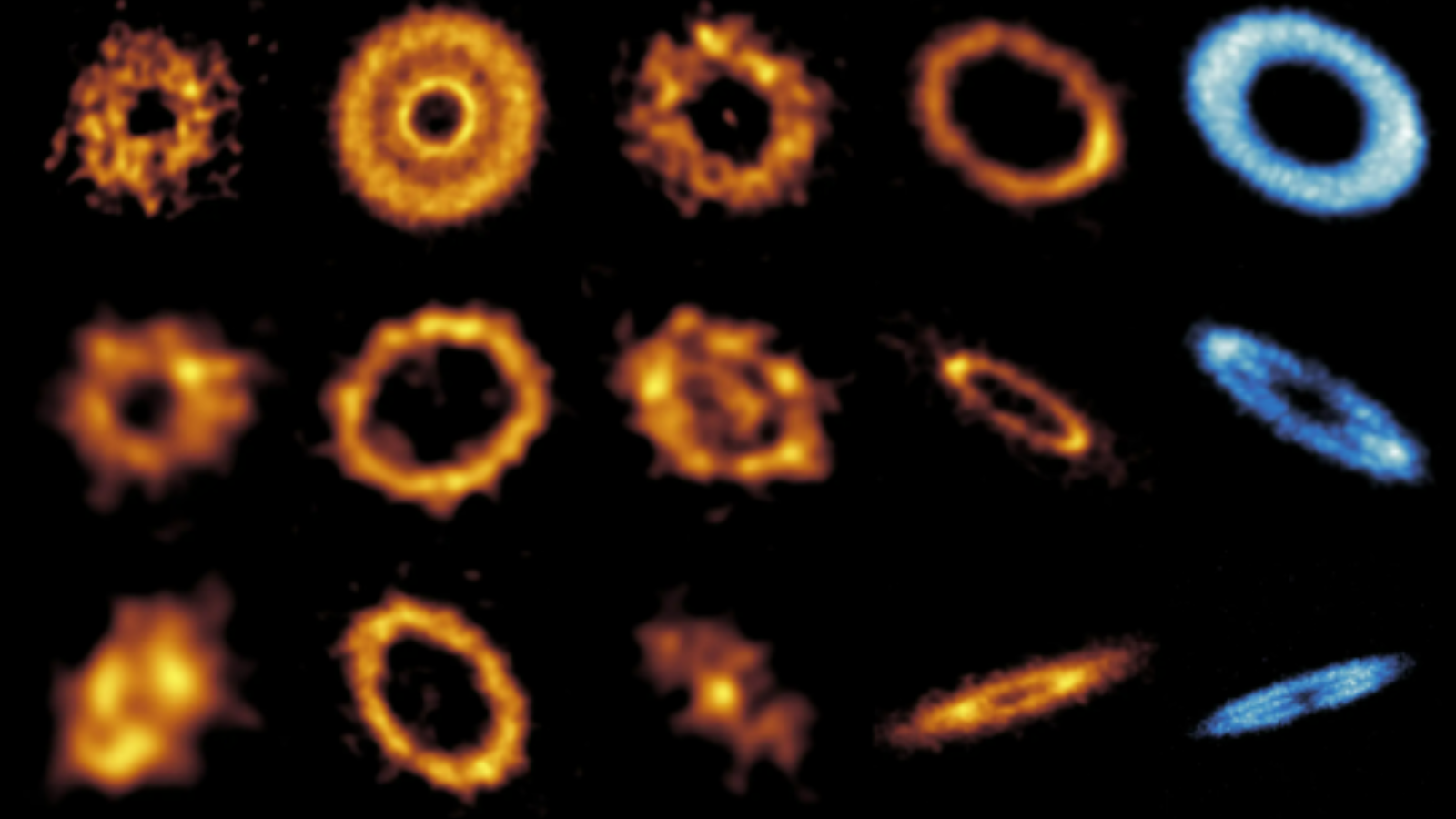

Supernovas are dust factories, converting the hydrogen and helium that make up stars into heavier elements that can be fused only under the extreme energies created by a dying star's explosion.

Yet when astronomers have pointed instruments at these stellar corpses, the dust they found was only a few millionths of what's present in the sun. Such a limited output failed to explain the significant quantities of dust found in galaxies born less than a billion years after the Big Bang, where other possible methods of creating the dust were just too slow. [Supernova Photos of Star Explosions]

Missing Dust

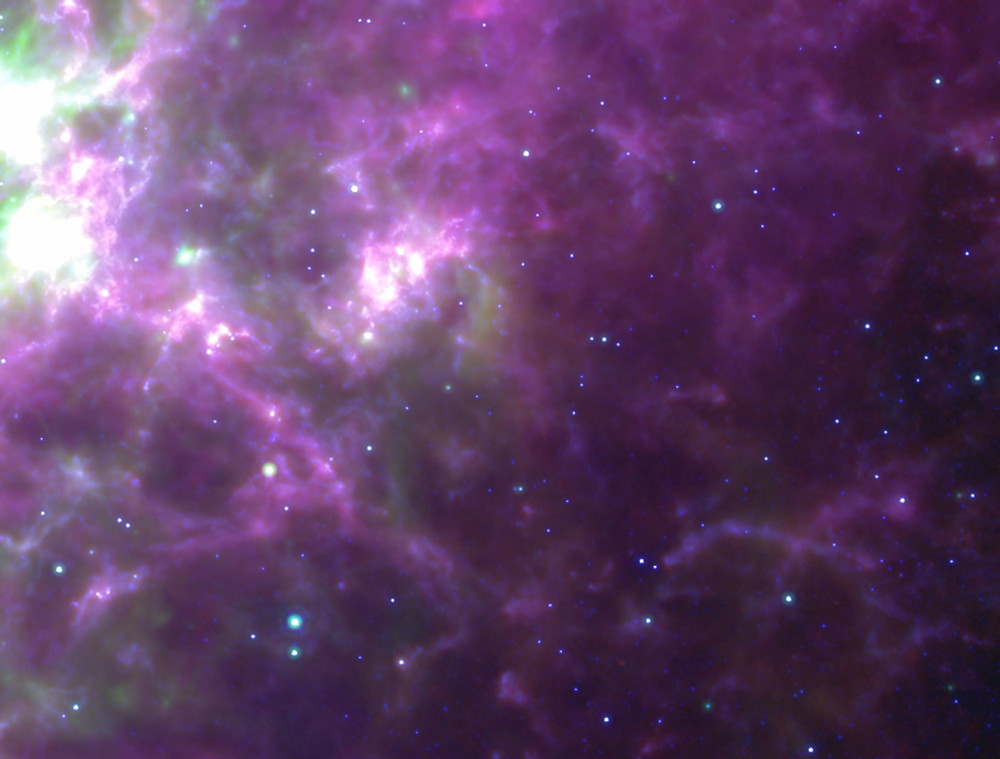

While using Herschel to survey the nearby galaxy known as the Large Magellanic Cloud, the team saw a bright glow around a young supernova called SN1987A. They quickly realized that the emission came from dust almost 300 degrees Fahrenheit (160 K) cooler than previous instruments had registered.

"This discovery was actually surprising," primary author Mikako Matsuura, of University College London, told SPACE.com. "We did not intend to observe this particular object."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Launched in 2009, Herschel studies objects in the far infrared and submillimeter wavelengths, an area that previous telescopes could not venture into with such detail. Orbiting the Earth, it avoids the atmosphere that quickly absorbs the hard-to-read radio waves, allowing it to see cold dust invisible to other wavelengths.

And dust it saw. The amount of cooler dust around the supernova remnant was approximately half the mass of the sun, significantly larger than previous studies had recorded.

According to theory, in order to account for the amount of the dust within galaxies, supernovas need to distribute somewhere between a tenth to a whole solar mass of dust.

"This is the first time anything approaching that amount has been found in a supernova," Mike Barlow, also of Open University, told SPACE.com. Barlow contributed to the results, reported online in today's (July 7) issue of the journal Science.

A New Supernova

When SN1987A burst into view on Feb. 23, 1987, it provided modern astronomers with the first detailed glimpse into the death of a star. Over the past two decades, it has become one of the most-studied objects in the sky.

"Ever since this supernova exploded, it has been a template," Barlow said.

Astronomers have been able to monitor the gas released in the explosion as it moves through space.

"It's astrophysics in real time," Barlow said.

Even without the detailed exploration Herschel provided, studying older supernovas can be difficult. Astronomers must try to ascertain how much of the dust comes from the supernova itself, and how much already existed in the background.

The dust from young supernovas like SN1987A hasn't had time to diffuse, which is one reason it is such a find.

"The detection by Herschel of a half a solar mass of dust in the ejecta of SN 1987A provides the first reliable evidence that supernovae from high mass stars can account for the amounts of dust seen in these [early] galaxies, and that they probably still make an important contribution," Barlow said in an email.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky