Life's Building Blocks May Have Been Found on Mars, Research Finds

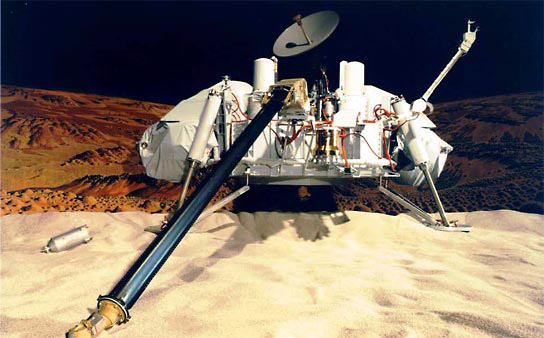

NASA's Viking landers may have detected the ingredients for life on Mars after all, according to a new study.

Back in the 1970s, the two Viking probes scooped up and heated Martian dirt, then looked for organic molecules — the carbon-based building blocks of life as we know it — in the samples. The landers found little, aside from two strange chlorine compounds that researchers at the time attributed to contamination from cleaning fluids.

But the new study suggests that the soil did indeed contain organics, which can have biological or nonbiological origins. They were just destroyed before Viking could detect them.

"This result is saying that there are organic molecules on Mars," study co-author Chris McKay, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., told SPACE.com. "It doesn't say anything about life now, or life in the past. But it does open up the possibility of searching for organic molecules produced by life, and that's very exciting."

Accounting for perchlorate

A 2008 find by NASA's Phoenix Mars lander helped motivate McKay and his colleagues, led by Rafael Navarro-Gonzalez of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, to take another look at the Viking results.

Phoenix detected a chlorine-containing chemical called perchlorate at its landing site, near the Martian north pole. The researchers suspected that perchlorate may have produced what Viking found, destroying original soil organics and leaving behind the two chlorinated compounds, chloromethane and dichloromethane.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So the scientists performed a lab experiment. They grabbed some dirt from Chile's Atacama Desert — widely considered to be a Martian analog environment — and spiked it with perchlorate. Then they heated the mixture up in the lab, just as the Viking landers did on Mars.

Just as with Viking, the researchers found chloromethane and dichloromethane.

"The simplest, most reasonable explanation of the Viking results is that there were organics in the soil, and they were consumed by the perchlorate," McKay said. "I think it's pretty convincing."

Navarro-Gonzalez, McKay and their colleagues reported their findings last month in the Journal of Geophysical Research - Planets, though the results were first announced last September.

Not proof of life

The results don't prove that life exists — or ever existed — on Mars. While organics are associated with life here on Earth, that's not necessarily the case elsewhere in the solar system, McKay said.

Organic compounds seem to be common, for example, on asteroids, comets and the icy bodies orbiting the sun in the Kuiper Belt, beyond Neptune.

But the prospect of Martian life may be a bit more likely now, since Viking seemingly found life's building blocks in the planet's red dirt more than three decades ago.

"There's a possibility that some of those organic molecules are in fact biomarkers," or indications of the presence of life, McKay said. "That's exciting."

Following up with the next Mars rover

Scientists should soon get a chance to confirm the presence of organics in Mars' soil. NASA's Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover, also known as Curiosity, is slated to land on the Red Planet in August 2012. As part of its mission to determine Mars' potential to host life — either today or in the past — the car-size rover will search for organic molecules.

MSL's instruments will attempt to extract organics using heat, like Viking did. But the new rover will also use a liquid method, which should clear things up; perchlorate doesn't destroy organic molecules if it's not heated to high temperatures.

"My prediction is that MSL, when it does the heat mode, will see nothing," McKay said. "But when it does the liquid extraction mode, it will see the organics."

Should MSL indeed confirm organics on Mars, the next step would likely be to figure out if they have a biological or nonbiological origin. That may require another mission, according to McKay.

"If MSL finds an interesting diversity and complexity of organics, then we could do a follow-up mission that's targeted to look for biologically formed organic molecules," McKay said. "That would be very interesting."

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.