Cold War-Era Satellites Spy on Himalayan Glaciers

SAN FRANCISCO — The Cold War may have ended decades ago, but spy satellites' data from that era are now being used for a new mission: tracking environmental change in the Himalayas.

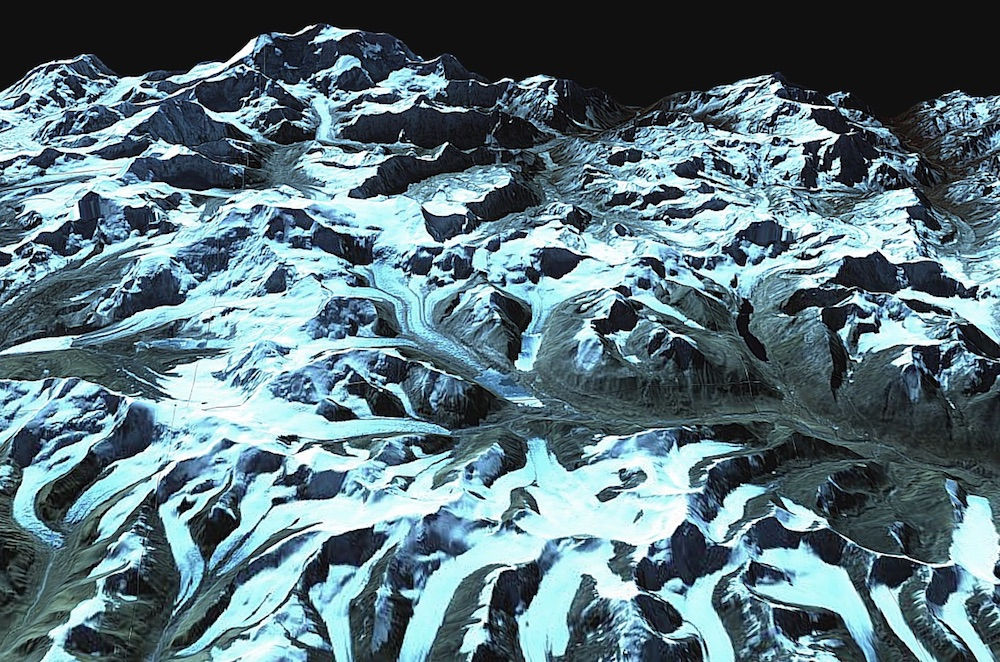

Using declassified spy satellite data, researchers have created 3D images of glaciers across the Himalayas, scientists said. These maps provide the first consistent look at 40 years of glacier change across Asia's high-mountain region. Early results from these models were presented here Monday (Dec. 12) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

The new 3D maps revealed how the Himalayas' glaciers have behaved in a changing climate. For instance, the first results covering 21 glaciers in just the Bhutan region showed that the glaciers have been losing more ice than they have been gaining, the researchers said. [Photos of Melt: Glaciers Before and After]

By comparing the spy satellite images from 1974 with images taken in 2006 using the ASTER imaging instrument aboard NASA's Terra satellite, the scientists estimated annual average mass loss (if melted to water) to be at least 7 inches (0.18 meters) lost over the entire surface of each glacier.

"Life depends on water, so changing the amount or timing of how that water reaches a community or an ecosystem is going to have an impact," said lead researcher Josh Maurer, a graduate student at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York City.

The researchers said that about 20 percent of the world's population relies on the Himalayan glaciers' seasonal meltwater. Along with monsoon rain and snowfall, the glacial water sources are a source of drinking water, agriculture and hydropower energy.

The new 3D-mapping tool is helping scientists more consistently quantify glacier change, said co-author Summer Rupper, a scientist at the University of Utah who has conducted many expeditions to measure changing glacier mass.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"A glacier may be losing mass for two reasons — it may be from melt or it may be getting less snow," Rupper said. "Remote sensing can give you the net change but not the cause. The power is when you can couple that with on-the-ground information to put that [net change] into perspective."

Satellites, including the Earth-monitoring Landsat 8 satellite, can provide scientists with detailed views of glacier change from orbit. However, knowledge of historical change — particularly in the Himalayan region — has been limited, the researchers said.

Scientists gathered the images used to create the new 3D historical maps of Himalayan glaciers from a U.S. spy-satellite program code-named Hexagon, which operated from 1971 to 1986. During the Cold War, Hexagon's 20 satellites orbited Earth, capturing overlapping images. Those pictures allowed researchers in the new study to construct 3D views.

However, when the U.S. government first declassified the spy satellite data in 2011, scientists manually built 3D elevation models by matching landmarks between images and calculating the satellite angle — a time-consuming process with inconsistent results.

Maurer and his colleagues developed an automated process that creates consistent 3D models of glaciers as they appeared over time.

"It can take years for a glacier to fully respond to a change in climate, so looking back several decades gives us a better signal," Maurer said in a statement. "While we have volume changes over the last decade or so from more modern remote-sensing platforms, glacier response times can be longer than that. The declassified spy-satellite data allows for [finding] actual ice-volume changes over those longer time scales."

Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Kacey Deamer is a journalist for Live Science, covering planet earth and innovation. She has previously reported for Mother Jones, the Reporter's Committee for Freedom of the Press, Neon Tommy and more. After completing her undergraduate degree in journalism and environmental studies at Ithaca College, Kacey pursued her master's in Specialized Journalism: Climate Change at USC Annenberg. Follow Kacey on Twitter.