This Deepest View Ever of the Orion Nebula Reveals Hidden Objects

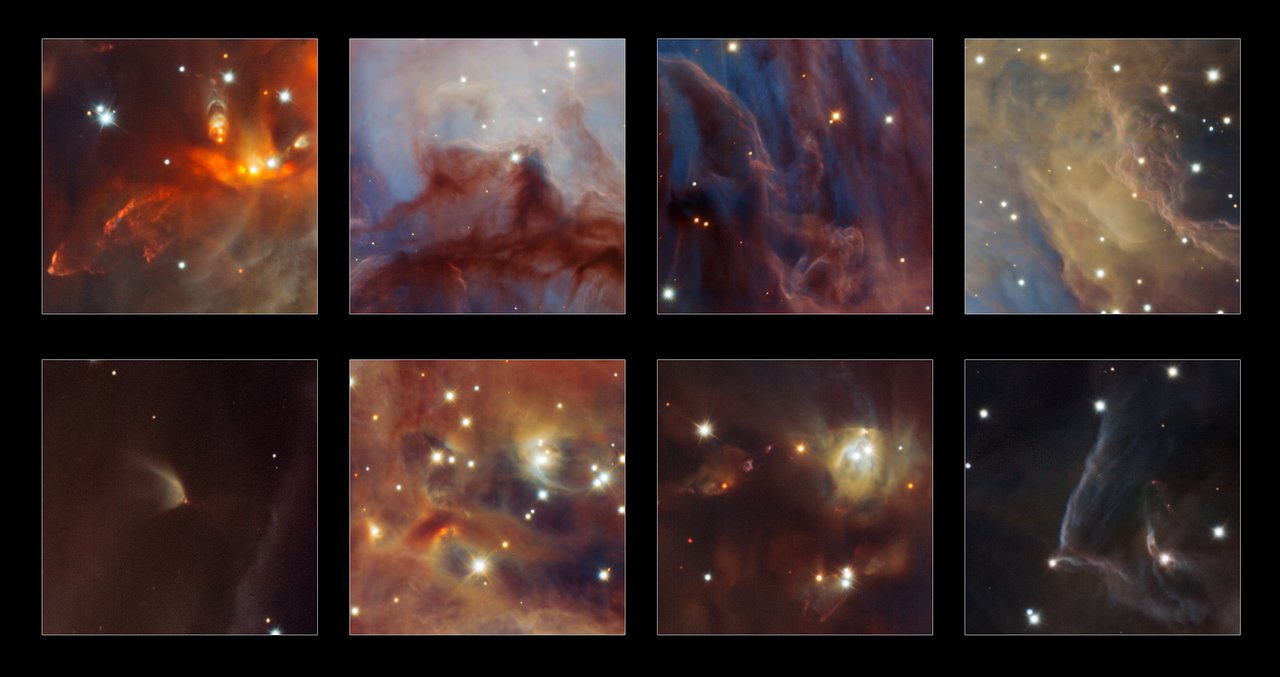

A new view of the Orion Nebula, the "deepest and most comprehensive view ever," reveals a preponderance of low-mass, planet-size objects in the famous star-forming region.

The new images, which you can tour in this awesome new video, use infrared data from European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Very Large Telescope to document the nebula's thick, glowing cloud of gas. With the hawk-like gaze of the telescope's HAWK-1 camera, researchers found 10 times more planet-mass objects and nearly planet-mass failed stars called brown dwarfs than ever seen before.

"Understanding how many low-mass objects are found in the Orion nebula is very important to constrain current theories of star formation," Amelia Bayo, co-author on the new paper, said in a statement. "We now realize that the way these very low-mass objects form depends on their environment." Bayo is an astronomer at University of Valparaíso in Chile and the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany. [The Splendor of the Orion Nebula (Photos)]

The Orion Nebula, which forms the middle "star" on the sword of the Orion constellation, is an enormous star-forming region located about 1,350 light-years from Earth. As its clouds of gas collapse inward to form stars, the new stars' ultraviolet radiation ionizes the gas around them and causes the nebula to glow. (It's visible from Earth with the naked eye, and spectacular in a telescope.)

The unexpectedly high proportion of very-low-mass objects raises questions about the star formation process and scientists' understanding of the "stellar initial mass function." This is a description of the ratio of differently sized stars that form as gas collapses together in a star-forming region. Previously, researchers observed the most common size as about one-fourth the mass of the sun, but in the Orion nebula, there seems to be another peak of much lower mass.

If active regions of interstellar space, like the Orion Nebula, form lots of small objects as well as massive stars, it could mean there are many more planet-size objects in the universe than previously thought. The observatory's European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT), which is scheduled to begin operations in Chile in 2024, would be able to spot those far-distant objects further out in space, ESO officials said in the statement.

"Our result feels to me like a glimpse into a new era of planet- and star-formation science," Holger Drass, lead author on the work and astronomer at Ruhr-Universität Bochum in Germany and the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, said in the statement. "The huge number of free-floating planets at our current observational limit is giving me hope that we will discover a wealth of smaller, Earth-sized planets with the E-ELT."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new work was detailed today (July 12) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.