Wild Ride to Mars: Inside ExoMars' Schiaparelli Lander Prototype

The ExoMars mission launching Monday (March 14) will pack an orbiter as well as an ambitious Mars lander prototype that will make the challenging descent to a controlled landing on Mars.

The little lander, called Schiaparelli, will demonstrate the technology necessary to land a life-hunting rover on ExoMars' next mission. It's about 1,320 pounds (600 kilograms) packed into a 7.9-foot (2.4 meter) diameter package, counting the outstretched heat shield.

Schiaparelli and the orbiter will travel for seven months after the launch to get to Mars, but they'll part ways about three days before reaching the Martian atmosphere, on Oct. 16, European Space Agency researchers said in a statement. At that point, Schiaparelli will separate and then coast toward Mars, still in hibernation to conserve power. [How Europe's ExoMars Missions to Mars Work (Infographic)]

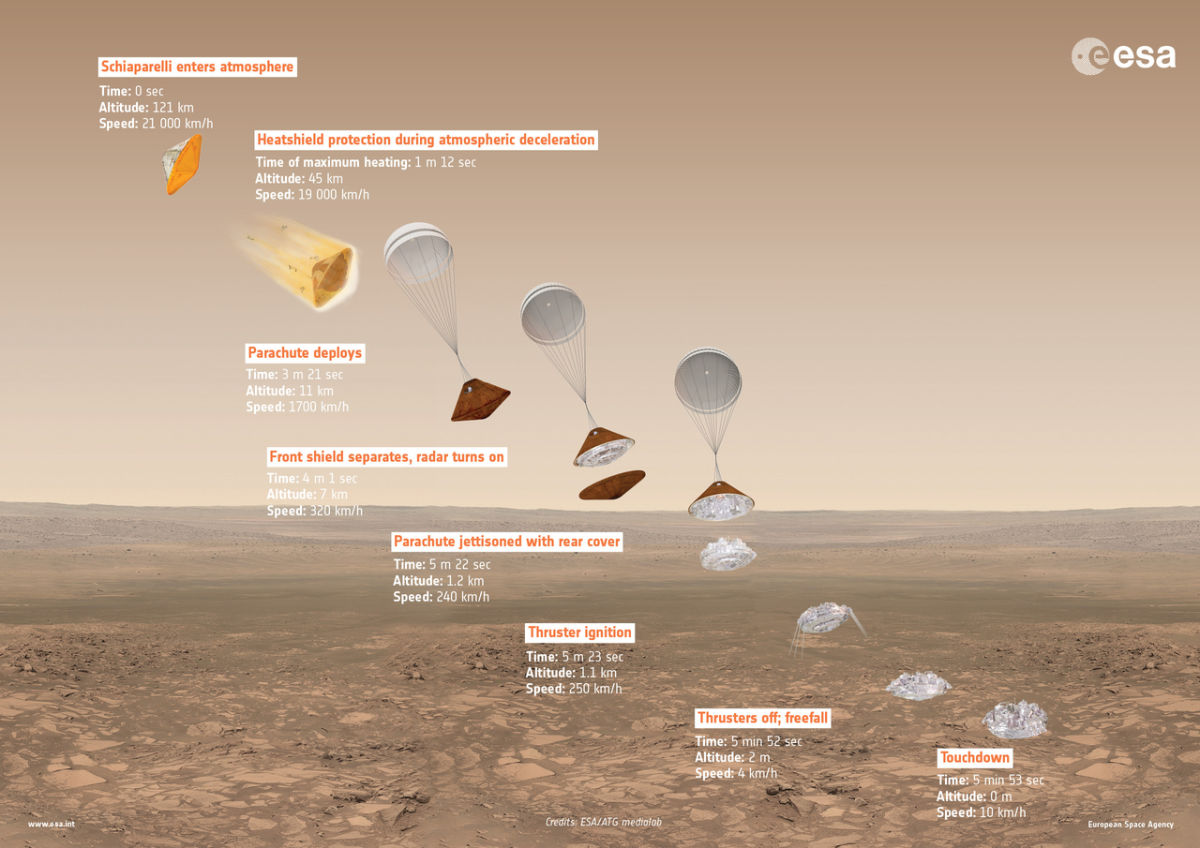

A few hours away from the Martian atmosphere, at an altitude of 76 miles (122.5 km), the module will come to life while traveling approximately 13,050 mph (21,000 kph). Its heat shields will slow it down as it enters the atmosphere, braking to about 1,025 mph (1,650 kph), and then it will deploy the 39-foot (12 m) parachute.

As it hurtles downward, Schiaparelli's heat shields will reach temperatures of about 2,732 degrees Fahrenheit (1,500 degrees Celsius).

After slowing even further, the experimental lander will release its front and back heat shields and switch on radar sensors to figure out how far it is from the Martian surface. The parachute will be left behind on the back heat shield, so to slow down even more, the lander will switch on its thrusters until it gets down to about 6.6 feet (2m) off the ground, slowed to just 4.3 mph (7 kph).

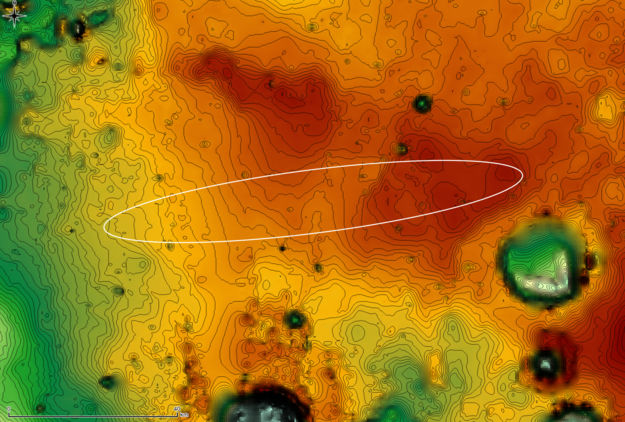

Then it'll switch off its thrusters and drop to the ground, and the bottom of the module, like the crumple zone on the front of a car, will break its fall as it plunks down on the surface of Mars' Meridiani Planum, possibly within view of NASA's Opportunity rover.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A lot for the lander to get through in just 6 minutes since entering the atmosphere.

For as long as its leftover battery life lasts — just a few days, likely — the lander will study Mars' wind speed and direction, humidity, pressure, air temperature, atmosphere transparency, electric fields and more, sending its measurements up to the orbiter through two antennas. (It will send measurements during the 6-minute landing process, too.)

Any science measurements the lander sends from the surface is a bonus: The lander's main purpose is to pave the way for the rover launching in 2018, officials said in the statement. Using knowledge gained from Schiaparelli, that future rover will be able to land safely and begin its hunt for signs of life.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.