Winter Solstice: The Sun Stands Still on Saturday

This coming Saturday (Dec. 21) marks one of the four major way stations on the Earth’s annual journey around the sun.

Because of the tilt in the Earth’s axis of rotation, the sun appears to rise and fall in our sky over the course of a year. It’s not the sun itself moving, but the Earth moving relative to the sun.

The Earth’s axis currently points in a northerly direction close to the second-magnitude star Polaris, also known as the Pole Star. Everything in the sky, including the sun, appears to revolve around this almost fixed point in the sky. [Season to Season: Earth's Equinoxes & Solstices (Infographic)]

Because the Earth’s axis points to Polaris no matter where Earth happens to be in its orbit, the sun appears to move over the year from 23.5 degrees north of the celestial equator on June 21 to 23.5 degrees south of the celestial equator on Dec. 21.

The sun crosses the equator travelling northward around March 21 and going southward on Sept. 21, in celestial events known as "equinoxes" (from the Latin for "equal night," as day and night are of roughly equivalent length on these dates.) The exact dates vary a little bit from year to year because of leap years.

On Dec. 21, the sun stops moving southward, pauses, and then starts moving northward. This pause is called the "solstice," from the Latin words "sol" for "sun" and "sisto" for "stop." Similarly, on June 21 the sun stops moving northward and starts moving southward.

These four dates have been extremely important to humanity since we first started to grow crops 10,000 years ago. Our ancestors have built amazing structures over the millennia to track these important landmarks. For example, Stonehenge in England was built as an astronomical observatory, its stones precisely oriented to detect the extremes of the sun’s movement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Our calendar is based on the dates of the equinoxes and solstices, though errors over the years have caused the calendar to shift by 10 days from the celestial dates. Many cultures in the world use the winter solstice to mark the beginning of the year. The other three dates neatly divide the year into quarters, or seasons.

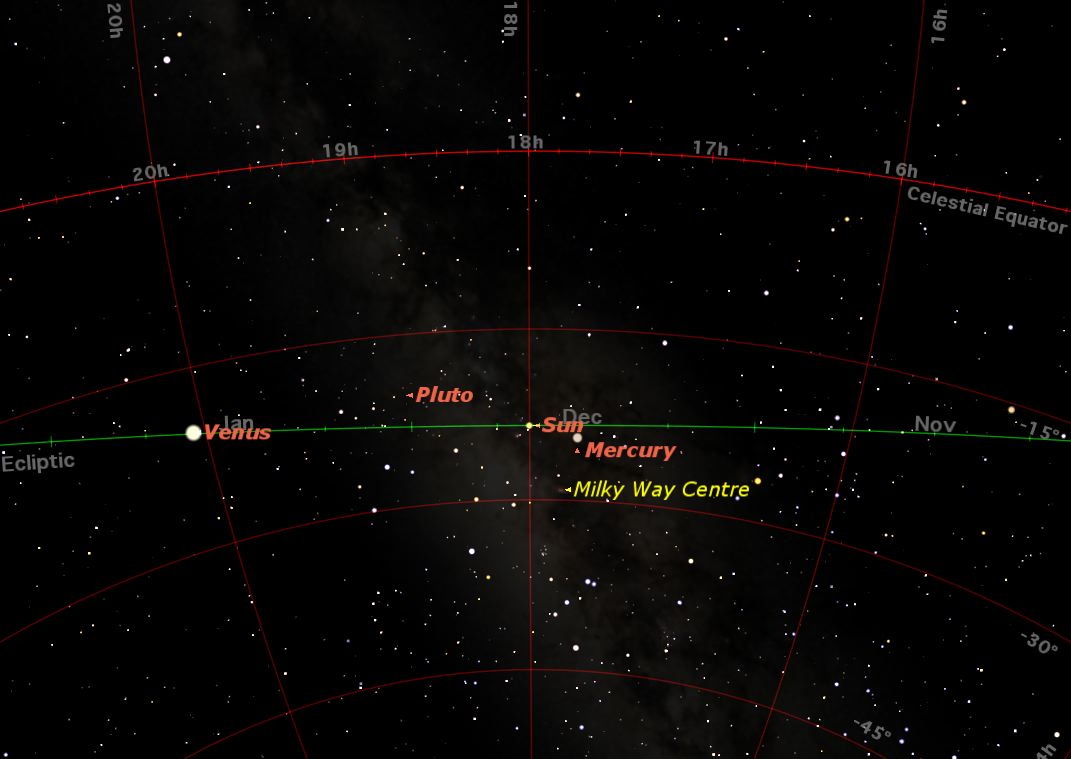

The accompanying chart shows what the sky would look like this coming Saturday at precisely 12:11 p.m. EST (1711 GMT), if somehow the sun’s light could be dimmed so that you could see the background stars. The sun is traveling from right to left along the green line, called the "ecliptic" because eclipses happen along it. The sun is as far south as it can get at that instant, and begins moving northward immediately.

The celestial equator is marked by the red line, far to the north of the sun's position. You can see the inner planets gathered around the sun. Venus, off to the left, is moving toward the right, and will pass between us and the sun on Jan. 11. Mercury, to the right, is moving to the left and will pass behind the sun on Dec. 29. Pluto is on the far side of the sun and will pass behind it on Jan. 1.

Notice the Milky Way crossing diagonally through the chart. That’s because our solar system is not oriented in any particular way relative to the plane of the Milky Way. The center of the Milky Way is almost directly below the sun’s position on Dec. 21, something that was made much of last year. As astronomers pointed out repeatedly then, the sun passes in front of the Milky Way’s center every year, not just in 2012. Because the Milky Way’s center is so far away, 27,000 light-years distant, it has no measurable effect on the Earth.

For some odd reason, the winter solstice has come to be known as "the first day of winter" while the summer solstice continues to be called correctly "midsummer’s day." Although Dec. 21 gets less sunshine than any other day in the year in the Northern Hemisphere, it is far from the coldest day of the year, because the weather always lags a month or two behind the exact calendar dates.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.