'Why Am I Taller?' explores what happens to the human body in space

Authors Elizabeth Howell and Dave Williams discuss their new book looking at how spaceflight affects the human body.

Spaceflight pushes the human body to new limits.

Aside from the stresses that riding aboard rockets traveling faster than the speed of sound can put on the body, spending extended periods of time off Earth can change the human body in surprising ways. Space-related health effects ranging from increased risks of radiation exposure and a wide range of genetic mutations in blood-forming stem cells to even changes in the shape of astronauts' eyes show that the human body truly did not evolve to thrive in microgravity and the radiation-filled environment of outer space.

Still, as access to space continues to expand, and as humanity plans to travel farther than ever to the moon and Mars, it's imperative that we better understand the effects of spaceflight on the human body and find ways to mitigate them. With that thought in mind, authors Elizabeth Howell, who's a staff writer at Space.com, and Dave Williams, a doctor and former Canadian Space Agency astronaut, wrote "Why Am I Taller?: What Happens to an Astronaut's Body in Space" (ECW Press, 2022), a book examining the clinical challenges of spaceflight and how they might aid medicine here on Earth.

Space.com spoke with Howell and Williams to discuss the book, what readers can take away from it, and how space medicine is about much more than keeping astronauts alive and healthy in orbit and beyond.

Related: Handheld laser device can quickly diagnose astronaut health in space

"Why Am I Taller?: What Happens to an Astronaut's Body in Space" just $17.95 on Amazon.

"Why Am I Taller?" examines what happens to an astronaut's body in space and how we can apply lessons learned in orbit here on Earth.

The following conversation has been edited for length.

Space.com: Dave, you got to fly two space shuttle missions and spend time on the International Space Station during your time as an astronaut. What's one of the big takeaways from your experiences?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Dave Williams: If something bad happens out there, you may have the rest of your life to solve the problem. So it's always this, this contrast between the beauty of space that's just absolutely incredible, with the risk of being in space.

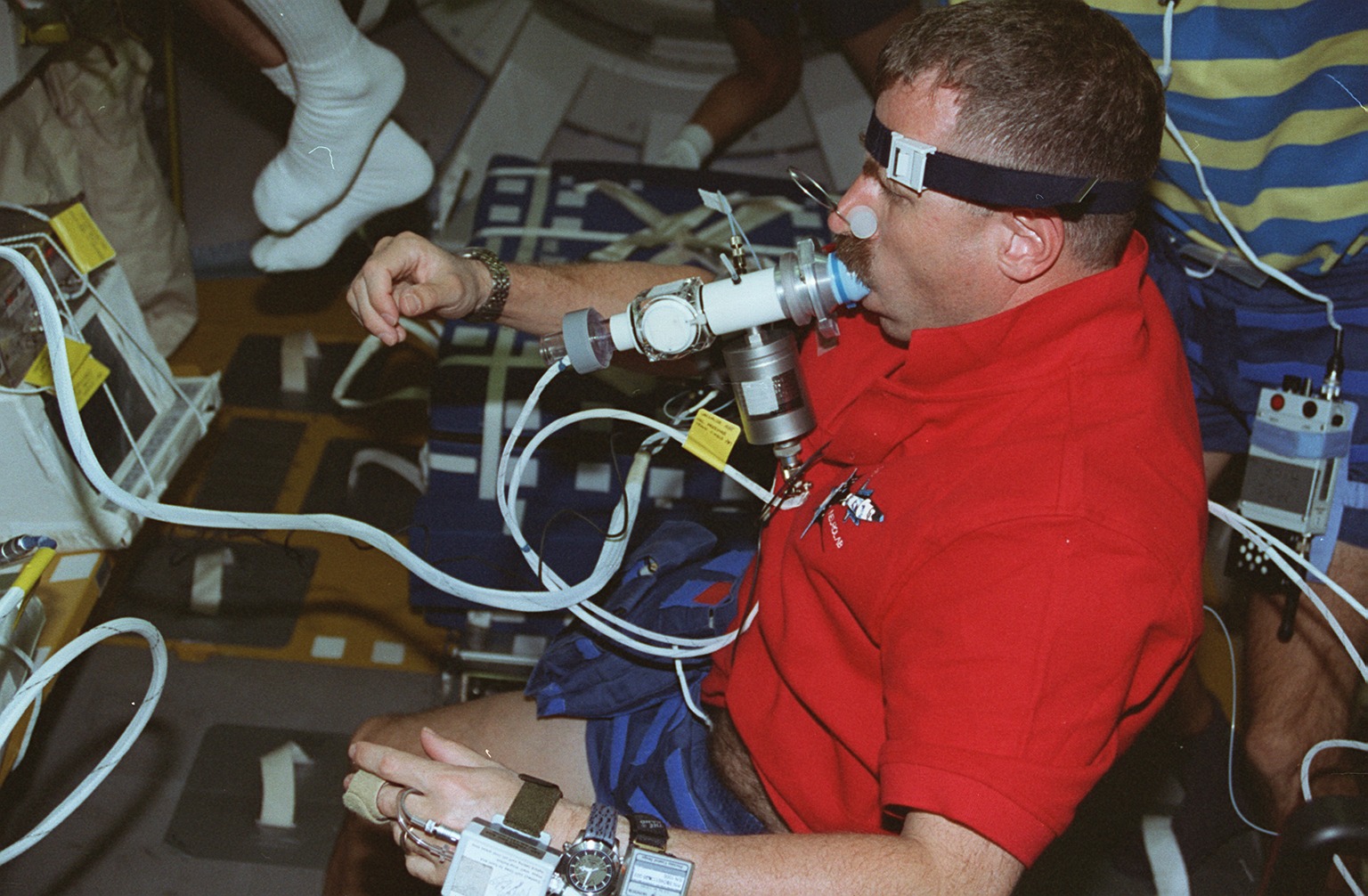

My first mission was a dedicated research flight looking at how the brain adapted to being in space. And arguably we tried to capture some of the interesting aspects of what we learned on Neurolab in the book, "Why Am I Taller?" And then my second flight was to help build the International Space Station. So I did three spacewalks helping build the station. I can definitely tell you when you go outside in the vacuum of space and you're looking at this compelling view of our planet, cast against the black infinite void of space, it gets your attention, which of course is 'astro-speak' for "you're scared to death the first time you do it."

Space.com: What's something that might surprise people about the medical effects the body experiences in space?

Williams: It's actually a bit of a problem in working in a pressurized suit. Why is that? It's a problem in the sense that when you're out there, and you're working continuously in a pressurized suit, the natural position of the human hand, outside of the suit, is kind of with your fingers flexed, but the suit extends your fingers all the way. So you're always contracting your fingers against resistance, the force of the suit, and that lifts your nail up from the nail bed. And it also separates the layers of the keratin which make up your fingernail. And the risk — it's not particularly painful, it's disfiguring — but the risk is that you get a fungal infection in there.

And having something like that when you're on a spacewalk or in your fingernails is problematic because you're obviously there to do more than one spacewalk. And when we're going back to the moon, and you're going to be working in a lunar habitat, and every time you need to go outside, you've got to put a spacesuit on. If you get that early in the mission, it's going to be problematic for the duration of the mission.

Elizabeth Howell: So, Marc Garneau was the first Canadian to fly in space in '84 on STS 41-G. And when he was going up there, one of the things that he noticed was that he had a slight tendency to sickness on Earth if his vestibular system was disturbed, but then he got up there, and he wasn't seeing the same problems. And it's just really weird, because some astronauts really react up there and not on the ground. And for some it's vice versa.

Space.com: Why is this book important at this moment in spaceflight history?

Howell: I think the reason that it's important at this moment is we're just about to be embarking on the Artemis missions. And what's really interesting about those is that we're going back to a place that we don't really know a lot about in terms of how the human body behaves, because we've had 20 years of straight experience on the International Space Station, not to mention the numerous space stations and space missions that came before that.

We now maybe might be able to stay for longer; we'll have more kinds of people in space. And we're also going to have more advanced measurements than what was available back in the 1960s and 1970s. And so it was nice to get a book out now, talking about the state of the art, particularly focusing on the International Space Station.

Williams: The whole idea of living on space stations was certainly something that was thought about in the 1960s. So along the theme of turning science fiction into science fact, I think it's quite likely that the human species in this millennium will become a spacefaring species. And all the challenges you've talked about, yeah, we're designed to live on this planet. And arguably the best planet to live on in the solar system is the one we're currently on. So we shouldn't really mess it up. Having said that, though, I think it's partly in human nature to explore, and humans will become a spacefaring species; we'll see humans living on the moon. And we'll see humans living on Mars. I'm not sure about Mars in my lifetime, but certainly within the next 100 years.

And of course, those missions, roughly speaking, three years — you know, six months, or six months back, about one Mars year, which is two Earth years, on the surface. [...] Those are going to be very compelling exploration-class missions, where the crew has to develop autonomy to live and work and thrive in those areas. And we really do have to solve the problem of radiation shielding, and how do we get there faster? And how do we keep the crew healthy, when they're transiting in that zero G phase? And then giving them the tools they need to work and thrive on the surface of Mars? It's incredible.

It's not just about the changes in the muscles and the lungs and the heart and the bone and the vestibular, all of those happen. But how do we optimize the ability of the human body to be able to make that transition to zero-G, thrive in zero-G, transition to one-sixth-G, or 40% G on Mars, and then transition back to zero-G?

And that, I think, is a really interesting question for space medicine practitioners, because we've developed these countermeasures and arguably, you know, the exercise devices that we have on the space station are great, but that's on a space station. And if you're in a zero G flight to Mars, which you know, guesstimated around six months or so, you're not going to have room for all that stuff. So what are we gonna do? And there are a lot of questions that we need to think about along those lines in terms of vehicle design, spacecraft design, different modalities, to be able to maintain muscle strength, bone density, or do something totally out of the box and hibernate all the way there and reduce the amount of bone loss and muscle wasting because we're hibernating.

Howell: And the choice that we have is how far we want to push that envelope, how far we want to be bringing folks out without having the safety net to bring them back. [...] Because that's another question too, like, how far do we want to push that risk? What do we think is acceptable versus what is not?

You can look at things like bed-rest studies, because if you have a person on the ground in that head-down position for about a week, or you know, a month, you can simulate a lot of the same problems they find in space. And so we're making good progress. It's not like we're at zero, but it's just interesting how incremental medicine is and how long it takes to solve what you think would be even a simple issue.

Space.com: Dave, are the health risks associated with the burgeoning space tourism industry acceptable from your perspective as a space medicine specialist?

Williams: The bottom line is, we approved Senator [John] Glenn when he flew in space at age 77, and did an absolutely incredible job, and really demonstrated to the world that these very rigorous criteria that we have for professional career astronauts can be changed and that other people can fly in space. And that we can broaden the accessibility to space by changing the medical requirements to be able to fly. And oh, we're not doing that in a way that increases risk. We're essentially learning more based on experience.

Space.com: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

Howell: I hope that they find some use for their own lives. Because I think that when it comes to talking about remote environments, or when you're talking about being a senior, or other applications that are similar, you can find a lot of things that are somewhat the same, because when you go up there, as a person, and you spend a week or a couple or you know, maybe a month or more, you temporarily turn into a different kind of a person, you come back and now you've got disabilities. Now you've got balance issues, your bones and your muscles are weaker for all the things that we do. And so it would be simplistic to say that you turn into a senior, but you're kind of along that road, right? You're coming back and you're suddenly a more vulnerable and weaker person than it used to be when you arrived.

Space.com: Dave, what would you tell someone who is going to space for the first time?

Williams: Bring music that is your favorite music, and make sure that you find enough time in the timeline to spend looking out the window to enjoy the view. Those are the moments that are remarkable.

"Why Am I Taller?" from ECW Press is now available.

Follow Brett on Twitter at @bretttingley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Brett is curious about emerging aerospace technologies, alternative launch concepts, military space developments and uncrewed aircraft systems. Brett's work has appeared on Scientific American, The War Zone, Popular Science, the History Channel, Science Discovery and more. Brett has degrees from Clemson University and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. In his free time, Brett enjoys skywatching throughout the dark skies of the Appalachian mountains.