How to see Uranus in the night sky (without a telescope) this week

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Just how many planets are visible without a telescope? Not including our own planet, most people will answer "five" (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn).

Those are the five brightest planets, but in reality, there is a sixth planet that can be glimpsed without the aid of either a telescope or binoculars.

That sixth planet is the planet Uranus. This week will be a fine time to try and seek it out, especially since it is now favorably placed for viewing in our late-evening sky and the bright moon is out of the way.

Article continues belowRelated: Photos of Uranus, the tilted giant planet

Of course, you'll have to know exactly where to look for it. Astronomers measure the brightness of objects in the night sky as magnitude. Smaller numbers indicate brighter objects, with negative numbers denoting exceptionally bright objects. But Uranus is currently shining at magnitude +5.7, relatively dim on the scale; barely visible by a keen naked eye on very dark, clear nights.

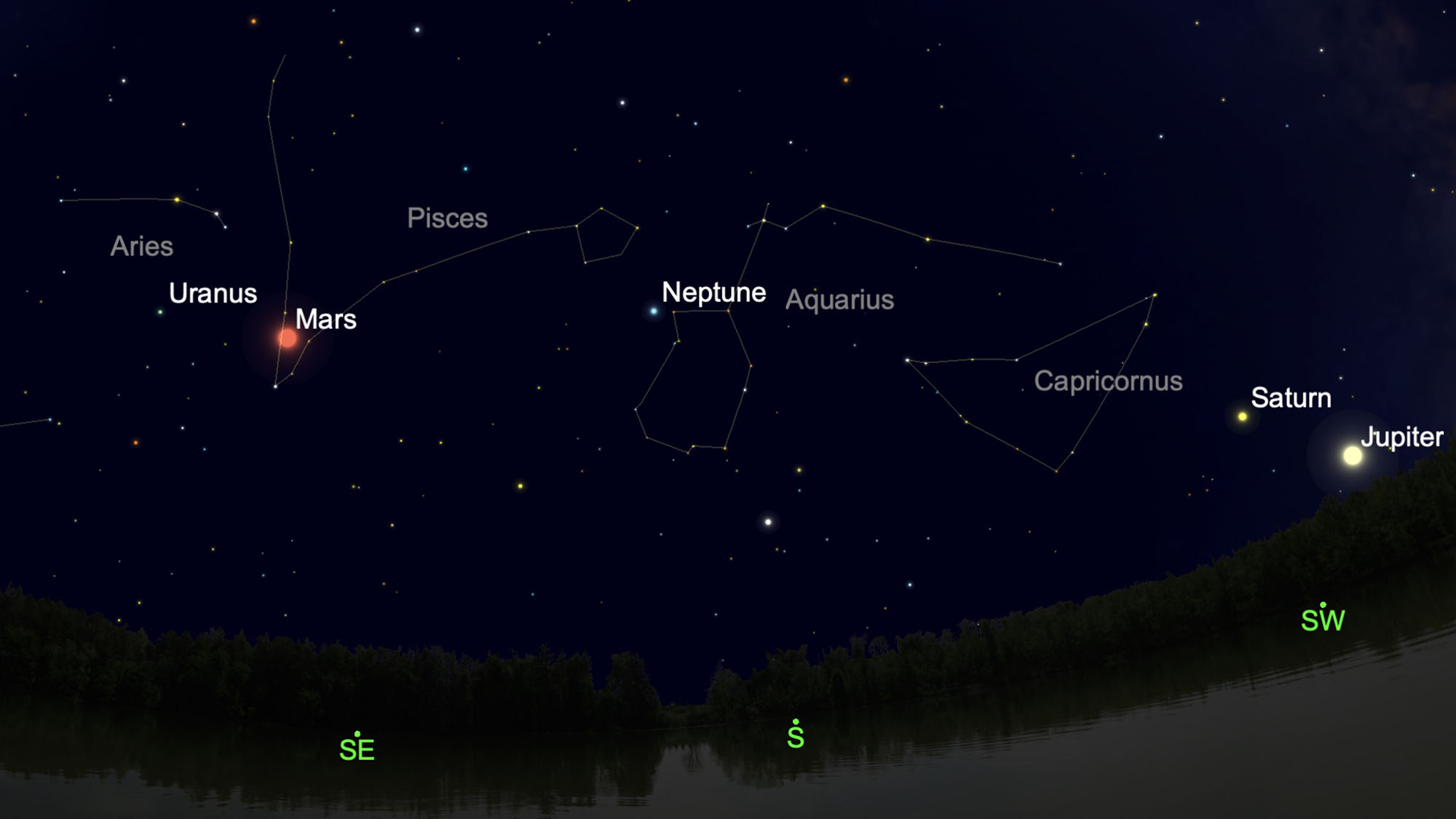

It is currently located within the constellation of Aries, the Ram, about a dozen degrees to the east (left) of the brilliant planet Mars. It's already one-third up from the eastern horizon by 11:30 p.m. local daylight time and will reach its highest point — more than two thirds up from the southern horizon — just before 4 a.m.

It is best to study the accompanying chart first, then scan that region with binoculars. Using a magnification of 150-power with a telescope of at least three-inch aperture, you should be able to resolve it into a tiny, blue-green featureless disk.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

An icy, cold world

This week Uranus is about 1.771 billion miles (2.851 billion kilometers) from Earth (only Neptune is farther away). It takes 84.4 years to orbit the sun. The planet has a diameter of about 31,518 miles (50,724 km), making it the third-largest planet, and according to flyby magnetic data from Voyager 2 in 1986, has a rotation period of 17.23 hours.

At last count, Uranus has 27 moons, all in orbits lying in the planet's equator in which there is also a complex of nine narrow, nearly opaque rings, which were discovered in 1978.

Uranus likely has an icy, rocky core, surrounded by a liquid mantle of water, methane and ammonia, encased in an atmosphere of hydrogen and helium. In fact, Uranus has the coldest atmosphere of any planet in the solar system with a minimum temperature

of -371 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 224 degrees Celsius).

A freakish tilt

A bizarre feature is how far over Uranus is tipped. The other planets are tilted somewhere between 3 degrees and 29 degrees, but Uranus' north pole lies 98 degrees from being directly up and down to its orbit plane.

From our point of view, this means that sometimes we see Uranus with its north pole pointing at us. At other times we see it with its equatorial belt oriented vertically instead of horizontally. From the point of view of a hypothetical astronaut visiting Uranus, daylight and darkness would be nothing short of extraordinary. Its seasons are extreme: when the sun rises (as an example) at the north pole, it stays up for 42 Earth years; then it sets and the north pole is in darkness for 42 Earth years.

Accidental discovery

In the late winter of 1781, British astronomer Sir William Herschel had just finished building a new 6.3-inch (16 centimeters) reflecting telescope and began to study the stars through it. On the night of March 13, he had his telescope turned on the constellation of Gemini, the twins. There, to his great surprise, he came across an extra star that was not plotted on any of his star charts. An accomplished astronomer, Herschel was quick to realize that what he found could not possibly be a star, for it appeared in his telescope as a glowing disk as opposed to a twinkling speck of light.

Continuing his observations of this unusual object night after night, Herschel soon perceived movement; it was slowly shifting its position among the background stars of Gemini. Finally, he decided that he had discovered a new comet and he wrote up a detailed report of his observations, which were published on April 26.

The report of a new comet excited astronomers all over Europe, and they all eagerly trained their telescopes on Herschel's discovery. King George III, who loved the sciences, had the astronomer brought to him and presented him with a life pension and a residence at Slough, in the neighborhood of Windsor Castle.

Multiple monikers

Soon, enough observations were made to calculate an orbit for Herschel's "comet." That's when an increasing number of astronomers began to doubt that what they were looking at was really a comet. For one thing, it seemed to be following a nearly circular orbit out beyond Saturn.

Eventually it was determined that Herschel's "comet" was in fact a new planet. For a while, it actually bore Herschel's name, though Herschel himself proposed the name Georgium Sidus — "The Star of George," after his generous benefactor. However, the custom for a mythological name ultimately prevailed and the new planet was finally christened Uranus.

Related: Who discovered Uranus (and how do you pronounce it)?

Prior to its discovery, the outermost planet was considered to be Saturn, named for the ancient god of time and destiny. But Uranus was the grandfather of Jupiter and father of Saturn and considered the most ancient deity of all.

It probably was for all for the best. After all, if Herschel's request was granted, just think of how we might have listed the planets in order from the sun: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and ... George?

And then came Neptune

Interestingly, it was Uranus that led astronomers, 65 years later, to Neptune, fourth and last of the giant planets. It's a fascinating story and came about this way:

By plotting the path of a planet, astronomers can draw up a table (called an "ephemeris") that can show them exactly where the planet will be at any given time. So, after the discovery of Uranus, they set about determining an ephemeris for it.

But this method didn't seem to work; sometimes Uranus turned up ahead of its predicted position; sometimes it lagged behind. It seemed to astronomers that some unknown body was somehow perturbing Uranus's orbit.

In 1846, two astronomers, Urbain J.J. Leverrier (1811-1877) of France and John Couch Adams (1819-1892) of England independently were working on this very problem. Neither knew what the other was doing, but ultimately, both men had figured out the probable path of the supposed object that was disturbing the orbit of Uranus. Both believed that the unseen body was then in the constellation of Aquarius.

Adams was a student at Cambridge University, and he sent his results to Sir George Airy (1801-1892), the Astronomer Royal, with specific instructions on where to look for it. For some unknown reason Airy delayed a year before starting the search. In the meantime, Leverrier wrote to the Berlin Observatory requesting that they search in the place he directed. Johann Galle and Heinrich d'Arrest at Berlin did exactly as instructed and found the new planet in less than an hour.

The naming of this new eighth planet was more complicated than for Uranus. Initially, Janus and Oceanus were suggested. Leverrier wanted it to be named after him. But while the population of France seemed in favor of this, the other European countries resisted this moniker. Eventually, it was named for Neptune after the god of the sea.

Ice giant

Neptune is slightly smaller than Uranus, measuring 30,599 miles (49,244 km) in diameter. Like Uranus, Neptune is a frigid world, with temperatures at its cloud tops of -361 degrees F (-218 C). Because they are similar both in size and temperatures, Uranus and Neptune are referred to as "ice giants."

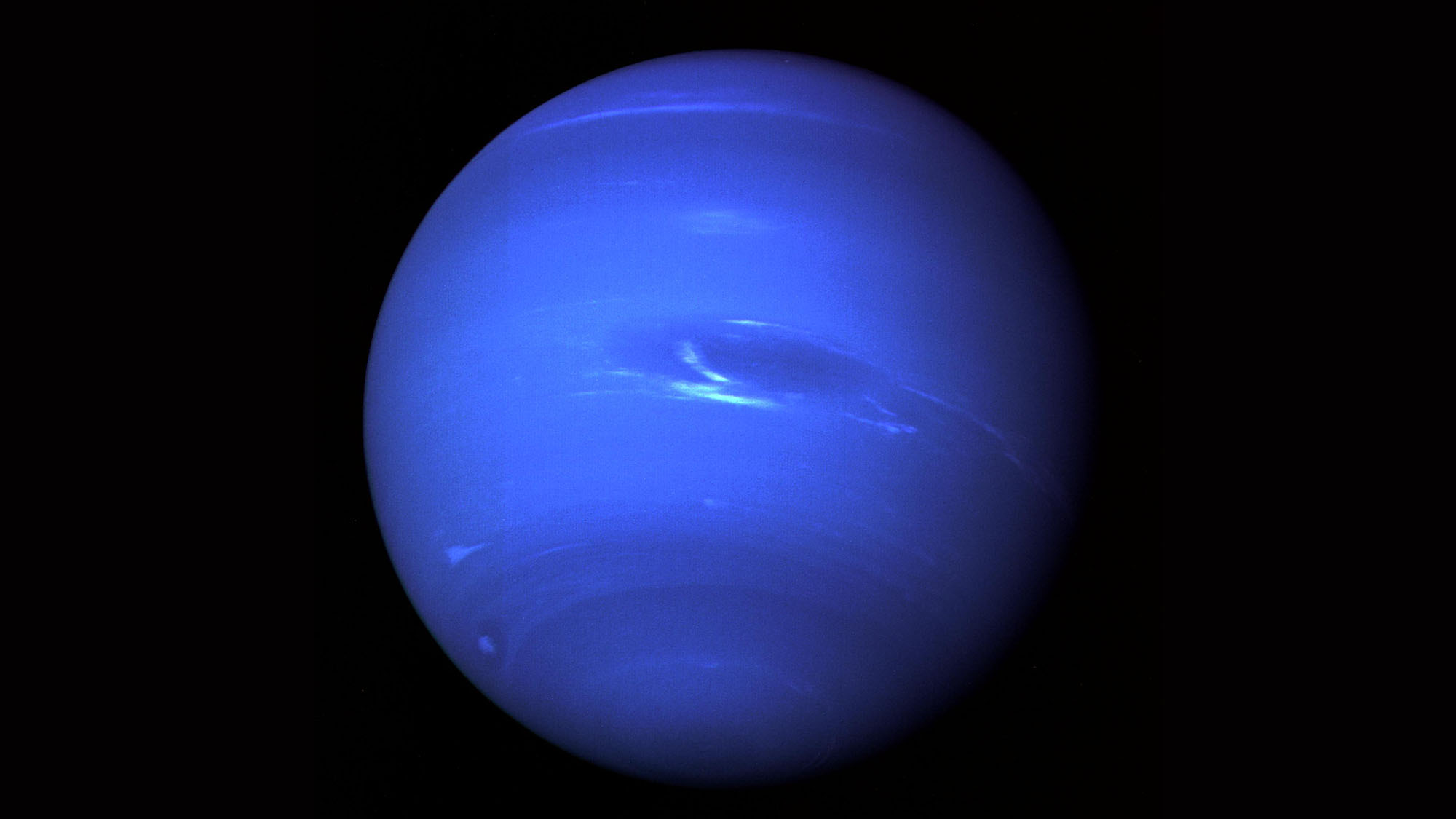

Voyager 2 passed Neptune in 1989 and showed it to possess a deep-blue atmosphere, primarily composed of hydrogen, helium and methane with rapidly moving wisps of white clouds as well as a Great Dark Spot, rather similar in nature to Jupiter's famous Great Red Spot.

Related: Photos of Neptune, the mysterious blue planet

Because of its gaseous composition, its speed of rotation varies from 18 hours at the equator to just 12 hours at the poles. This differential rotation is the most pronounced of any other planet and results in exceedingly strong winds reaching speeds upward to 1,300 mph (2,200 kph). Most of the winds on Neptune move in a direction opposite to the planet's rotation.

Voyager 2 also revealed the existence of at least three rings around Neptune, composed of very fine particles. Neptune has 14 moons, one of which, Triton has a tenuous atmosphere of nitrogen and at nearly 1,700 miles (2,700 km) in diameter, is larger than Pluto.

Finding Neptune

Unlike Uranus, Neptune is much too faint to be viewed with the unaided eye, lying at a mean distance from the sun of 2.8 billion miles (4.5 billion km); the most distant planet. It's about seven times dimmer than Uranus, but if you have access to a dark, clear sky and carefully examine the map above, you should have no trouble in finding it with a good pair of binoculars.

September is Neptune's month. It will be at opposition to the sun on Sept. 11, so it will be in the sky all night long, reaching its highest point in the southern sky at around 1 a.m. local time. Neptune can currently be found among the stars of Aquarius, the water bearer.

With a telescope, trying to resolve Neptune into a disk will be more difficult than it is with Uranus. You're going to need at least a 4-inch (10 cm) telescope with a magnification of no less than 200-power, just to turn Neptune into a tiny blue dot of light.

Cases of mistaken identity

Lastly, in deference to Herschel and Leverrier, they are not the first discoverers of Uranus and Neptune. Uranus may have been first charted (mistakenly) as far back as 128 B.C. by the Greek astronomer and mathematician Hipparchus of Nicaea, including it as a faint star in his catalogue. In 1690, the English astronomer John Flamsteed catalogued Uranus as the star 34 Tauri, and the French astronomer Pierre Charles Le Monnier saw it no less than twelve times between 1750 and 1769, never realizing that what he was looking at was not a star but a new planet.

And Neptune was very nearly discovered by none other than the renowned Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei with his crude telescope. Galileo unknowingly recorded Neptune as an eighth-magnitude star while observing Jupiter and its system of four large satellites on Dec. 28, 1612 and again on Jan. 27, 1613. If he had only continued to keep watch in the following nights, he would have almost certainly would have realized that one of the background stars was moving.

He would have then discovered the eighth planet almost 170 years before the discovery of the seventh!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.