SpaceIL's Beresheet Lunar Lander: Israel's 1st Trip to the Moon

Reference Article

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

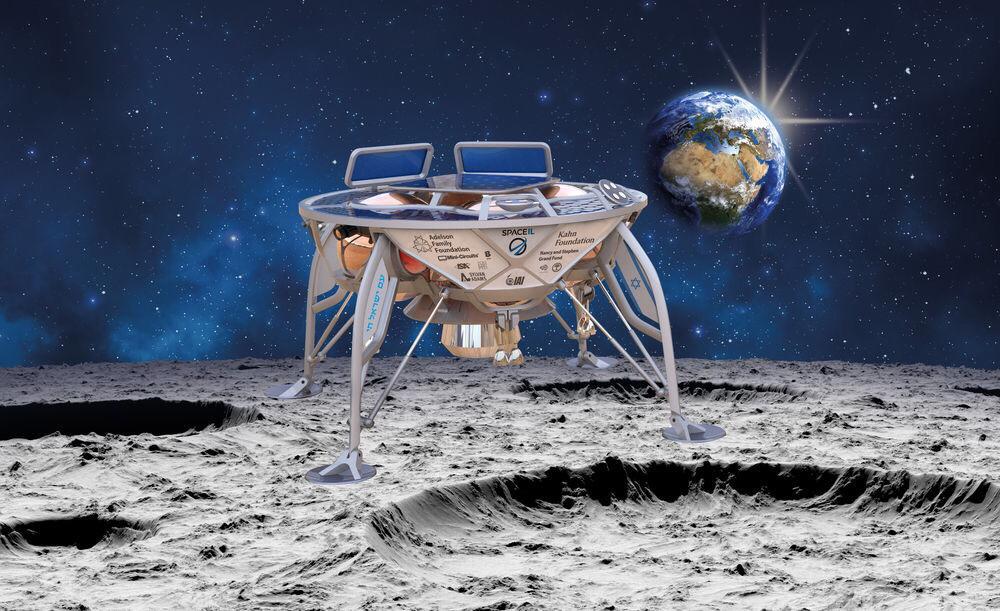

Some nights, the moon may look close enough to touch, but only a handful of teams have succeeded in reaching the lunar surface. The USSR did it in 1966 and the U.S. followed just four months later. China pulled it off in 2013 and again just recently, in January 2019. In April 2019, an Israeli nonprofit organization called SpaceIL tried to become the first Israeli entity to land a spacecraft on the surface of the moon, but it failed to stick the landing.

Israel and SpaceIL aren't throwing in the towel just yet. Just days after the failed attempt, Morris Kahn, the billionaire businessman, philanthropist and SpaceIL president, confirmed that the SpaceIL team had already scheduled meetings to begin planning the Beresheet 2.0 mission.

"We're going to actually build a new halalit — a new spacecraft," Kahn said in a video statement posted on Twitter by SpaceIL. "We're going to put it on the moon, and we're going to complete the mission."

SpaceIL's lunar lander, Beresheet, launched from Cape Canaveral on a used SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket on Feb. 21, 2019, along with an Indonesian communications satellite and a U.S. Air Force satellite. Over nearly two months, the craft maneuvered into successively longer loops around the planet until reached the moon. Beresheet carried a time capsule of digital records and an instrument to study the moon's magnetic field. Although the spacecraft failed to touch down safely, it was the first attempted moon landing for Israel and the first for a privately funded organization from anywhere.

While previous moonshots culminated from years of concerted governmental effort, SpaceIL operates more like a startup company. Inspired by the Google Lunar X Prize, an international competition to land a probe on the moon, computer engineer Yariv Bash launched the endeavor in 2010. Bash started with a web domain and a Facebook post asking, "Who wants to go to the moon," according to SpaceIL educational volunteers manager Hili Shapiro.

Initially, Bash and his two co-founders hoped to land a water bottle-size probe on the moon by the end of 2012 to win the $20 million purse. In addition to research, the team's early efforts focused on securing funding and finding rocket scientists. "You can't build a spacecraft with only three people," Shapiro told Space.com.

Over the course of the project, SpaceIL managed to raise at least $100 million from major donors and recruit scores of volunteers; Shapiro estimates that roughly 80 percent of the nearly 200-person organization consists of volunteers, including some engineers.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

After building the company, SpaceIL had to build the spacecraft. Engineering began in earnest after the team secured a launch contract with SpaceX in 2015 and determined how much volume would be available on the rocket. And it wasn't a lot.

To keep costs low, SpaceIL agreed to share a rocket with two other satellites. The shared launch would bring the craft only to Earth orbit, from which point the lunar lander would have to fly itself all the way to the moon. The added fuel requirements of this approach killed plans for the water-bottle-size probe, so blueprints for a 1,314-lb. (596 kilograms), smart-car-size, four-legged lander took their place. [Israel's 1st Moon Lander: The SpaceIL Beresheet Lunar Mission in Pictures]

The cramped rocket didn't allow room for Beresheet to include backup systems, such as an extra computer to test code or run updates. Any major system failure would doom the craft, according to flight software developer Shai Yehezkel; however, mission control made minor tweaks to adapt on the fly, such as configuring the craft to reject faulty star readings that unexpectedly cropped up when Earth blocked part of the craft's field of view. "The best engineering work was made from the limited budget," Yehezkel told Space.com. "We know how to improvise."

The X Prize expired unclaimed in 2018, but SpaceIL's outreach-driven mission has kept the company going. Shapiro estimates that the company's volunteers lecture 20,000 students each month, and cereal boxes across Israel recently featured cardboard cutouts of Beresheet, which means "in the beginning," or "genesis," in Hebrew.

"We are not just saying to dream big," Shapiro said. "We are actually showing them that we are doing it."

Beresheet made three orbits around Earth, each longer than the last, until the craft crossed paths with the moon. The original goal was to loop around the moon twice before touching down in the Mare Serenitatis, or Sea of Serenity, on April 11, 2019, at the end of a two-week long lunar night, the flight team expected. The early morning light of the subsequent two-week lunar day gave the probe the energy it needed to record the local magnetic field, an experiment run in collaboration with NASA.

But even it had landed successfully, the same sunlight would have soon spelled Beresheet's demise, overheating the lander's electronics. Now, the vehicle has become a monument. It's also an archive, as it carried a DVD-sized digital-analog hybrid disks bearing copies of the Bible, drawings from Israeli schoolchildren, English Wikipedia and 30 million pages of records representing a "backup" of humanity's knowledge. SpaceIL hopes future moonwalkers might decode the time capsule and learn about Earth in 2019. "We are throwing them a challenge," Yehezkel said.

Despite Beresheet's disappointing crash-landing, the SpaceIL team remains dedicated to their goal of successfully landing an Israeli spacecraft on the moon.

Israel Aerospace Industries, the contractor who built the craft, has signed an agreement with a German firm to build similar landers for the European Space Agency in the future.

SpaceIL plans to continue its educational activities and seeks an Israeli "Apollo effect" to inspire the next generation of space enthusiasts, Shapiro said. "We hope our story will begin more stories."

Additional resources:

- Watch an animation of Beresheet's flight path, from SpaceIL.

- Read more about Beresheet's science mission, from NASA Science Solar System Exploration.

- Watch a video summarizing SpaceIL's mission, from the company.

This article was updated April 15, 2019 by Space.com Reference Editor Kimberly Hickok.

Charlie Wood is a freelance journalist covering physical sciences both on and off this pale blue dot. He contributes to Space.com and LiveScience, as well as Popular Science, Scientific American, Quanta Magazine, and others. These days he writes from New York but in previous lives he taught physics in Mozambique and science English in Japan. Find him on Twitter @walkingthedot.