Why Does Enceladus Have an Underground Ocean? New Research Probes Differences Between Saturn's Moons

Enceladus' hidden ocean sets it apart from the pack — but why?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

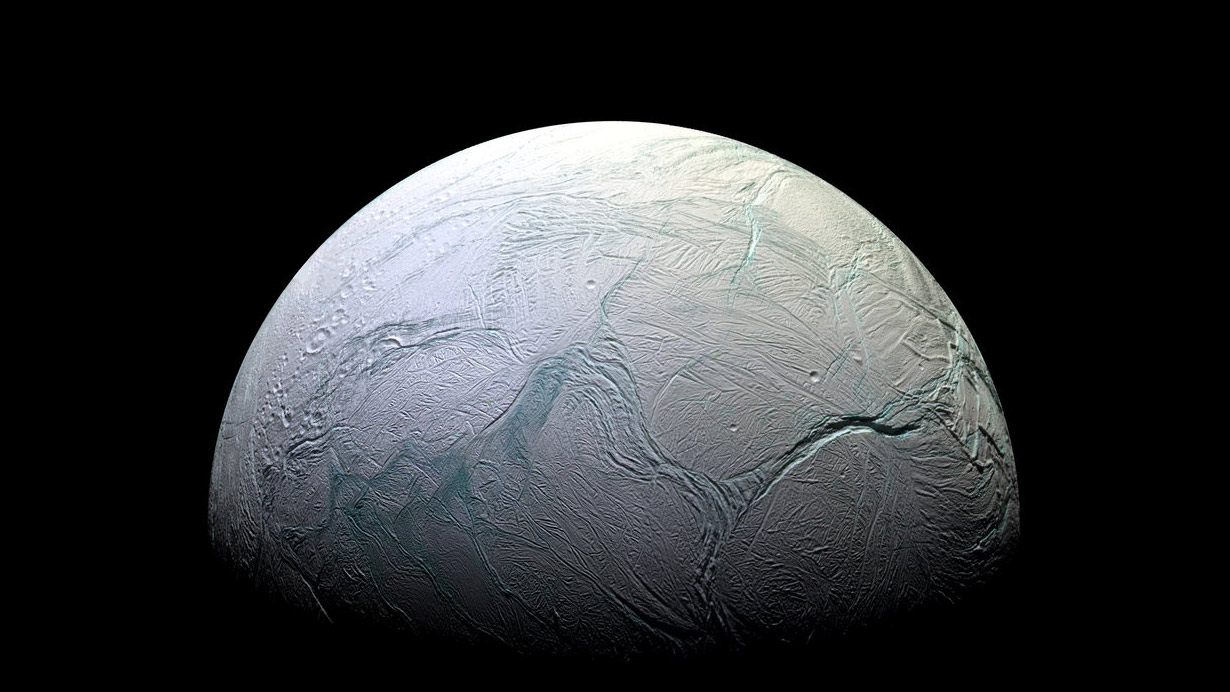

New answers for mysteries concerning Saturn's moons could shed light on whether one, Enceladus, could support life, researchers say. For example, researchers may now know why Enceladus harbors a hidden ocean while many of its siblings do not.

Saturn not only has extraordinary rings, but it also boasts more than 60 moons. These natural satellites range in size from tiny moonlets less than 1000 feet (300 meters) wide to the enormous Titan, which is larger in diameter than the planet Mercury. Many of these moons orbit far from the ringed planet, but others are embedded within the rings.

Much has remained a mystery about the origins and evolution of Saturn's larger innermost moons: Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione and Rhea (listed in order of increasing diameter, mass and distance from the planet). Scientists had expected the densities and structures of these moons to depend on their mass or distance from Saturn, but spacecraft analyzing them have unexpectedly proven that this is not the case.

Related: Saturn Moon Enceladus Is First Alien 'Water World' with Complex Organics

Previous research suggested that these moons coalesced from rings of debris around Saturn. According to this idea, the gravitational pull from the planet would cause powerful tides on these moons that would result in churning and melting, forces that would lead heavier rock to sink into the moons' cores and lighter ice to dominate their shells. Such tidal effects would prove stronger when the moons were closer to the planet and weaker as they moved farther away over time.

Mimas shows no geological activity, even though it is the innermost of these five moons and thus subject to the strongest tides from Saturn. In contrast, Enceladus is farther from Saturn and experiences 30 times weaker tides than Mimas. However, somehow tidal forces melt ice within this moon's interior, leading to a giant underground ocean and "cryovolcanoes" that spew water.

Furthermore, Rhea is the largest moon and thus the one most likely to retain heat that would help melt its rock and ice and separate its interior into layers, but prior work suggested that this moon may be a mixed jumble of rock and ice. In contrast, Mimas, Enceladus and Dione, which are smaller than Rhea, do have structures of rocky cores and icy shells.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Understanding more about the origins of the geological activity of these moons could help answer questions such as whether Enceladus' hidden ocean could support life. "Fundamentally, what excites me is the search for life beyond Earth," study lead author Marc Neveu, a planetary scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center at Greenbelt, Maryland, told Space.com.

To solve the puzzles these moons pose, scientists would like to model the effects of tides on the moons' geology. However, simulations of the orbits that cause tides operate on daily scales, whereas simulations of geology typically operate on scales of millions of years. So, prior work generally chose one approach or the other, modeling tides or modeling geology.

In the new study, however, researchers designed computer models that simulated both the geological changes and simplified orbital effects these moons might have experienced over Saturn's roughly 4.5-billion-year life.

The scientists found that tidal forces would lead to enough geological activity for past or present oceans to exist in the interiors of Enceladus, Tethys and Dione. Enceladus likely still has an underground ocean, because its gravitational interactions with other moons such as Tethys and Dione keep its orbit relatively oblong. And the resulting continual variation in the strength of the gravitational pull from Saturn regularly alters the level of distortion of Enceladus' shape, flexing and heating the moon's interior.

"This is the first explanation consistent with data returned from NASA's Cassini spacecraft for how a tiny moon such as Enceladus, which is only about as big as Washington state or the British Isles, has a subsurface ocean when other sibling moons that are bigger or closer to Saturn, and therefore more likely to have such oceans, do not," Neveu said.

The researchers also found that Mimas likely formed only 100 million to 1 billion years ago; if it were older, interactions between Mimas and Saturn's rings would have led that moon to a higher orbit than it currently occupies. Mimas' young age means that the moon would have formed after all the radioactive material present at the formation of the solar system about 4.6 billion years ago had already decayed. As such, its innards would have started off too cold and hard for tidal forces to heat much.

"When ice is warmer and squishier, it becomes more responsive to tidal forces that deform it," Neveu said. "Mimas lacked the minimum amount of heat to start with to get tidal forces to trigger runaway heating."

As to why Rhea's innards might not be separated into layers, "the measurements from the Cassini spacecraft of the interior of Rhea have a degree of uncertainty in them, so it's possible the deeper layers of its interior are rockier and the near-surface layers are icier," Neveu said.

All in all, these findings suggest that Enceladus' hidden ocean is about 1 billion years old. "One billion years is enough for life to emerge — 1 billion years after Earth was born, there was life," Neveu said. At the same time, "1 billion years means there may still be enough chemical activity between Enceladus' rocky core and its ocean to provide energy for any potential microbial life, similar to the chemical energy in Earth's seafloor that helps sustain ecosystems there. Enceladus' ocean is not too young and not too old. It may be just the right age for life."

Neveu cautioned that a key limitation of this research was that it made simplifications that could have affected its accuracy. "We didn't compute the high tides and low tides that each of the five moons experienced at the same time every few hours for 4.5 billion years — to do that right, it would take about 20 years on a desktop computer," he said.

In the future, the scientists want to simulate more-complex scenarios, incorporating more features about Saturn and its satellites, such as how the planet may have gained moons that got hurled away or that collided with other moons, Neveu said.

The scientists detailed their findings online April 1 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

- Weirdly Colored Saturn Moons Linked to Ring Features, NASA's Cassini Revealed

- Cassini's 13 Greatest Discoveries During Its 13 Years at Saturn

- Enceladus: Saturn's Tiny, Shiny Moon

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us