Here's where planetary science is going in the next decade

Get excited about Uranus (and so much more).

The solar system is overflowing with fascinating destinations, but NASA can only operate so many missions.

So every 10 years, the agency asks scientists to evaluate the state of planetary science and determine what questions should be the top priorities for the scientific community. Led by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, this massive undertaking is dubbed a decadal survey — and the latest such report is now public, offering a tantalizing look at what space enthusiasts can look forward to in the next decade.

"This report sets out an ambitious but practicable vision for advancing the frontiers of planetary science, astrobiology, and planetary defense in the next decade," Robin Canup, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute and co-chair of the steering committee for the decadal survey, said in a statement. "This recommended portfolio of missions, high-priority research activities, and technology development will produce transformative advances in human knowledge and understanding about the origin and evolution of the solar system, and of life and the habitability of other bodies beyond Earth."

Committee members will speak about the report during a news conference being held on Tuesday (April 19) at 2 p.m. EDT (1800 GMT), which you can watch live via the National Academy.

Related: Our solar system: A photo tour of the planets

Scientists began working on this new decadal survey in late 2019. The process included half a dozen committees, each meeting at least 20 times and informed by a total of 527 white papers submitted by scientists from around the world. The resulting document is 780 pages long and comes just months after the publication of a similar document for the field of astronomy and astrophysics.

The magnitude of the report means that scientists and administrators will be poring over its findings for months, but some initial takeaways from the report are clear.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Flagship missions

One key duty of the decadal survey is to prioritize missions for NASA, including the largest missions, dubbed flagships. The agency's two current flagship missions, recommended by the previous decadal survey, are the $2.7 billion Perseverance Mars rover that touched down on the Red Planet last year and the $4.25 billion Europa Clipper mission scheduled to launch in 2024.

For the new report, the committee evaluated six potential flagship projects across the solar system, ranging from a spacecraft to land on Mercury to a mission that would explore both Neptune and its largest moon, Triton.

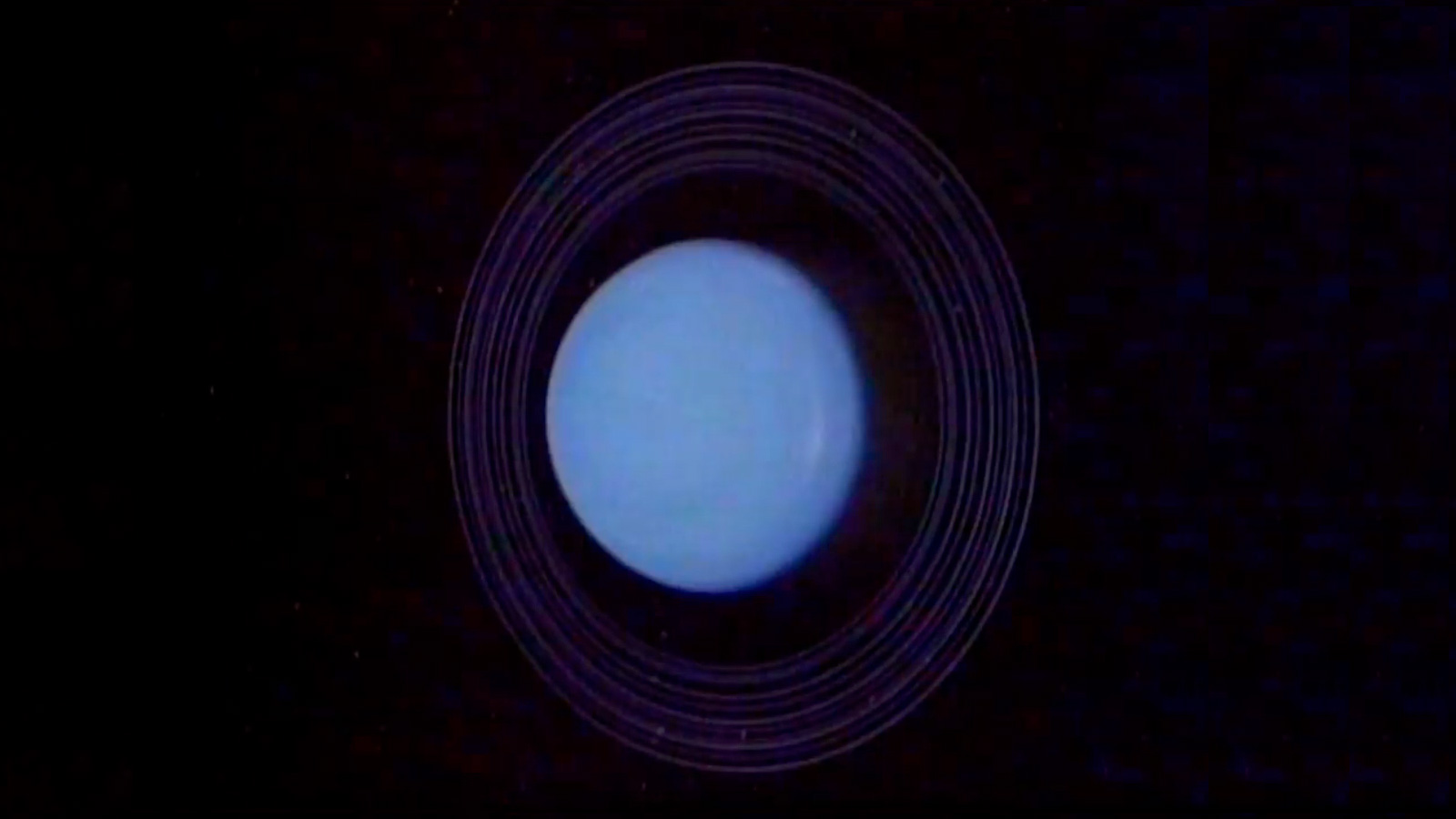

Of these proposed flagship missions, the committee determined that NASA's top priority should be developing a flagship-class mission to Uranus — what could be a $4 billion endeavor. A combination of factors pushed the concept of a Uranus orbiter and probe into first place, including both the science potential offered by finally getting a close-up look at a so-called "ice giant" and the feasibility of the mission.

The mission would launch in 2031 or 2032, spend about 13 years trekking out to its target, then orbit Uranus for several years, examining its atmosphere, interior, rings and moons.

"Uranus itself is one of the most intriguing bodies in the solar system," committee members wrote in the document. In addition, the committee emphasized that finally developing a dedicated mission to one of the ice giant planets — Uranus or its neighbor, Neptune — was a vital priority, but noted that the logistics of a Neptune mission during the years in question were challenging.

If NASA receives strong enough funding to pursue a second flagship mission before the next decadal survey is released in 2032, the committee recommended that mission be the so-called Enceladus Orbilander, a perhaps $5 billion spacecraft that would orbit and land on Saturn's small icy moon. This mission would orbit the moon for about 1.5 years, then spend two years at work on its surface, analyzing scoops of the icy material.

Planetary science at home and abroad

With eight planets, more than 200 moons and countless smaller objects rattling through the solar system, planetary scientists face a rich buffet of exploration opportunities. But a key thread running through the new decadal is considering planetary science not solely in our own celestial neighborhood, but also in the context of alien worlds.

That's not surprising: In 2012, when the last decadal was published, scientists had identified fewer than 1,000 confirmed exoplanets beyond our solar system; today, that number exceeds 5,000. In the intervening years, astronomers have also worked to understand the ways in which our solar system might be representative — or not — of other planetary systems.

In fact, exoplanet science is one key reason the decadal survey team cited for prioritizing a flagship mission to Uranus. "Exoplanets with similar masses are perhaps the most abundant class of exoplanet, and an inherently different class of planet than gas-rich Jupiter and Saturn," scientists wrote.

The decadal highlights three vast themes as the most pressing scientific questions for planetary scientists to address over the next decade: origins ("How did the solar system and Earth originate, and are systems like ours common or rare in the universe?"), worlds and processes ("How did planetary bodies evolve from their primordial states to the diverse objects seen today?") and life and habitability ("What conditions led to habitable environments and the emergence of life on Earth, and did life form elsewhere?").

These questions loom large when considering the potential destinations the committee endorsed for medium-class missions. These options include a geophysical network on the moon, sample-return missions to a comet or the dwarf planet Ceres and a variety of spacecraft bound for Saturn or its moons Titan and Enceladus.

But while the decadal survey is grounded in big-picture thinking, it also includes a clear focus on Earth. For the first time, the document includes a section on the state of the profession, evaluating social and structural issues facing planetary scientists, like implicit and systemic bias and the low representation of people from marginalized groups in the field.

Here, the committee emphasized the importance of strengthening systems for gathering and analyzing evidence about the real status of these issues. The decadal also endorsed a system called dual anonymous peer review, which scientists now use to allocate time on both the Hubble and James Webb space telescopes. The system eliminates the leading scientist's name from proposals leaving committees to award observations based solely on the science proposed.

"While scientific understanding is the primary motivation for what our community does, we must also work to boldly address issues concerning our community’s most important resource — the people who propel its planetary science and exploration missions," Philip Christensen, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University and steering committee co-chair, said. "Ensuring broad access and participation in the field is essential to maximizing scientific excellence and safeguarding the nation's continued leadership in space exploration."

A second new section covered planetary defense, a growing focus area for NASA that involves identifying, tracking and evaluating the risk to Earth posed by asteroids in our neighborhood. The agency already has in place survey programs to detect such asteroids and is working to build a new spacecraft, called NEO Surveyor, to identify such near-Earth objects, all of which the decadal endorsed.

In addition, the decadal survey calls for NASA to make use of the 2029 flyby of the large asteroid Apophis. During this encounter, the asteroid will definitely not collide with Earth, but such a close flyby of such a large asteroid offers scientists a unique opportunity to practice planetary defense and study any changes the flyby causes in the asteroid itself.

The planetary defense program launched its first dedicated mission, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) last fall; this year the spacecraft will collide with an asteroid's moon to test humans' ability to move a threatening asteroid out of Earth's danger zone. After this mission and the NEO Surveyor mission, the decadal survey notes that NASA's next priority should be to launch a rapid-response spacecraft to scout out a nearby asteroid, a sort of dress rehearsal for disaster.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.