NASA's Parker Solar Probe spotted 'stealth' outburst on the sun

Coronal mass ejections aren't known for being subtle: Each such event can fling huge amounts of the soup of charged particles called plasma off the sun and out into the solar system.

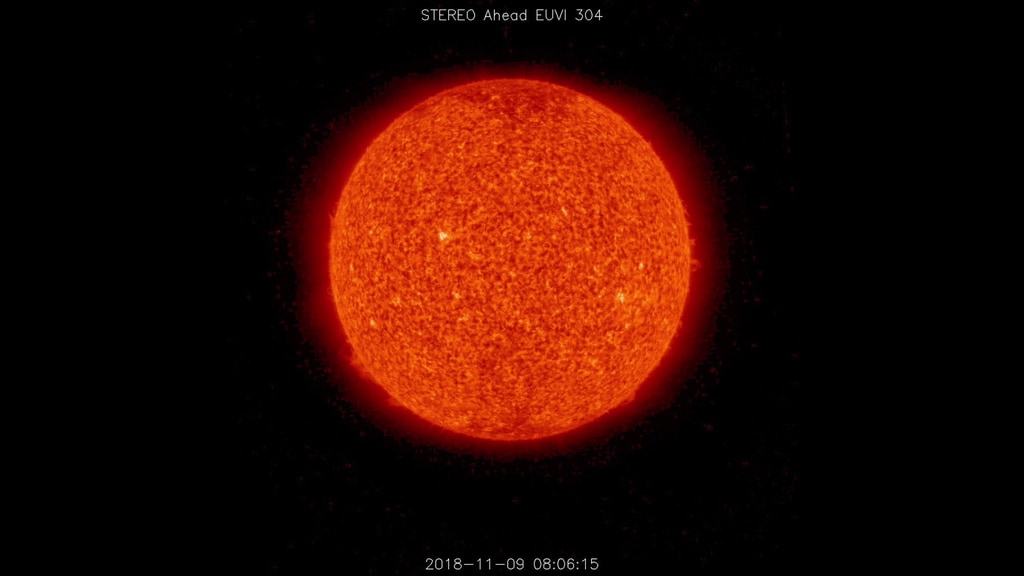

In November 2018, as seen from Earth and certain spacecraft, the sun seemed to be calm. But it wasn't: The sun was experiencing what scientists call a "stealth" coronal mass ejection. And conveniently, NASA's Parker Solar Probe was completing its first close pass behind the sun, putting its instruments in a perfect position to see what was happening on Nov. 11 and 12 during this usually cryptic event.

"If you've ever seen a coronal mass ejection image, you normally see a lot of activity in these images," Kelly Korreck, a solar physicist at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, said during a presentation last month at the 235th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Honolulu. "You would see a large blowout, you would probably see one of these exploding. But as you saw in this video, there wasn't much there."

Related: See the sun flip out in wild new satellite view

Even in some of the Parker Solar Probe data, it wasn't obvious at first what was happening during the incident, Korreck said. "When we looked at this initially, just the thermal data, we didn't necessarily think that there was a coronal mass ejection there," she said.

But other observations targeting energetic particles did include the fingerprint of a shock, a phenomenon that usually accompanies a coronal mass ejection. Scientists could also confirm the probe was flying through a coronal mass ejection based on data its instruments were gathering about the magnetic field.

The Parker Solar Probe is flying closer to the sun than any spacecraft ever has, which means it can study coronal mass ejections earlier in their development than other probes can. That means scientists hope the probe's data could help better pinpoint where on the sun an individual coronal mass ejection is born.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But just seeing a stealth coronal mass ejection is a step in the right direction, according to Korreck. "They're something that we're not traditionally able to see in the ways that we've previously detected coronal mass ejections," she said. "We're starting to see hints of them with better and better telescope resolution. However, at the same time, we've kind of reached the end where we actually have to go in situ to do a better measurement." And there's nothing more in situ than Parker Solar Probe.

Within our solar system, coronal mass ejections are important because they can interfere with communications and navigation satellites orbiting Earth. And the farther astronauts venture from Earth, the more vulnerable they will be to the potential health impacts of such blasts. That's when learning to see coronal mass ejections we currently miss would become particularly important.

Such phenomena are also intriguing because our sun is a star like any other. Scientists have spotted coronal mass ejections produced by other stars, but they'll never be able to see all such distant events.

"This is another class that definitely can't be seen on other stars," Korreck said. "Is there a way that we can do this with Parker [Solar Probe] to better understand what's going on in other star systems?"

- NASA's Parker Solar Probe mission to the sun in pictures

- What's inside the sun? A star tour from the inside out

- NASA sun probe spies the solar wind in 1st birthday photo

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.

-

rod ReplyAdmin said:Coronal mass ejections aren't known for being subtle: Each such event can fling huge amounts of the soup of charged particles called plasma off the sun and out into the solar system.

NASA's Parker Solar Probe spotted 'stealth' outburst on the sun : Read more

The report here wraps up with, "Within our solar system, coronal mass ejections are important because they can interfere with communications and navigation satellites orbiting Earth. And the farther astronauts venture from Earth, the more vulnerable they will be to the potential health impacts of such blasts. That's when learning to see coronal mass ejections we currently miss would become particularly important. Such phenomena are also intriguing because our sun is a star like any other. Scientists have spotted coronal mass ejections produced by other stars, but they'll never be able to see all such distant events. "This is another class that definitely can't be seen on other stars," Korreck said. "Is there a way that we can do this with Parker to better understand what's going on in other star systems?"

Our Sun is not so similar to other stars. Quite a number are rapid rotators that exhibit large flares and likely very large CME events too. Presently the Sun rotates about 2 km/s at the equator, other stars like T Tauri or many red dwarfs, rotate fast in the area of 10-20 km/s. The Sun, 4 billion years ago was spinning some 16+ km/s. Anticipate much more energetic CME events and flares at other stars. Kepler mission did document for quite a number of stars Kepler examined. This is a problem when searching for Earth 2.0 among the more than 4,000 exoplanets documented now. The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia

Host star spin rates, CME events, and flaring. Fortunate for life on Earth today, our Sun is much more quite than many other stars.