Watch for fireballs as the Northern Taurid meteor shower peaks tonight (Nov. 12)

Skywatchers should keep their eyes peeled for potentially bright fireballs.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

On Saturday (Nov. 12) the annual Taurid meteor shower will reach its peak in the northern hemisphere.

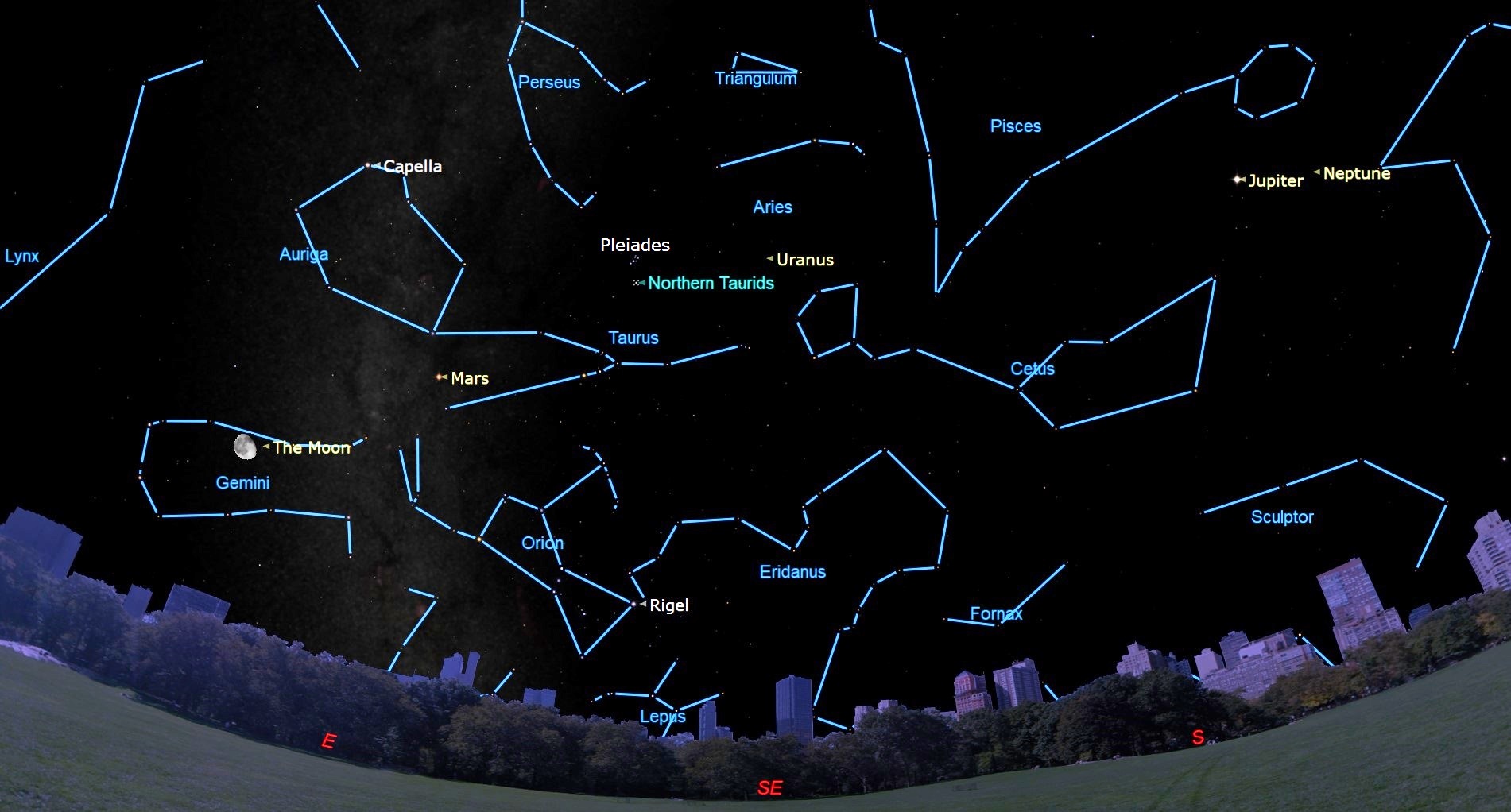

This year the Northern Taurid meteor shower lasts from Oct. 20 to Dec. 2 and is most visible from the shower's radiant point (the spot in the sky from which they appear to originate) in the direction of the constellation Taurus when it is above the horizon.

At its peak, estimated to occur at around 1:00 p.m. EST (1800 GMT) on Saturday, the Taurids will produce about five meteors per hour. This prediction is made considering perfectly dark skies, however, so actual observing conditions will likely result in fewer meteors being spotted. Unfortunately, the moon will be in a waning gibbous phase tomorrow, meaning the light of the moon might obscure all but the brightest Taurids.

Related: Taurid meteor shower 2022: When, where & how to see it

The Taurids may not be as flashy as other annual meteor showers like as August's Perseid meteor shower or the Geminid meteor shower in December, the latter of which can produce up to 150 meteors per hour, but it is still capable of producing some bright fireballs.

For observers in New York, the Taurids is at its brightest at around midnight when its radiant point is at its highest, according to In the Sky. At this time, the rotation of Earth has turned New York to face incoming meteors as they enter the atmosphere.

This increases the number of meteors passing vertically down through Earth's atmosphere, thus creating short trails. At times when a location isn't facing the incoming meteors, they enter the atmosphere at an oblique angle and create longer-lasting meteors that can get further across the sky.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Looking for a telescope to see the Taurid meteor shower up close? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

The Taurid meteor shower, which occurs each year between September and November, is actually composed of two separate segments, one in the Northern Hemisphere and the other visible over the sky of the Southern Hemisphere. This year, the Southern Taurids began on Sept. 10 and peaked on Oct. 10 and will end on Nov. 20.

Both of these meteor displays originate from the same source, however, a debris cloud left behind by the comet Comet 2P/Encke (Encke).

As the nearly 3-mile-wide (4.8-kilometer) comet approaches the sun on its 3.3-year orbit, Encke sheds dust which lingers in the solar system.

As Earth passes through this cloud of debris, dust from Encke enters the atmosphere at speeds of around 68,000 miles per hour (109,000 kilometers per hour).

This causes them to burn up, creating the Taurid meteor shower. The occasional larger pebble-sized piece of debris will create a bright fireball over Earth.

Skywatchers failing to see any spectacular fireballs during the Taurid meteor shower can catch two meteor showers in December. The Geminids begin on Dec. 4 and peak on Dec. 14, while the Ursids start on Dec. 12 and will peak on Dec. 22.

Editor's Note: If you snap a photo of the Taurid meteor shower and would like to share it with Space.com’s readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.