3 newly discovered worlds risk doom orbiting too close to dying stars

The planets risk being swallowed up by the stars they orbit.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

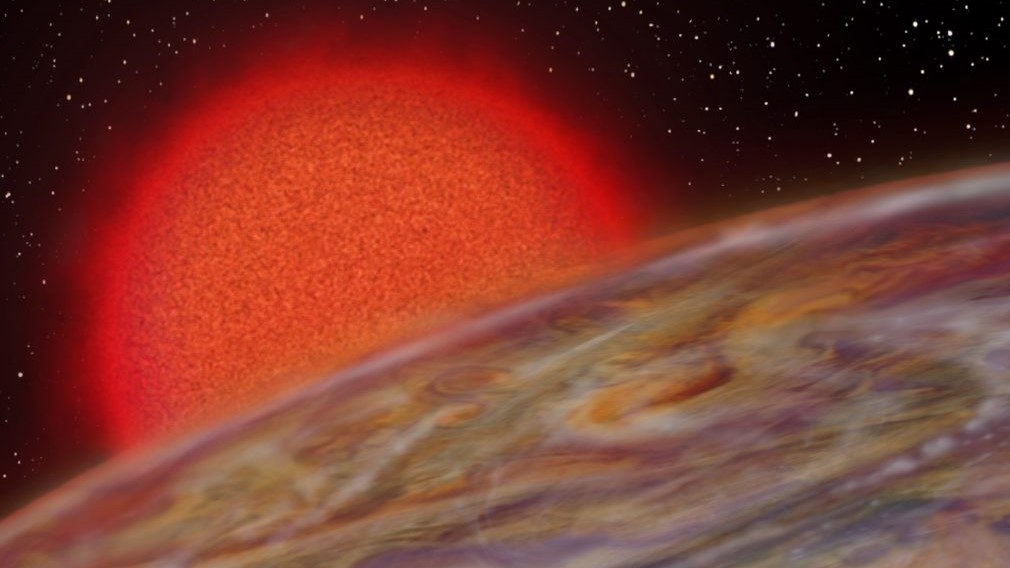

Astronomers have spotted three new exoplanets orbiting dangerously close to their parent stars, on the brink of extinction.

The three exoplanets, named TOI-2337b, TOI-4329b and TOI-2669b, were discovered using NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and the W. M. Keck Observatory's High-Resolution Echelle Spectrometer (HIRES) in Hawaiʻi.

"These planets are in such extreme places that actually less than 10 years ago, no one thought that they actually existed," Samuel Grunblatt, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral fellow at the American Museum of Natural History, said during a news conference held by the American Astronomical Society on Thursday (Jan. 13). The new research was meant to be presented at a conference that the organization canceled due to high rates of COVID-19.

Related: The 10 biggest exoplanet discoveries of 2021

The newfound alien worlds are classified as gas giants, with masses between 0.5 and 1.7 times that of Jupiter. The planets also differ greatly in size and density, suggesting they have varying origins, according to a statement from the W. M. Keck Observatory.

"These discoveries are crucial to understanding a new frontier in exoplanet studies: how planetary systems evolve over time," Grunblatt said in the Keck statement. "These observations offer new windows into planets nearing the end of their lives, before their host stars swallow them up."

As a star evolves and enters the last 10% of its life, it may reel in nearby planets. In turn, altering the planets' orbit around a parent star could destabilize an entire planetary system or cause the planets to collide as they get closer to each other. In addition, as the planets spiral in toward their host stars, they are heated, which can trigger atmospheric changes, such as swelling. This type of interplanetary interaction may explain the varying densities between the newfound alien worlds, according to the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Observations of TOI-2337b, TOI-4329b and TOI-2669b also revealed that the three exoplanets have some of the shortest orbits yet discovered around subgiant or giant dying stars. For example, the orbital period of TOI-2337b suggests the exoplanet will be consumed by its host star in less than 1 million years, which is sooner than any other known planet, according to the study.

"We expect to find tens to hundreds of these evolved transiting planet systems with TESS, providing new details on how planets interact with each other, inflate and migrate around stars, including those like our sun," Nick Saunders, co-author of the study and graduate student at the University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy said in the statement.

Therefore, studying planetary systems like TOI-2337b, TOI-4329b and TOI-2669b may provide a better understanding of our own solar system's evolution, the researchers said.

Further TESS observations are needed to determine the rate at which the newfound exoplanets are spiraling into their host stars. NASA's recently-launched James Webb Space Telescope could also help identify the composition of the planets' atmospheres and, in turn, where the planets formed and how they ended up in such a close-knit orbit around their parent star.

"The rapid changes of the star combined with the short orbital periods of these planets imply these planets should be consumed by their host stars faster than almost any other known planets," Grunblatt said during the news conference. "Continuing the study of these systems could tell us how giant planets move throughout their lives, how that affects their smaller neighbors and then puffs them up during a fiery death dive into their host stars."

Their findings have been accepted for publication in the Astronomical Journal.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.