2 newfound black holes are the closest ever to Earth and like nothing seen before

The two black holes lie just 1,560 and 3,800 light-years from our planet, respectively.

Astronomers have discovered two new black holes that are the closest ones to Earth known, and also represent something that astronomers have never seen before.

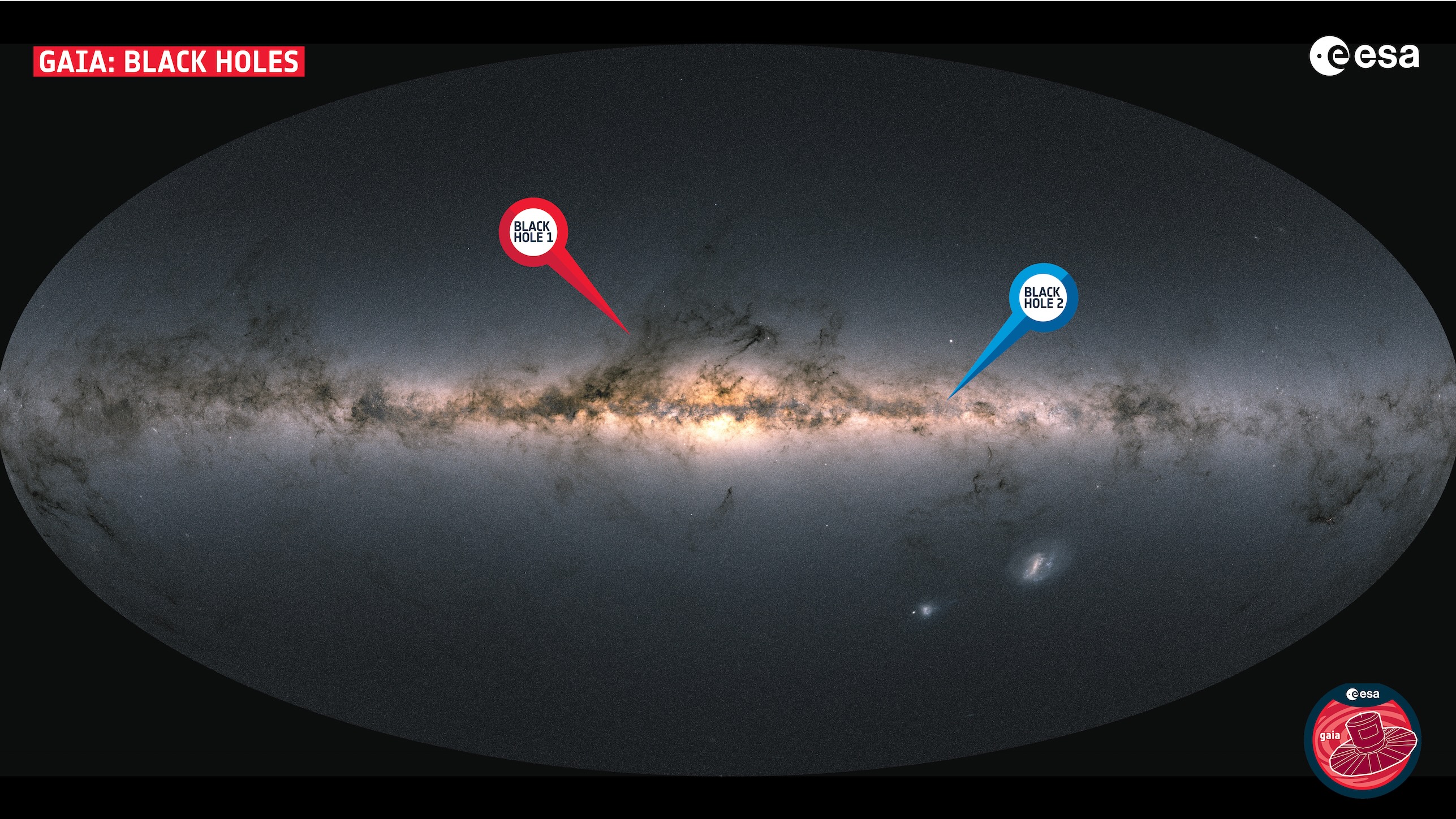

The black holes, designated Gaia BH1 and Gaia BH2, were discovered in data collected by the European Space Agency's (ESA) Gaia spacecraft.

Gaia BH1 is located just 1,560 light-years away from Earth in the direction of the constellation Ophiuchus, while Gaia BH2 lies 3,800 light-years away in the constellation Centaurus. In cosmic terms, both black holes are therefore situated in Earth's backyard.

Related: Black holes of the universe (images)

It isn't just the proximity of these black holes to Earth that makes them extraordinary, however. They are orbited by stars at much greater distances than has previously been observed in other black hole-companion star pairings.

"What sets this new group of black holes apart from the ones we already knew about is their wide separation from their companion stars," discovery team leader Kareem El-Badry, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Massachusetts and the Max-Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, said in a statement.

"Normal" black hole-companion star systems are called X-ray binaries and are usually bright in high-energy X-ray and radio emissions. This makes them easier to find than black holes that aren't swallowing matter and thus aren't emitting powerful bursts of energy. Gaia BH1 and Gaia BH2 are completely dark and were detected via the gravitational effect they have on their companion stars.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"These black holes likely have a completely different formation history than X-ray binaries," El-Badry explained. "We suspected that there could exist black holes in wider systems, but we were not sure how they would have formed. Their discovery means that we must adapt our theories about the evolution of binary star systems, as it is not clear yet how these systems form."

Gaia is ideal for spotting 'invisible' black holes

Gaia is equipped to make such discoveries because it can accurately measure the position and motion of billions of stars against the background sky. Tracking this stellar movement so precisely hints at the gravitational influences exerted on these stars from other stars, orbiting planets and black holes, researchers said.

"The accuracy of Gaia's data was essential for this discovery," said ESA Gaia project scientist Timo Prusti. "The black holes were found by spotting the tiny wobble of its companion star while orbiting around it. No other instrument is capable of such measurements."

The Gaia observations were backed up by measurements of each companion star's motion made by other observatories. For example, follow-up investigations of Gaia BH2 with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the South African MeerKAT radio telescope on the ground revealed no detectable light coming from this black hole.

"Even though we detected nothing, this information is incredibly valuable because it tells us a lot about the environment around a black hole," said discovery team member Yvette Cendes, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

"There are a lot of particles coming off the companion star in the form of stellar wind," Cendes said. "But because we didn't see any radio light, that tells us the black hole isn't a great eater and not many particles are crossing its event horizon. We don't know why that is, but we want to find out!"

The team will now attempt to discover more widely separated black hole binary systems in the next data dump from Gaia, set to release in 2025. This new data will be based on 66 months of observations from the spacecraft and feature more detailed information on the movement of stars.

"This is very exciting, because it now implies that these black holes in wide orbits are actually common in space — more common than binaries where the black hole and star are closer. But the trouble is detecting them," Cendes concluded. "The good news is that Gaia is still taking data, and its next data release will contain many more of these stars with mystery black hole companions in it."

The discovery of these two black holes is detailed in a paper published late last month in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.