For Artemis moon missions, science will reign supreme

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

On April 15, planetary scientist and NASA astronaut Jessica Watkins will launch to the International Space Station and, as such, will likely be in space when the agency's Artemis 1 mission launches to the moon.

The scheduling, which will be Watkins' first spaceflight and will make her the first Black woman to fly an extended mission in space, is a coincidence. But it also shows how NASA is approaching human spaceflights as the agency approaches working toward a crewed return to the moon with its Artemis program.

Watkins, a Ph.D.-holding geoscientist, is part of the Artemis Team of NASA astronauts the agency has pegged for future moon landings. And agency personnel have emphasized that science will be front and center as the Artemis program unfolds.

"It is a pleasure to know that we've got a good scientist going up there," NASA chief exploration scientist Jacob Bleacher said during an "Artemis town hall" that was livestreamed at this year's Lunar and Planetary Science Conference on Thursday (March 10). "The entire astronaut group at this point, are strong advocates for utilization for science," Bleacher added.

Related: NASA's Artemis 1 moon mission explained in photos

Bleacher said such a commitment is due to NASA's astronauts seeing the scientific potential in landing people on the moon for the first time since 1972.

"They very well know that they are kind of the tip of the spear, which we are all a part of, as we try to conduct this research and understand our Earth, our moon, the planets, the solar system [and] the universe within which we reside," Bleacher added.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These comments came just one week before NASA's uncrewed Artemis 1 mission headed out to the launch pad during a rollout on March 17. That mission, which NASA aims to launch no earlier than May, will send the agency's Space Launch System (SLS) megarocket and Orion capsule (uncrewed) on a trip out past the moon and back.

Should Artemis 1 go to plan, NASA hopes to launch Artemis 2 in 2024 for a round-the-moon crewed trip, followed by Artemis 3 touching down on the lunar surface no earlier than 2025. (A 2026 lunar landing is probably more likely recent issues identified by NASA's inspector general.)

Bleacher emphasized that whenever the moonbound astronauts arrive on the moon's surface, they will have a much different focus than the agency's Apollo astronauts which last touched down on the moon in 1972.

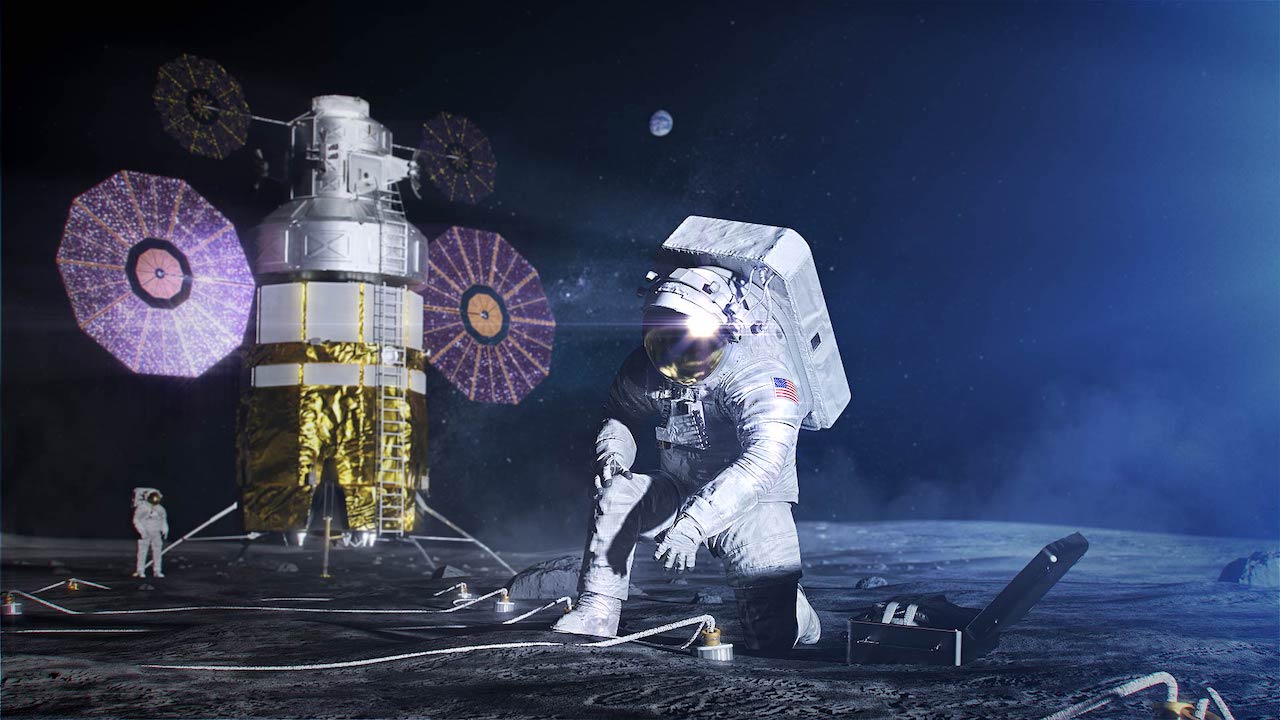

"This is not simply returning to the moon. This is boldly exploring a new area that we've never been to, and it will require new and creative approaches," Bleacher said. For example, the astronauts will land near the lunar south pole and, eventually, will likely be tasked with trying to "live off the land" and using local resources such as ice to support operations and human living.

Crew training for the Artemis astronauts, he added, includes an emphasis on the "science perspective" of these missions from the beginning. This will ensure that astronauts with less scientific experience will have the time to accumulate that experience.

"We would like that bring them up to speed as much as we can, and so that includes not just training them at the last minute to pick up the right rocks on the moon. It's not — I think you all know — that's not how science works. You can't just learn it all at the last second," he said.

Bleacher emphasized that this training is ongoing and that astronauts train consistently for long periods of time, rather than being tasked with learning something and then being asked to relearn it a few years later. This approach, he said, is to avoid trying "to cram a bunch of stuff in at the end."

Analog, or simulated, training activities, for example, are ongoing in various locations around the United States as well as in icy locations such as Iceland, so astronauts learn how to core and collect samples in icy terrains.

"One of the reasons that we are going to the south polar region with Artemis is because we believe there to be volatiles there that we can gain access to," Bleacher said; water is an example of a volatile substance.

"We we want to learn how to do that correctly," Bleacher said of the ice collection on the moon. "That's different than what we did during Apollo. We have learned a lot from Apollo ... but again, the south polar region will be a unique environment that we have not operated in, in the past."

Yet NASA emphasizes that the lessons from the Apollo moon missions are still helpful in forming the Artemis program, as they can build upon the lived experience of the thousands of individuals who made the 1960s and 1970s moon landings possible, as well as the diagrams, writing and technical information left behind.

Other programs will feed into the planning of Artemis as well, Sarah Noble, a program scientist in the planetary science division at NASA headquarters, added during the discussion. This includes the cancelled George W. Bush-era Constellation program that aimed to send humans both to the moon and Mars.

"We are not starting from scratch, right?" Noble said at the same conference. "We're building on Apollo, we're building on even Constellation and all of the planning that we have been doing over the last 50 years, repeatedly, to get to this point. And so none of that has been wasted."

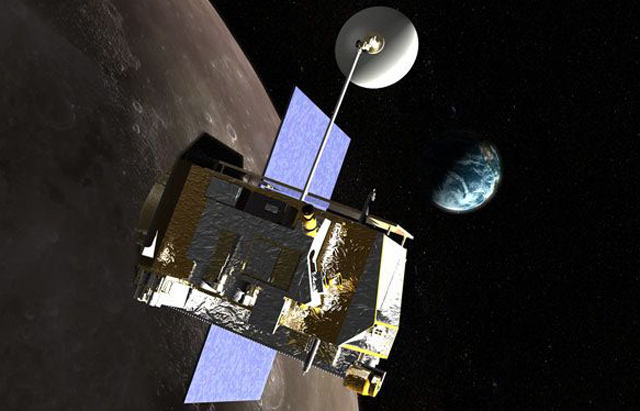

Noble added that the lunar science community has changed over the years as well, benefiting from a wealth of new information delivered from lunar orbit (such as through NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.) With the work of LRO and other spacecraft, she noted, science planning is "embedded in every layer of Artemis planning from the beginning."

Science, she added, "is at the table. We're sitting in those meetings, making sure that somebody is speaking up for science. As all of these planning is happening, as all these systems are being developed, there's somebody in the room that can stand up and say, 'Hey, that's not going to work for us. Let's find another way.'"

"It's not easy. This is not Apollo. This is not ISS. This is not shuttle. This is Artemis. It is different," he added. "It is brand new. It's complicated. And we're doing things; some of these things we're doing for the first time. We've learned a lot from all of that work ... we are certainly standing on the shoulders of giants. But this is new, and it's exciting. And I hope that you all understand how exciting this is."

He asked that NASA groups working on Artemis think of collaboration first, and that they be understanding when the inevitable snags occur in development.

"We're not competing here," he said. "All of us are supporting all of us, okay? Be kind to each other. Be kind to the people around you. Even if you are on competing teams, be kind to each other. This is not a 'one winner only' kind of thing. We have to work together for this to be successful over the long run."

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.