Jupiter shines near the moon with the Seven Sisters of the Pleiades on July 14. Here's how to see it.

Stay up late to see a trio of fascinating sights in the early morning sky overnight.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

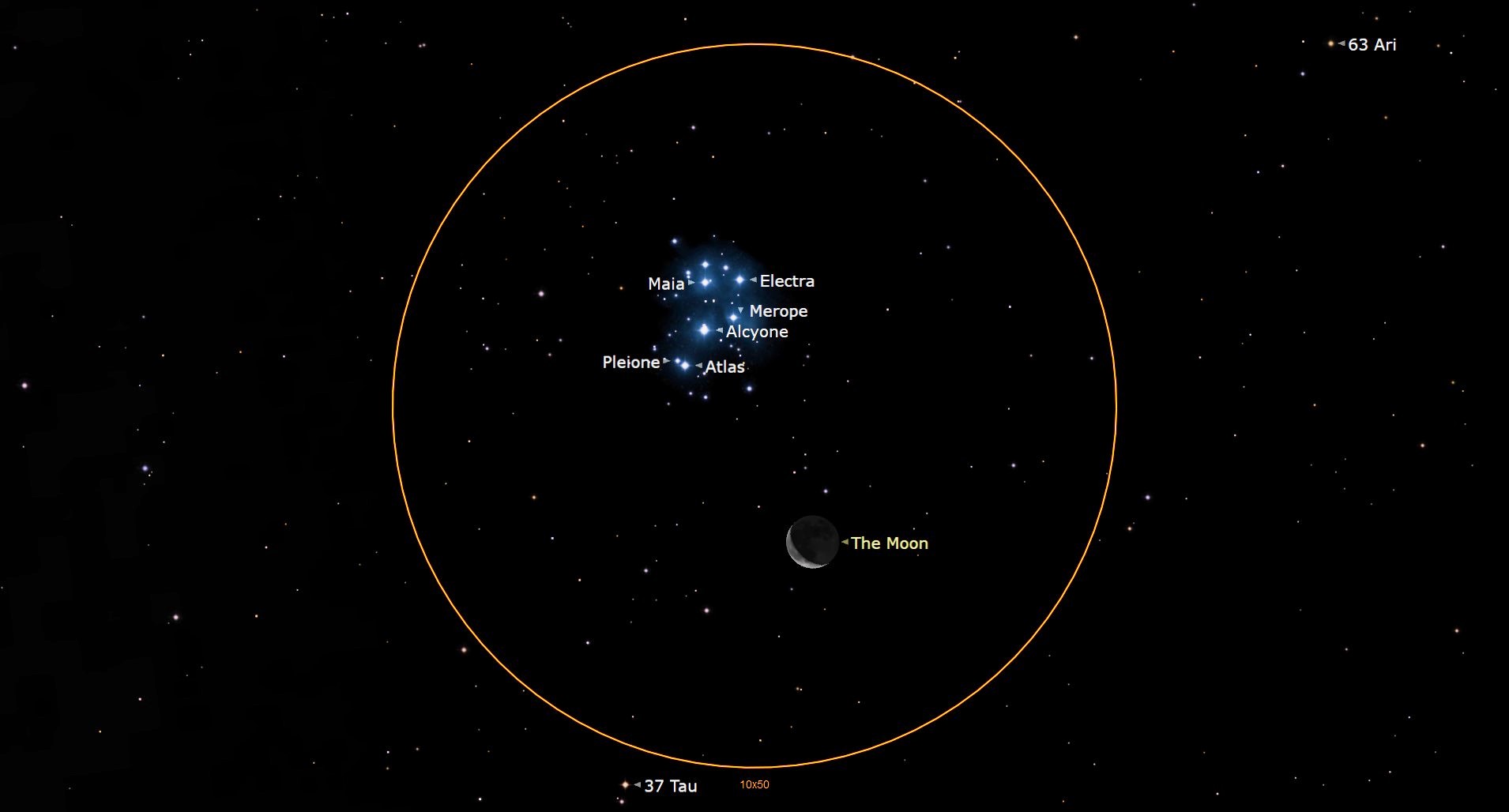

The moon has a date with the Seven Sisters star cluster, also known as the Pleiades, in the early morning hours of Friday, July 14.

Skywatchers on Earth won't be the only ones looking over this celestial encounter between the moon and the Pleiades; both Jupiter and the brightest star of Taurus, Aldebaran, will play chaperone and cast their gaze over the proceedings.

As seen from New York City, Jupiter and the Pleiades will rise around 1:30 a.m. ET (0530 GMT) on Friday, July 14, while the moon will rise just after 2:30 a.m. EDT (0553 GMT) and will set at 6:30 p.m. EDT (2230 GMT). The moon will be in its waning crescent phase during the encounter with Pleiades as it darkens, approaching the next new moon on July 17 and the start of the new 29.5-day lunar cycle.

Related: Night sky, July 2023: What you can see tonight [maps]

Read more: What is the moon phase today? Lunar phases 2023

Looking for a telescope to see Jupiter, the moon or the stars of the Pleiades? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

During the encounter, which occurs in the Taurus constellation over the horizon to the east, the moon will be located around one hand's width below and to the left the Seven Sisters. Jupiter will be above and to the right. (As a bonus, Uranus will be located roughly halfway between the Pleiades and Jupiter, although it is certainly not visible to the unaided eye and can be difficult to observe even with optical aid.)

The arrangement will likely be too wide to fit in the view of binoculars, but all of these objects will make for an impressive celestial scene to the unaided eye.

The Pleiades is named after the even daughters of the Titan god Atlas and the ocean nymph Pleione in Greek mythology. The family connection is apt because the Pleiades is an open star cluster, a system in which all the stars are believed to have been born from the same cloud of gas and dust. This makes the Pleiades a true family of stars which still move together through space.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Also located in the constellation of Taurus and close to the meeting of the moon and the Pleiades is one of the brightest stars over Earth, Aldebaran or Alpha Tauri, the "Eye of the Bull." A red giant star located around 65 light years from Earth, Aldebaran, is 44 times as wide as the sun.

The association of this red giant with the Pleiades is reflected in its name, "Aldebaran," deriving from the Arabic "al Dabarān" ("الدبران"), which means "the follower." This likely refers to the fact that in the Northern Horizon, Aldebaran follows the Pleiades over the horizon.

If you are hoping to catch a closer look at the moon and the Pleiades in the night sky, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

And if you want to try your hand at photographing the moon and the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to photograph the moon, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor's Note: If you snap an image of the moon and the Pleiades and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.