Astronomers spot remains of long-lost galaxy eaten by the Milky Way

The demolished galaxy crashed into our own 8 billion to 10 billion years ago.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The Milky Way galaxy feasted on more galaxies in its early days than astronomers thought.

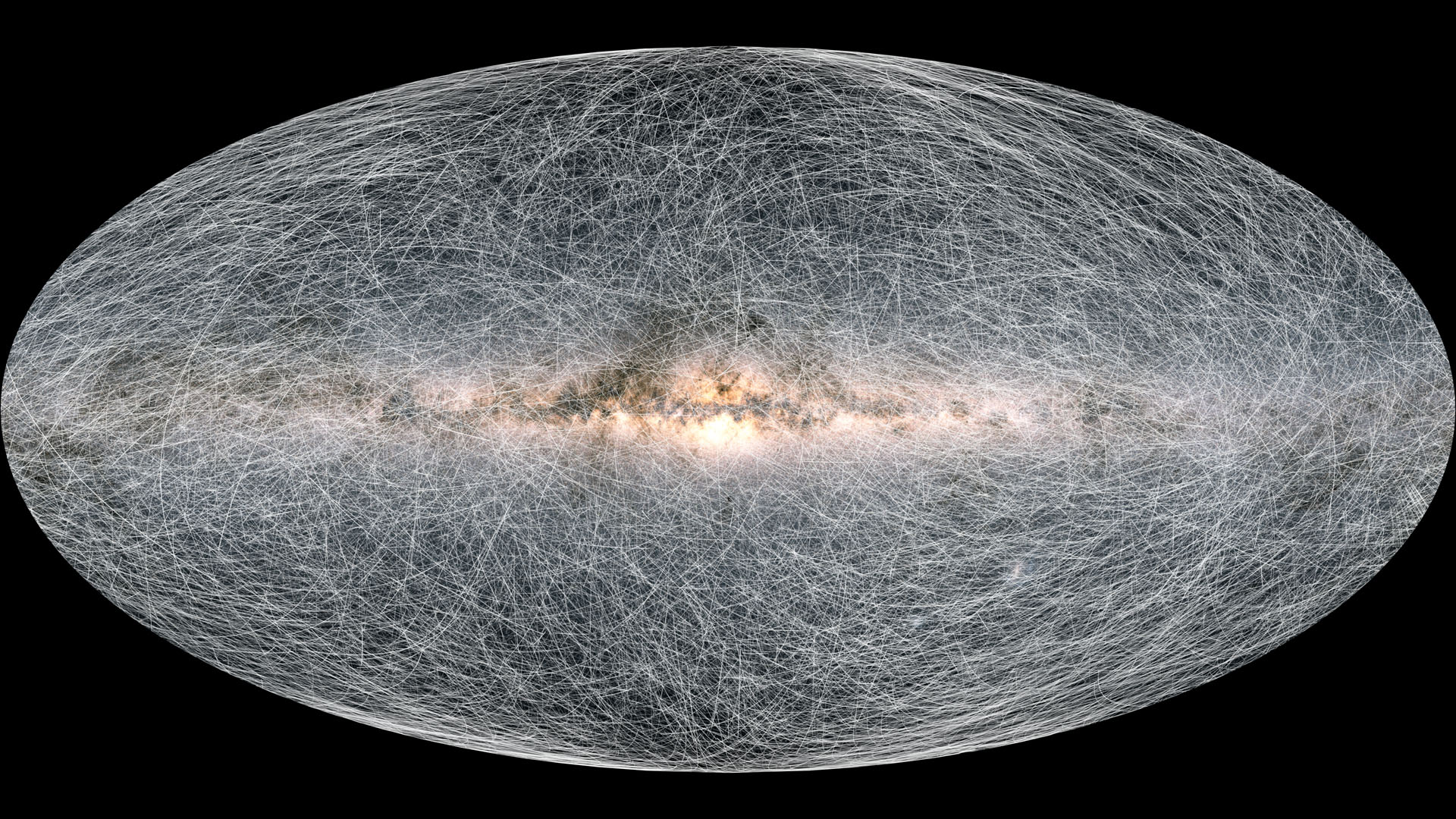

The Gaia spacecraft uncovered the remains of an ancient cosmic collision in our Milky Way, revealing a previously unknown galaxy, now nicknamed "Pontus," absorbed by the Milky Way long before our galaxy looked the way it does now.

Pontus was a galaxy that strayed too close to the Milky Way and "fell in" to our galaxy's gravity about 8 billion to 10 billion years ago, the European Space Agency, which operates Gaia, said in a statement Thursday (Feb. 17).

Related: See a virtual Milky Way map from Europe's Gaia spacecraft

Events like this merger are important to learning about the Milky Way, ESA added, as it shows "the 'family tree' of smaller galaxies that has helped make the Milky Way what it is today."

Gaia launched into space nearly a decade ago, in 2013, on an ambitious mission to chart the sky in three dimensions more precisely than ever. Movements of stars and other objects nearby us will in turn reveal insights about the Milky Way's composition, formation and evolution, mission managers say on the Gaia website.

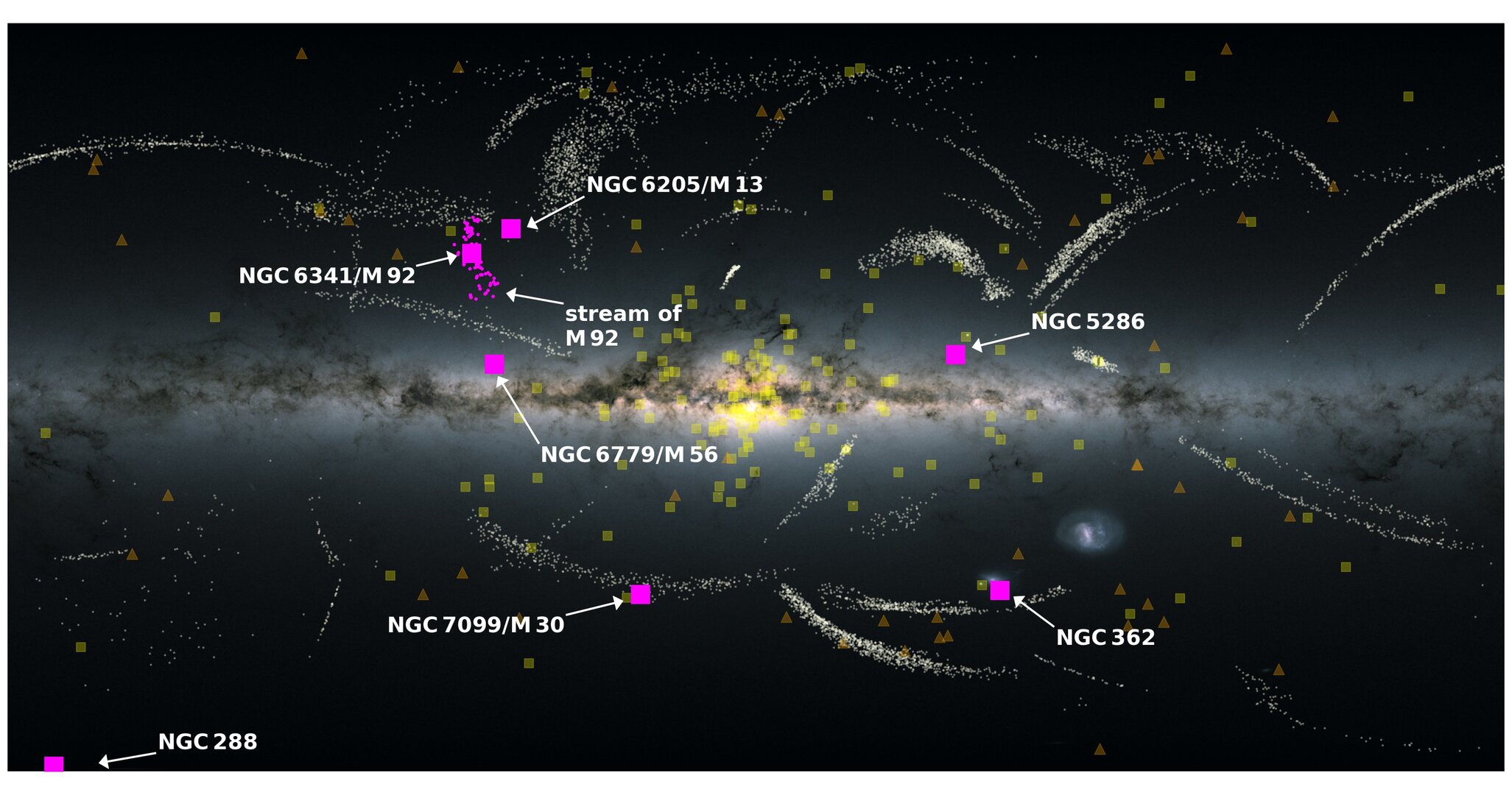

This latest work on galactic mergers arose from a study of the Milky Way's halo, which is a zone filled with globular clusters of older stars, stars that have low metallicity, and other interesting objects. "Foreign galaxies" in the halo may show up in this region in different ways, depending on the speed of the collision, ESA stated in the press release about the study.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"When a foreign galaxy falls into our own, great gravitational forces known as tidal forces pull it apart," ESA stated. "If this process goes slowly, the stars from the merging galaxy will form a vast stellar stream that can be easily distinguished in the halo. If the process goes quickly, the merging galaxy's stars will be more scattered throughout the halo and no clear signature will be visible."

Stars are not the only way by which we may detect a merging galaxy, however. If the intruder contains globular stars or small satellite galaxies, these may also show up in the halo. The new study focused on looking for this data.

Scientists named the incident after Greek mythology, which identifies Pontus as one of the first children of Gaia, the goddess of the Earth.

Besides finding the Pontus event, the team identified five other distinct merging groups (already known to science) and a possible sixth in the data. The already known five events are called Sagittarius, Cetus, Gaia-Sausage/Enceladus, LMS-1/Wukong, and Arjuna/Sequoia/I’itoi.

ESA noted that Pontus and most of these other events happened around the same time period, 8 billion to 10 billion years ago, but Sagittarius is more recent at 5 billion to 6 billion years ago. "As a result, the Milky Way has not yet been able to completely disrupt it," the agency added of the Sagittarius event.

A study based on the research was published Thursday (Feb. 17) in The Astrophysical Journal, led by Khyati Malhan, an astrophysicist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. The work was based upon an early release of Gaia's third large set of data, set to drop on June 13.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.