Our sun is a weirdly 'quiet' star — and that's lucky for all of us

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Thank your lucky stars that the sun is pretty weird, as scientists have learned by comparing its activity with that of similar stars.

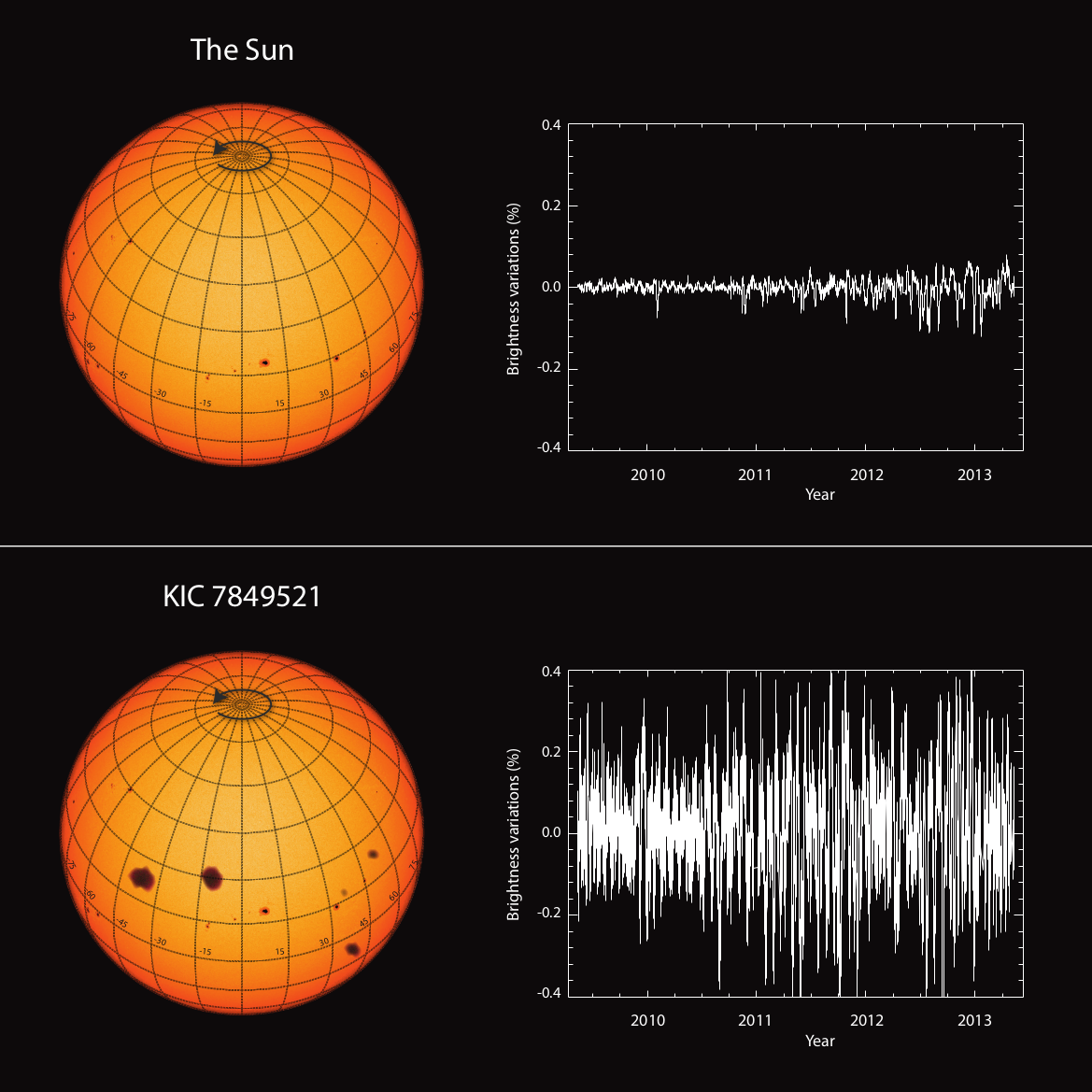

In new research, astronomers compared the brightness of our sun over time with data gathered on other stars by NASA's Kepler Space Telescope and by the European Space Agency's Gaia star-mapping mission. The result is a census of stars about the same size of our sun. But compared to these stars, our sun's brightness varies significantly less, suggesting that it is calmer than other stars of about the same size.

"We were very surprised that most of the sun-like stars are so much more active than the sun," Alexander Shapiro, a physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany and a co-author on the new research, said in a statement.

Related: World's largest solar telescope produces never-before-seen images

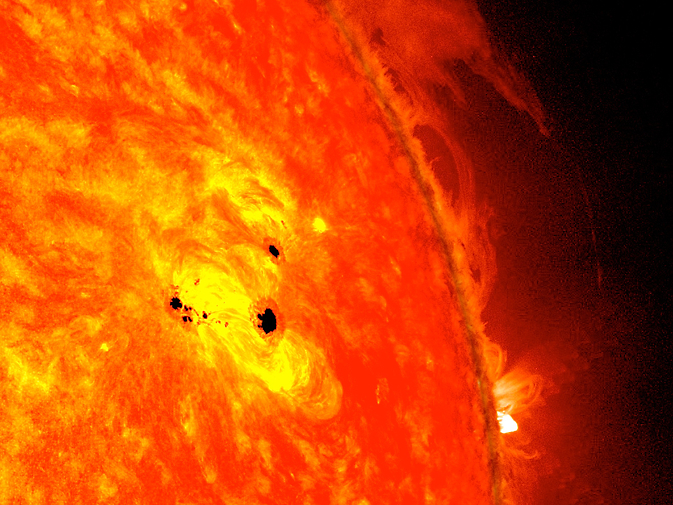

Scientists are well acquainted with the sun's current behavior, of course, and have astronomical observations of dark spots on its surface going back about 400 years. Those sunspots are crucial information about the activity of the sun: They are driven by the sun's magnetic field and massive outbursts of radiation and matter stem from them.

To understand what the sun was doing before those records begin, scientists can interpret a host of data types, like levels of specific elements in tree rings and ancient ice. With those aids, researchers have constructed estimates of the sun's activity going back about 9,000 years. The modern sun matches that record pretty well, the researchers said — but that doesn't mean those 9,000 years are representative of the sun's 4.6 billion years of existence.

"Compared to the entire lifespan of the sun, 9,000 years is like the blink of an eye," Timo Reinhold, lead author of the new study and an astrophysicist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, said in the same statement. "It is conceivable that the sun has been going through a quiet phase for thousands of years and that we therefore have a distorted picture of our star."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Reinhold and his colleagues wanted to compare the sun's known activity with what other similar stars are doing. Scientists can't track sunspots on distant stars directly, but these dark patches on a blazing ball of plasma do affect the brightness of the star. Because all stars rotate, sunspots are carried around the star, causing its brightness to fluctuate — and scientists know very well how to track variations in brightness of a star over time.

That type of data forms the backbone of one of astronomers' main techniques for discovering exoplanets, and NASA's Kepler Space Telescope was tailored to measure tiny changes in the brightness of an individual star over time. So the researchers behind the new study went digging in that data.

The astronomers narrowed down a collection of tens of thousands of stars by focusing on those with about the same surface temperature, surface gravity, age and metallicity as our sun. Then, they split these stars into two batches: one containing 369 stars that rotate every 20 to 30 days and one with 2,529 stars that scientists haven't been able to calculate a rotation period for. (The sun rotates every 24.5 days, but that spin likely wouldn't be detectable to alien astrophysicists using the same techniques humans have, so both of these groups of stars are important.)

The researchers then analyzed both these groups of stars to understand their activity levels and how they compare with the sun. Stars with known rotation rates were on average much more active than our sun has been over the past 9,000 years — about five times more active. The stars without tracked rotations were less active, much more in line with the sun.

That split poses a puzzle for scientists: Either there's something fundamentally different between clockable stars and unclockable ones, or something has been making the sun much quieter than stars like it for at least the past 9,000 years.

Right now, there's no way to tell which is correct. But it's definitely not a bad thing that our sun is relatively calm: Its outbursts can endanger our technology in orbit and on Earth's surface, and if it were very, very active, the sun's temper could threaten life itself. Fortunately, there's no sign the sun will get rowdy soon, and scientists have predicted that the upcoming 11-year solar cycle should be reasonably tame.

The research is described in a paper published May 1 in the journal Science.

- 10 brilliant discoveries NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory made in its first decade in space

- Our sun will never look the same again thanks to two solar probes and one giant telescope

- Scientists' favorite sun photos by Solar Dynamics Observatory (gallery)

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.