A lander on Jupiter's icy moon Europa may have to dig at least 1 foot down to find signs of life

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Robots may have to dig relatively deep on Jupiter's icy moon Europa to have a shot of finding signs of life, a new study suggests.

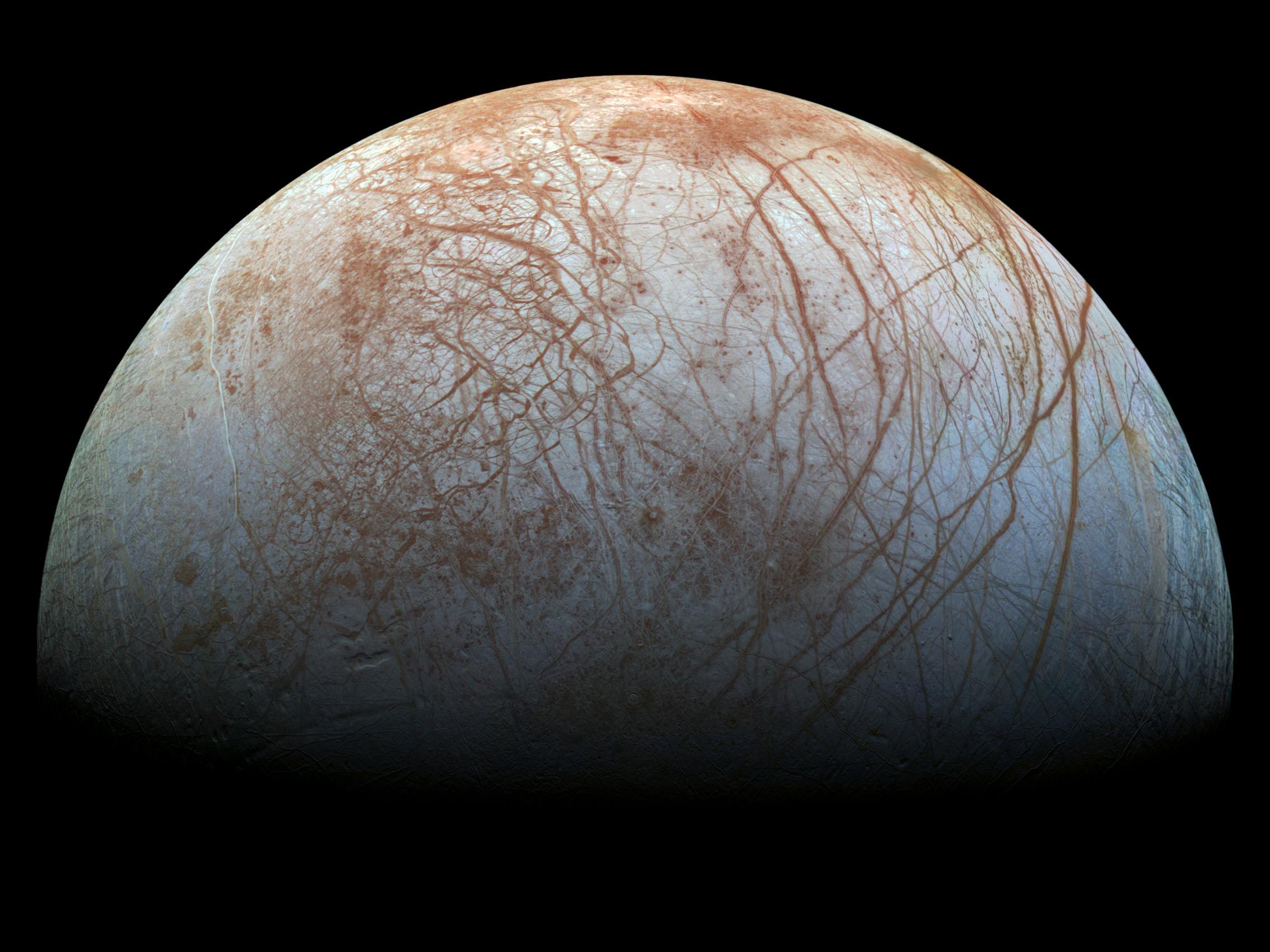

Scientists think Europa harbors a huge ocean of liquid water beneath its icy shell. This ocean appears to be in contact with the 1,940-mile-wide (3,100 kilometers) moon's rocky core, making possible a range of complex chemical reactions. As a result, Europa is generally regarded as one of the solar system's best bets to harbor alien life.

If life has ever existed on Europa, some signs of it may bubble out of that buried ocean onto the surface, where robots could potentially spot it. Well, not right on the surface; Europa gets hammered hard by charged particles, which are trapped and accelerated by Jupiter's powerful magnetic field.

Article continues belowPhotos: Europa, mysterious icy moon of Jupiter

Previous work has suggested that just 8 inches (20 centimeters) of ice could likely shield any biomolecules that might exist on Europa from that punishing radiation environment, even in the hardest-hit regions of the moon.

The new study, which was published Monday (July 12) in the journal Nature Astronomy, is a bit more pessimistic. In it, researchers modeled how Europa's surface is distubed by small but frequent impacts — a real issue for a world without a substantial atmosphere to burn up incoming hunks of rock and ice.

They found that such "impact gardening" likely churns the top 12 inches (30 cm) or so of Europan ice significantly, bringing previously buried bits up to the surface, where radiation can zap any interesting molecules into unrecognizable goo.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If we hope to find pristine, chemical biosignatures, we will have to look below the zone where impacts have been gardening," study lead author Emily Costello, a planetary research scientist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, said in a statement. "Chemical biosignatures in areas shallower than that zone may have been exposed to destructive radiation."

The new work is likely of interest to NASA, which plans to launch a Europa spacecraft in 2024. The mission, called Europa Clipper, will orbit Jupiter but study the moon and its buried ocean over dozens of close flybys.

Clipper's many duties also include scouting out potential touchdown sites for a life-hunting lander — a mission that Congress has directed the agency to mount but which remains a concept for now.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.