20 years of otherworldly thought experiments: A Q&A with artist Jonathon Keats

The master of the absurd but profound thought experiment is getting some of his artistic due.

For the past two decades, Jonathon Keats has been asking us to recalibrate our assumptions about the universe and our place in it, through a series of projects that bury multiple layers of meaning beneath a veneer of playfulness and seeming frivolity.

Many of Keats' efforts have a space theme, or at least draw inspiration from humanity's scrabbling attempts to explore and understand the final frontier. In 2006's "Speculations," for example, he sold the development rights to the extra dimensions predicted by string theory. Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist Saul Perlmutter served as a consultant on the project.

In 2011, Keats pushed for a Copernican revolution in the arts, urging painters, composers and writers to strive for the mediocrity that defines our universe rather than strain to create jarringly atypical masterpieces.

And six years later, Keats and space archaeologist Alice Gorman developed a potential solution to the Fermi Paradox — a "cosmic welcome mat" designed to let passing aliens know that we'd happily receive them here on Earth. (Perhaps they've been waiting for just such an invitation.)

Alien thinking: The conceptual space art of Jonathon Keats (gallery)

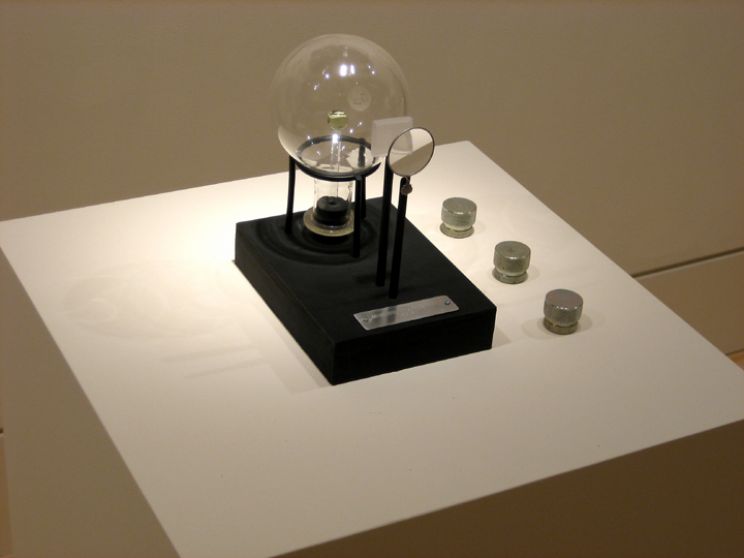

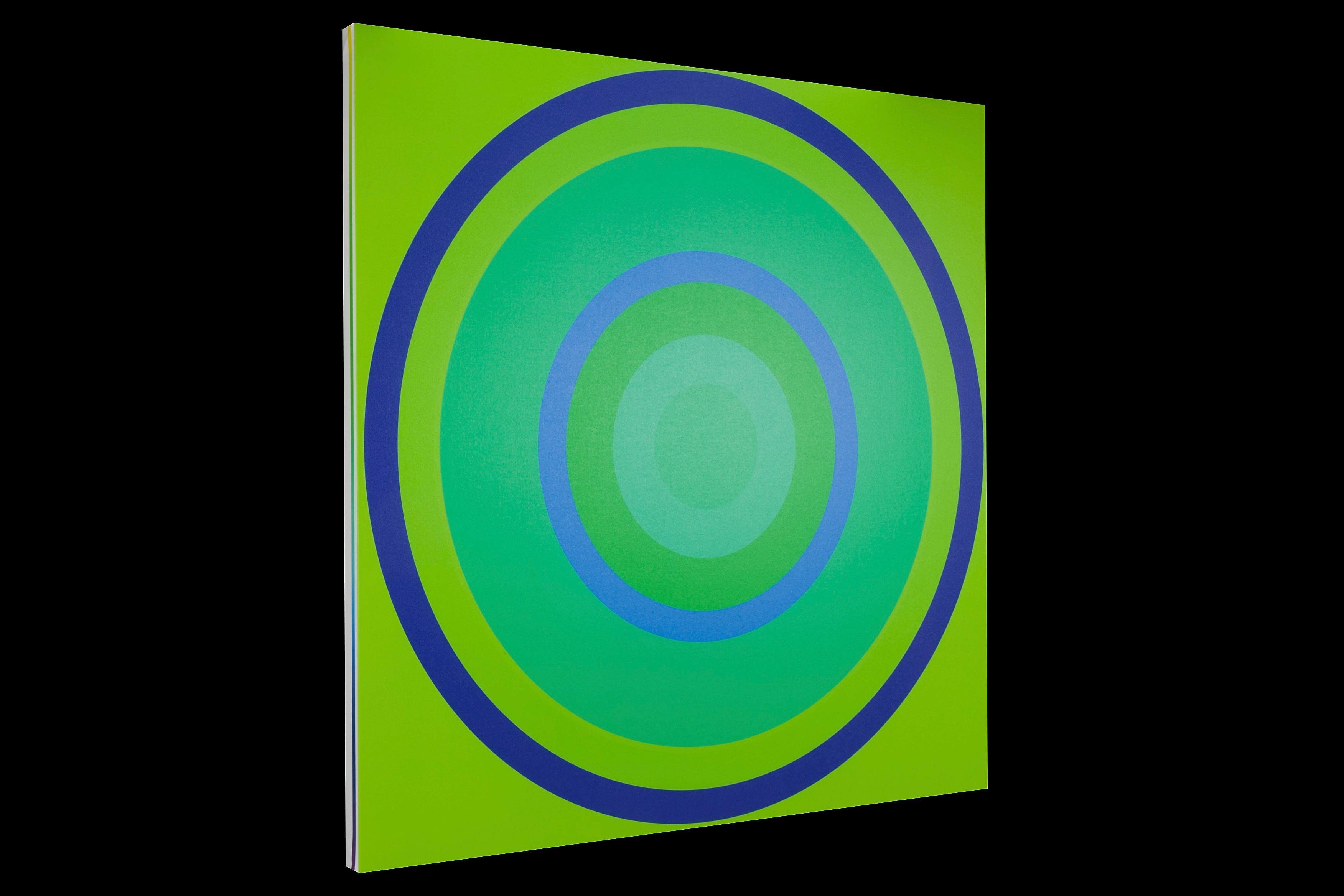

These installations and many more have been shown in galleries around the world — and you'll soon be able to keep a diverse sampling of them on your coffee table. "Thought Experiments: The Art of Jonathon Keats" (2021, Hirmer), a monograph celebrating and examining his work, comes out next Thursday (April 15) and is available for pre-order now on Amazon.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Thought Experiments," which will be published by the German house Hirmer, features deep dives into 20 of Keats' projects, with accompanying essays by folks such as sci-fi writer Bruce Sterling, Science Gallery founder Michael Jon Gorman, and the monograph's two editors, art historian Alla Efimova and Anchorage Museum director Julie Decker.

Space.com caught up with Keats recently to discuss why he keeps dipping into the infinite space well, the importance of absurdity in art and how it feels to be the focus of a 350-page book. The following interview has been edited for length. (It's much shorter and less detailed than the one in the monograph.)

Thought Experiments: The Art of Jonathon Keats. $45 at Amazon.

Celebrate 20 years of conceptual space artist Jonathon Keats in this new Hirmer book by editors July Decker and Alla Efimova. It is available April 15.

Space.com: I've written about a lot of your projects, because you touch on space so much and in such interesting ways. Why do you think that space is such a recurring theme with you? What is it about space science and exploration that fits so well with what you're doing?

Jonathon Keats: At the most basic level, the most banal level, I am interested in everything. And I am especially interested in what others are interested in, and interested in activating deeper and alternative ways of thinking about them. So, if we were not in the space age, I might not touch on space as much as I do.

In the same way, I find myself engaging in questions related to economics and politics a lot right now, and also to an ever greater extent in terms of ecology. I'm looking at space and into space because we really need to be thinking deeply about what we are trying to do when we look out there, and potentially when we go to other planets, and even, possibly, colonize them.

But the deeper level, or a level that is perhaps not quite as banal as that, is the philosophical level. And here I am in no way being original, because there's a long tradition of philosophers taking space as a subject in order to be able to think expansively, or to look upon our world from an outside perspective. That's the move that I am making when I undertake a thought experiment in any case, and space is manifestly alternate in the sense that it is not here, and by virtue of the fact that it is there, it becomes a vantage for looking at here.

And, moreover, it is the unknown, in its most vast and most extensive form. The fact that we cannot, in physical terms, access the multiverse or get beyond the horizon established by the Big Bang means that there is inherently an unknown, and even where there is the possibility physically to make observations, access is incomplete.

The universe: Big Bang to now in 10 easy steps

So space invites speculation, and it invites speculation in a way that is complicated by the fact that it is neither entirely fictional nor entirely factual. Which is not to say that astronomers are not rigorous; many of them are. But, nevertheless, looking out into space and taking space as a place in which to place work and to set ideas sets aside inherently a lot of assumptions and militates against any misuse of experiences that might distort our thinking, because we know we haven't been there. And that's a great starting point, I think, for being able to think about things without assuming.

And finally, it's really a matter of all of the many different possibilities that there are for considering some of the greatest issues of our time by way of extrapolation. I'm thinking specifically of all the ways in which qualities such as tolerance and xenophobia, potentially, are addressed when we consider the more extreme case of being from elsewhere in the universe in order to put in perspective the alien nature, or the alien identity, we place on beings who are down on the border.

There are so many opportunities. And I think that every time that I start to develop a new work, I find new resonances.

Space.com: Maybe I'm wrong about this, but it also strikes me that there's something fundamentally absurd about space and our attempts to understand it, because in some ways those attempts are futile. Our brains aren't well equipped to understand things on the quantum scale, or on the scale of the very large. In the Q&A in the new book, you mention that absurdity is often a key part of your thought experiments — that it helps people get into the right frame of mind to access them. So do you think there's a sort of marriage between the absurdity of space and the absurdity that you aim for in much of your work?

Keats: I find the absurd to be productive, because the absurd is disorienting and therefore calls for a reorientation. The absurd has that quality in common with elsewhere, where elsewhere is another planet or another galaxy.

So I think that the absurd is perhaps the condition of outer space in microcosm. There's also, as you point out, the futility, which is, I think, a quality that's related to absurdity — the absurdity of asking some of the questions that we feel impelled to ask as a result of the answers that we have to the questions that we asked previously that perhaps were more answerable, and the ultimate delocalization of our focus, the ultimate opening up of our purview.

In other words, I don't think that you would find many Cro-Magnons having conversations about the multiverse. I could be wrong; I'm not Cro-Magnon, and I wasn't there. But certainly, I would not be surprised to find Cro-Magnons having profound discussions in whatever form that might be — and it may not involve any given language as we currently define language — about physics, the physics that relates to what was in their midst.

And so what we find in the sciences, I think, are theories that build on observations, and those theories then suggest new areas of observation, and this iterative process leads us to a greater and greater purview. And, in some way, the story of how we came to ask whether there's a multiverse is a story that begins with Cro-Magnons, or with whatever other hominid you choose, trying to figure out how best to attach stone to wood, or more generally, how to get the next meal.

That is really interesting to me, because it's a way in which the practical leads us naturally, seemingly — or inevitably, maybe, given the way that our minds work — to the futile. And there's something that is really absurd in the question of whether there is a multiverse, because it is a question that is unanswerable and yet there's something inevitable about it. And the fact that it's inevitable makes it even more absurd and brings that quality of absurdity home to all of the questions that were proximate, all the questions that got us there, so that we, I think, as a result of this, end up less certain about what was absolute, or what we thought we knew in our own midst.

So the de-centering effect, or the disorienting effect, comes right back around and leads us to question what we thought we knew, and to enter into an uncertainty that I think is essential from the standpoint of sustaining an openness, a curiosity and a capacity to the sort of tolerance and mutual efforts toward some set of common interests that can sustain us as a society.

Space.com: Of all your space-related projects, are there any that stand out in particular as your favorites?

Keats: I find that I keep coming back to some of the questions that initially arose in the "First Copernican Art Exposition," which I don't think is included in the book, then was, in fuller form, or even more developed form, the basis for "Intergalactic Omniphonics."

I think that in many ways, that project is one that continually gives more, the more that I delve into those questions and try to develop those ideas. And I think that is because the project allows for — invites, insists upon — a way in which to frame our lives here on Planet Earth today in terms that are nearly infinite, spatially and temporally. And therefore the project has urgency, especially in terms of the political issues that are brought to bear around questions of tolerance, but also that the project [derives] from that very tangible and immediate relevance and the interactions that come about because of that relevance, such that the biggest questions of all are generated through those interactions. And by that I mean, questions about whether we are alone — but more than that, what might constitute life and intelligence aside from the example that we have here on Earth.

That is to say, that we can start to speculate in a rigorous way about sensory systems, about cognition, about all of the many questions that are latent and, I think, go unexplored about ourselves. They are activated through speculation about others and through the process of trying to bring us all together and to find commonality to discover universality. It is, I think, a very powerful mechanism by which to recognize and appreciate difference, and to therefore better understand and appreciate who and what we are.

Related: 13 ways to hunt intelligent aliens

Space.com: Another recurring topic in your work is environmental degradation, especially the damage we're inflicting via human-caused climate change. Do you feel a sense of responsibility to try to get people to think about and mitigate such issues, to try to make the world a better place?

Keats: I absolutely feel a sense of responsibility, and I want to do what I consider to be important. Even if I'm not necessarily contributing anything of any value, I can at least try to do some good. And I can use the methodologies that I've developed to the best of my ability toward that end.

So there is the external factor, that climate and climate change are being discussed and debated right now. And because I tend to see any given conversation that is becoming a major conversation or is predominant as being a conversation that I want to participate in; and also because I see climate catastrophe as being a real possibility; and also because I see our arrogance and hubris as a species as being central to that; and because I see injustice in terms of what that inflicts upon other species — for all these reasons, I am impelled to work within that realm.

And so I find that many of my projects that are not necessarily connected at the outset, and even that do not start out with those questions in mind, ultimately end up addressing those questions in some way. So that I've been working now for a decade or more on a project trying to reimagine democracy. And that project has resulted in the recognition of more profound and radical and fundamental changes beyond just the changes that need, I believe, to take place, or at least the questions we need to be asking about how humans interact in terms of democratic decision making, to recognize that humans should not be the only ones making those decisions. In fact, we need to involve other species; we need to enfranchise other species.

Space.com: So, how does it feel to have a monograph written about you and your work? What is it like to be memorialized in this way, celebrated in this way?

Keats: The plurality of perspectives counteracts the potential for the monograph to be a consolidation, in the sense of being a resolution. And therefore, I think that what I gained from it has been a set of different mappings, or a set of different perspectives that actually seem like they might be generative. They might help me going forward, because none of them are definitive; no one is dominant. That might actually open up the space for further exploration.

Conceptually speaking, I think that I have managed to avoid what would have been the greatest peril. And I think that actually it can be a ramifying force or factor in my work going forward.

Space.com: When you say "the greatest peril," do you mean a sort of ossifying force? Of seeing the weight of the past two decades of your work and feeling a sense of satisfaction, or feeling a sense of being constrained by these boundaries that the book puts around you? Is that what you're trying to avoid?

Keats: I think that actually you've identified what would be the greatest peril, which is not what I was referring to. But I think that is absolutely right: Satisfaction would be catastrophic, because that would suggest that the only thing left for me was retirement.

I see success as a sort of failure, where that success is a form of closure. And I think that that is more broadly what I have been cautious about and concerned about, in the process of working on this project with Alla and Julie — the risk that it is in some way definitive or, more broadly, defining.

Space.com: You've said that you don't like following the traditional way that thought experiments are done, which is to lead people down a path to a hypothesis that the originator has chosen. You want it to be far more participatory — you want everybody who comes into the gallery, or who experiences the experiment in some other way, to take some of it with them, and to put their own mark on it. That's the whole point of getting ideas out into the world, right?

Keats: Absolutely it is meant to be participatory. The experiment is meant to be experimental, in the sense that I'm setting out the initial conditions, and I don't know what the results will be. In my case, I'm not doing so necessarily in a Petri dish. But I am doing so as a matter of setting up circumstances — taking the thought experiment in philosophy as a framework for doing so where I am putting a counterfactual or an alternate reality out in the world where people can encounter it, and we can work out the implications together.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.