Will Europe Finally Get Its Asteroid-Deflection Mission Off the Ground?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

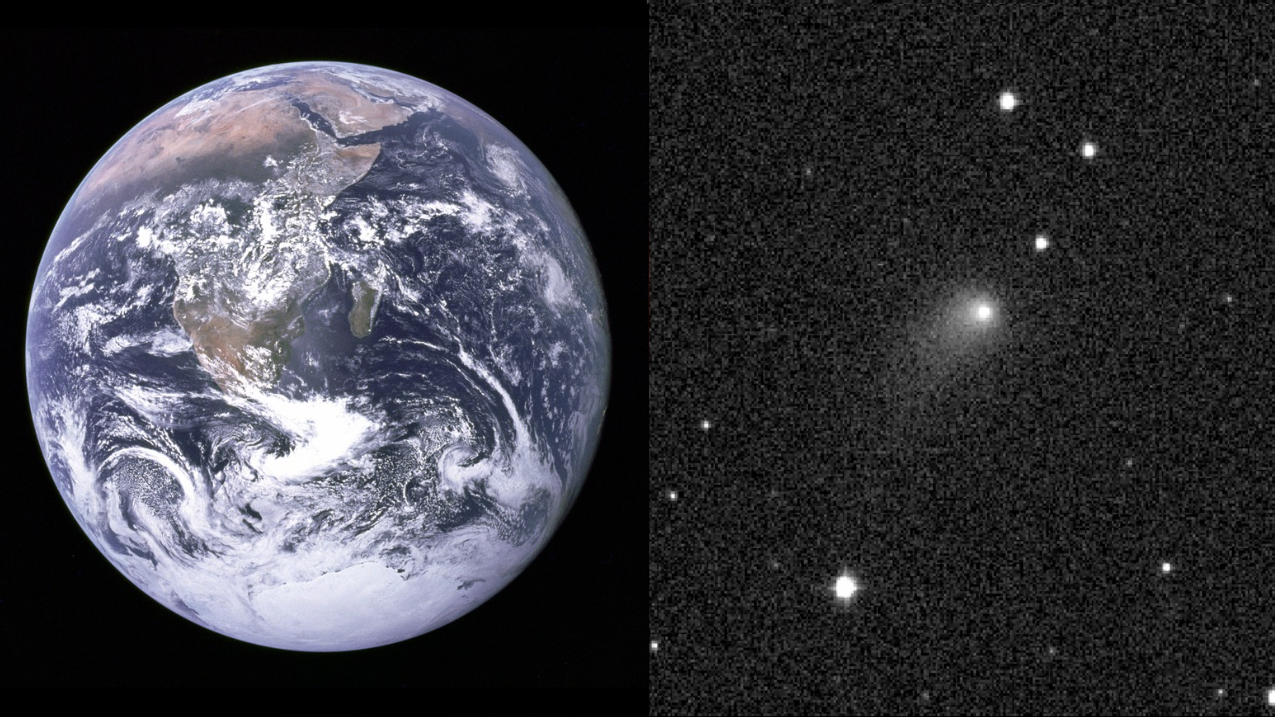

BERLIN — Scientists and public advocates are trying to rally support for a proposed European Space Agency (ESA) mission to the near-Earth asteroid Didymos.

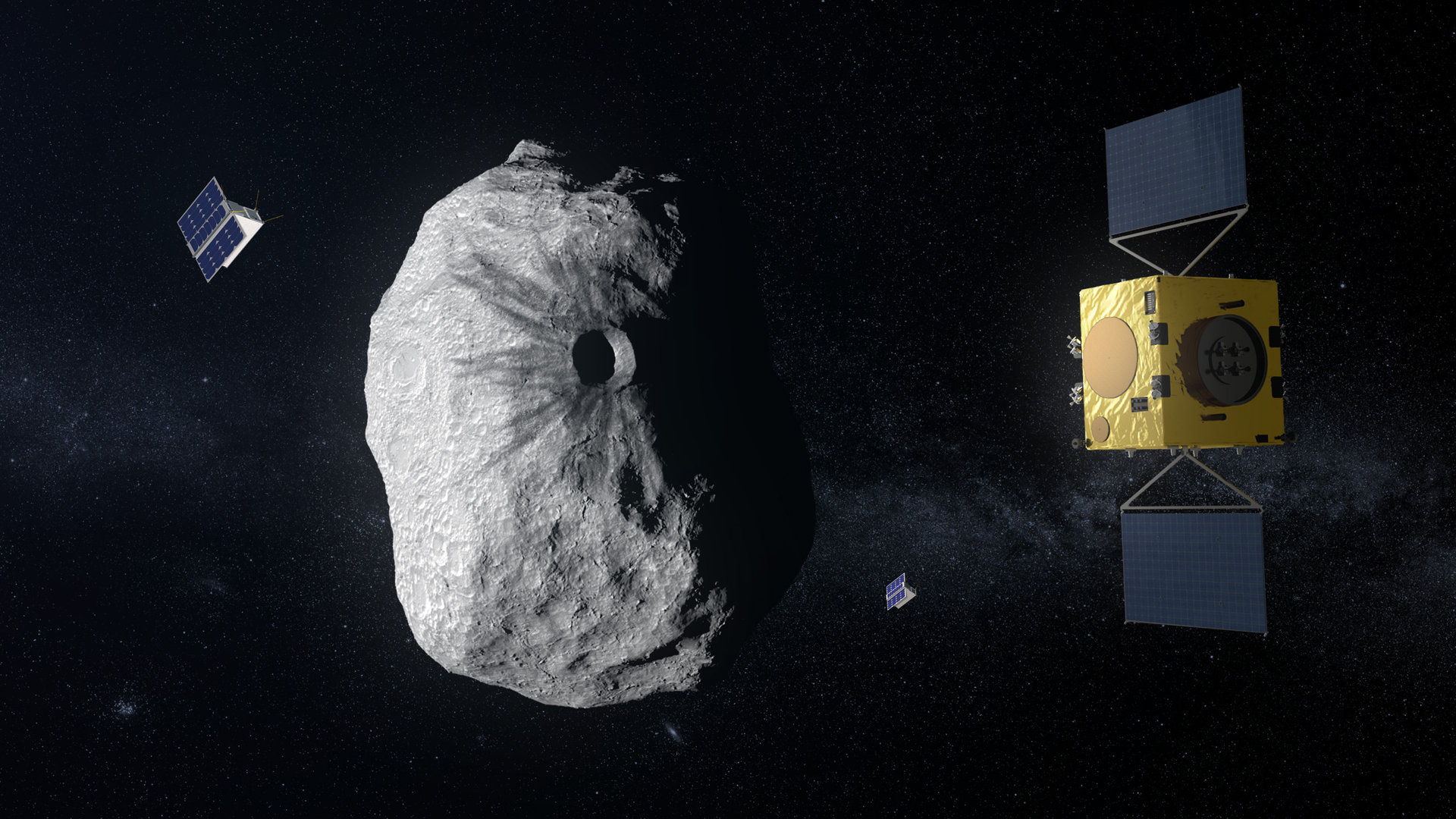

As a companion to NASA's Double Asteroid Redirect Test (DART) spacecraft, ESA's Hera mission would gather data that might be used in a planet-saving mission if we ever need to knock a space rock off a deadly collision course with Earth.

"To design a deflection mission, we have to predict what's going to happen," Kai Wünnemann, who leads the Berlin Natural History Museum's department of impact and meteorite research, send in a news conference held at the museum on Nov. 15.

Related: Humanity Will Slam a Probe into an Asteroid Soon to Help Save Us All

At the same event, Hera's supporters released a letter signed by more than 1,200 scientists and citizens calling on ESA members to fund Hera during their next ministerial meeting on Nov. 27 and 28.

During ESA's ministerial meetings, which take place about every three years, delegates decide on the budget for the years ahead. At the last meeting, in 2016, member states declined to fund an earlier version of Hera, named the Asteroid Impact Mission (AIM).

ESA's lead scientist for Hera, Patrick Michel, of France's Observatoire Côte d'Azur and the French space agency, is more hopeful this time around that the €290 million ($320 million) project will be approved.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The probability [of an asteroid impact] is low but the consequences are high," Michel told Space.com. "This is why it's relevant to take care of it. Moreover, we have the tools … We can't lose more time. We have studied this for 15 years, so what are we going to do if it doesn't happen this time? Do more paperwork? Spend more money?"

Didymos is a binary asteroid, meaning it's two space rocks. The bigger one is about 2,625 feet (800 meters) across and is orbited by a tiny moon, informally dubbed Didymoon, which is only 525 feet (160 meters) wide. (Didymoon's size is sometimes compared to the Great Pyramid of Giza.) If an asteroid the size of Didymoon were to collide with Earth, it would cause an explosion bigger than the largest nuclear weapon. But as far as targets in outer space go, Didymoon is considered quite tiny. No spacecraft has ever visited an asteroid this small.

NASA's DART probe will launch on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in June 2021, and in October 2022 it will crash into Didymoon at more than 3.7 miles (6 kilometers) per second, bumping the rock off its regular orbit around its companion. AIM was designed to witness the impact and study the effects. Hera, which was proposed last year, is a retooled version of that mission. If approved, it would launch in October 2024 and arrive at Didymoon in December 2026.

"You need a detective that goes to the crime scene to understand carefully what happened," Michel told Space.com.

Wünnemann explained that scientists have been running computer simulations and tests in the lab to predict what might happen during an asteroid deflection mission, but sometimes their predictions don't match up with reality. For example, models predicted that the impactor Japan's Hayabusa2 spacecraft launched at the asteroid Ryugu would create a crater only about 3 to 6 feet (1 to 2 meters) across but instead it carved a crater about 33 feet (10 m) wide. By measuring the crater DART creates and examining the properties and mass of Didymoon, scientists hope to be able to fine-tune their models.

Holger Sierks, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany who worked on ESA's Rosetta mission to a comet, said that we know of about 20,000 near-Earth objects today, "about 2,000 of which we really need to follow carefully so as to not join the collection of wonderful dinosaurs here in Berlin." Downstairs from the news conference, there were galleries with fossils of dinosaurs like T. rex that went extinct about 66 million years ago, after a 6-mile-wide (10 km) space rock catastrophically collided with Earth, wiping out 80% of life on the planet.

Even though an asteroid impact is probably the least likely natural disaster, it's worth preparing for because it might be the only natural catastrophe we can prevent, Michel said. "Even if we could predict an earthquake or tsunami, we wouldn't prevent it."

Earlier this year, ESA enlisted the help of Brian May, an astrophysicist and guitarist from the band Queen, to promote Hera in a video. "The scale of this experiment is huge," May said after describing the mission. "One day these results could be crucial for saving our planet. If an asteroid ever poses a real threat to Earth, we'll be ready."

- Doomsday: 9 Real Ways Earth Could End

- Black Marble Images: Earth at Night

- Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth

Follow Megan Gannon @meganigannon. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.