Water ice on the moon may be key for future space missions. But is there enough?

"Previous estimates for the expected amount of ice in cold traps have to be revised downward dramatically."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

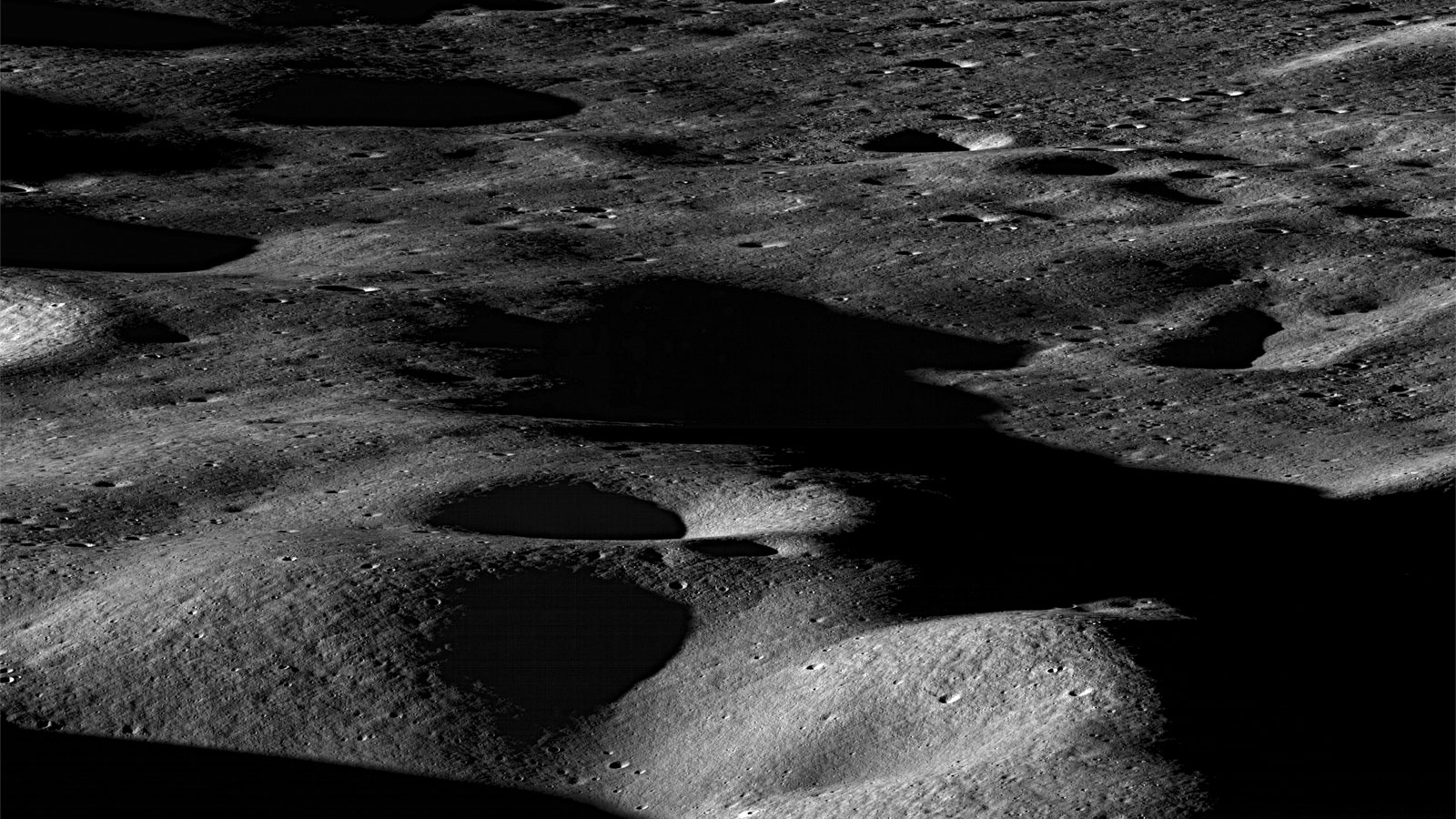

Frigid areas on the moon where the sun never shines are younger than the craters they reside in and, according to new research, likely host less water ice than previously thought.

These areas, known as permanently shadowed regions (PSRs), are pockets of lunar craters that several future moon landing missions are focused on. This is because PSRs are considered to be abundant reservoirs of water ice that can be harnessed by astronauts on the lunar surface to bolster life support systems and generate rocket fuel. The latter is especially intriguing because creating propellant right on the moon could help with return missions to Earth as well as deeper missions targeting Mars that'll use the lunar surface as a pitstop.

However, findings from the new study show PSRs are, at most, 3.4 billion years old. This means they are younger than the 4-billion-year-old craters that host them, hinting that our currently high estimates for water ice deposits on the moon need to be revised downward.

Article continues belowRelated: Incredible new moon images show Artemis 3 landing sites near the lunar south pole (photos)

"Impacts and outgassing are potential sources of water but peaked early in lunar history, when the present-day PSRs did not yet exist," Norbert Schörghofer, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona and the lead author of the new study, said in a statement.

To arrive at this conclusion, his team modeled the evolution of the moon starting from its formation 4.5 billion years ago — when a Mars-sized planet collided with Earth — continuing through its drift over time, and ending with its present-day position. The simulations showed that the moon experienced a major reorientation in the tilt of its spin axis roughly 4.1 billion years ago, when it reached 77° for a short period before subduing to lower values.

Although the moon may have had significant water ice at the time, "such high obliquities must have resulted in the loss of all ice deposits," researchers write in the new study.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the simulations, PSRs appeared near the moon's north and south poles and grew over time after the spin axis' reorientation, but the amount of frozen water hidden in these regions is likely to be less than previously estimated, researchers said in the same statement.

For future crewed missions, scientists are particularly interested in the southern polar region of the moon where they think plenty of volatiles — elements that zap from solid to gas when sunlight or solar radiation hits them — exist. For example, analysis of the debris blasting from the Cabeus crater after a NASA probe crashed in 2009 had revealed presence of usable water, which was found to make up as much as 8.5 percent of the lunar soil.

India's Chandrayaan-3 robotic lander-rover duo, which aced its touch down near the lunar south pole on Aug. 23, has also searched for traces of frozen water during its two-week mission, although findings from the collected data are yet to be announced.

This research is described in a paper published Sept. 13 in the journal Science.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.