February marks a month of 'combustible' planets and tricky skywatching

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

One astronomical term which is rarely used anymore is "combust," which refers to a celestial body that appears to be in such close proximity to the sun that it is impossible to observe.

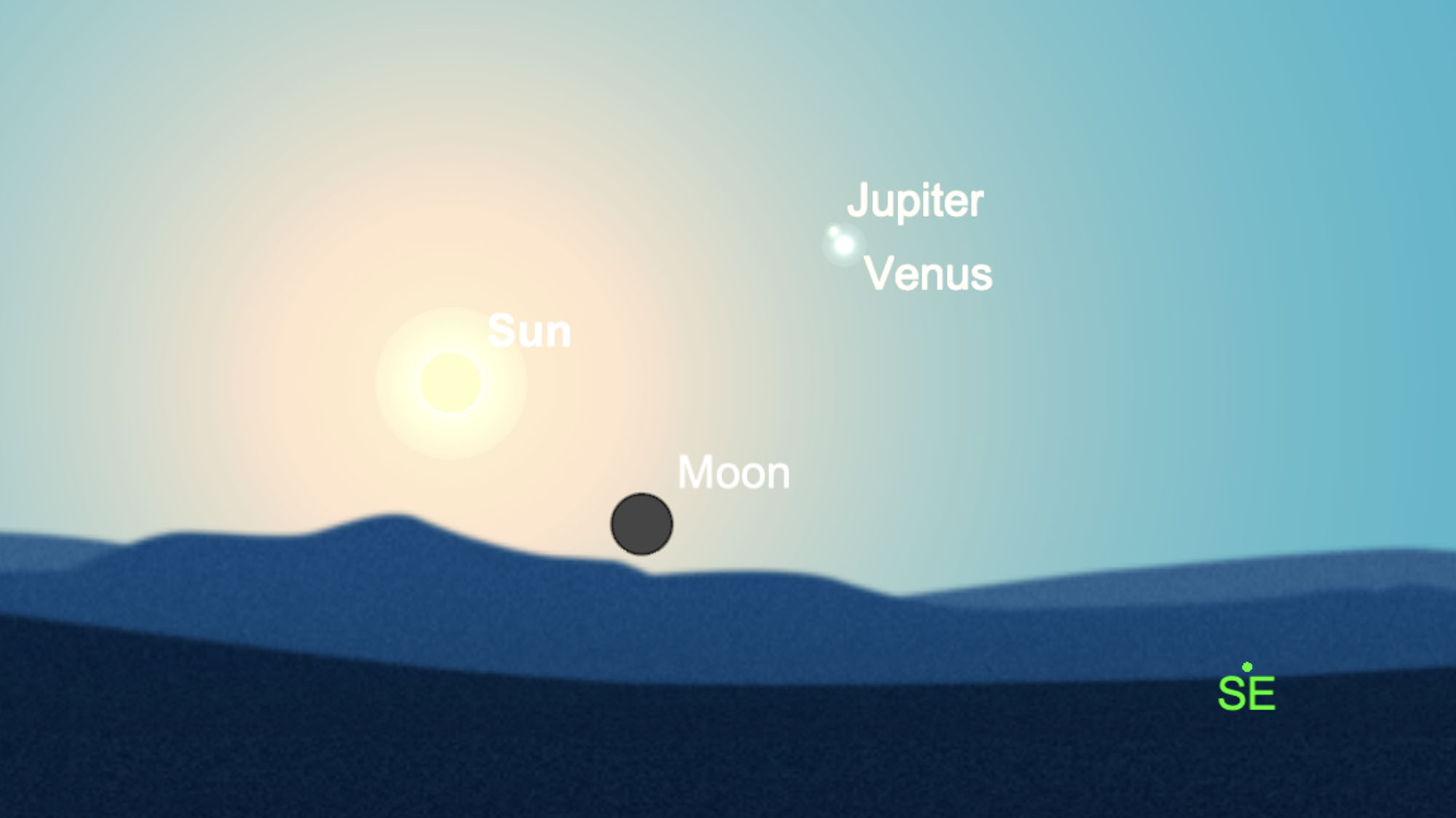

The moon is a very good example of this from roughly 18 to 24 hours before to roughly 18 to 24 hours after new moon phase. Of course, when the moon is new, we are facing that part of the moon that is not illuminated by reflected sunlight. But even when a narrow sliver of the moon's disk is illuminated, shortly before or after new, it may still be difficult, if not impossible, to see.

Similarly, when a planet is at or near solar conjunction, where it is on the opposite side of the sun from Earth, we could say that it is combust as well. And as it turns out, four of the five naked-eye planets could be considered combust at some point in February.

Related: The brightest planets in February's night sky: How to see them (and when)

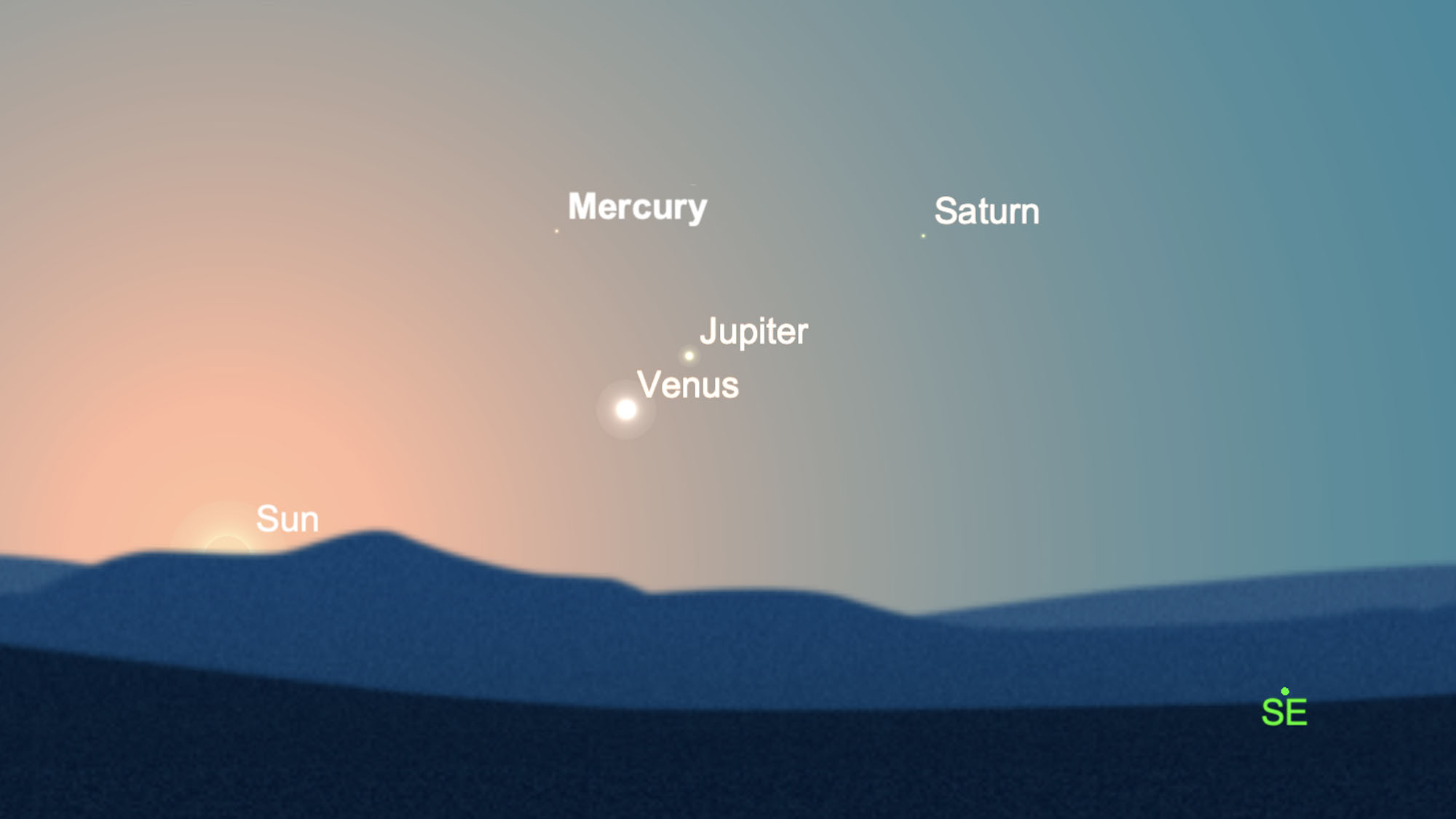

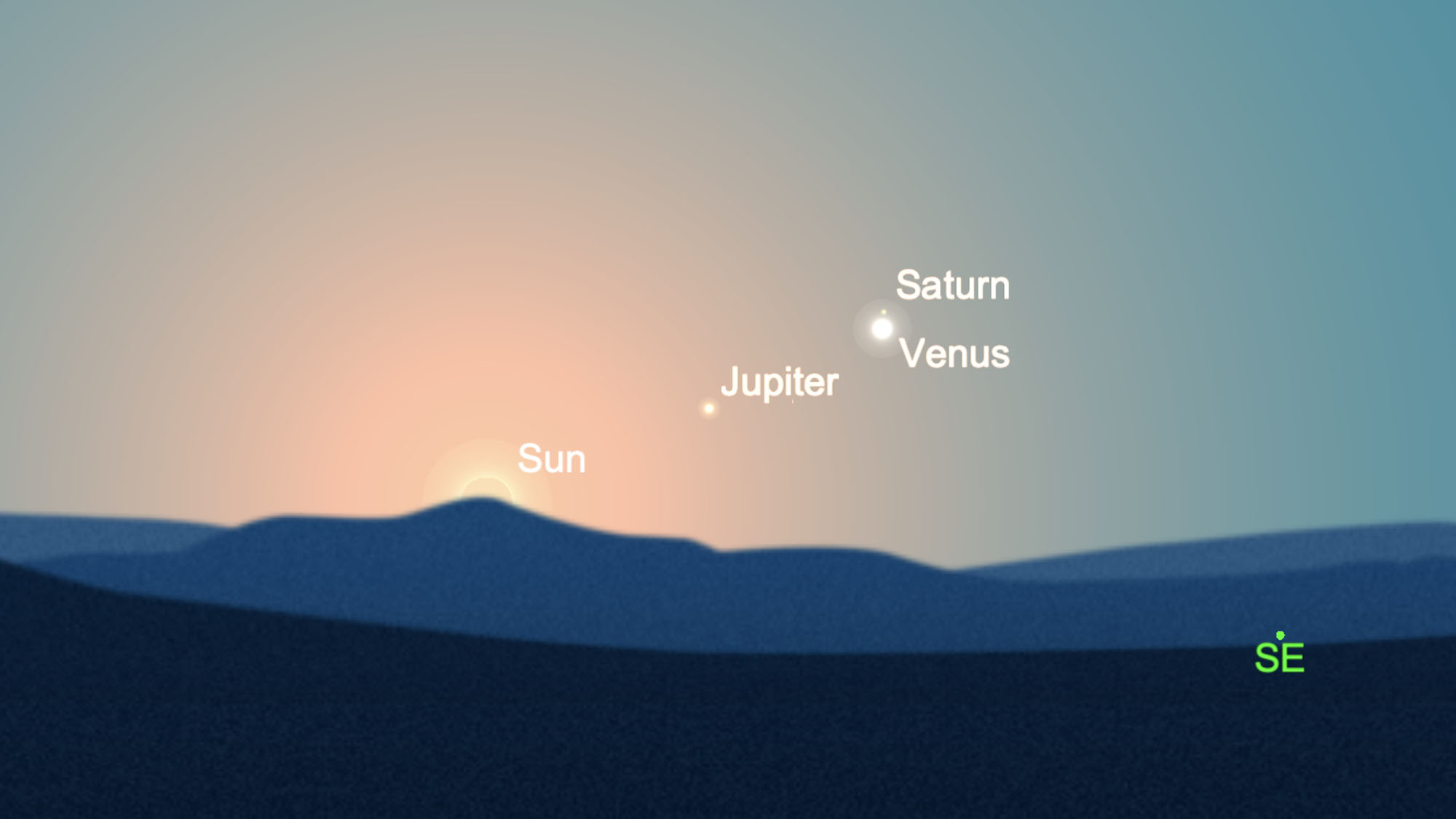

During February from our Earthly perspective, Venus, Jupiter and Saturn are on the far side of the sun, while Mercury is positioned between us and the sun. Jupiter may begin to emerge into view later in the month, followed by Saturn and Mercury, but their low altitudes in the bright light of dawn will make any prospective sightings rather dubious.

Normally, a seeming paradox would be on display. Although all the planets orbit the sun in the same direction, Venus can appear to travel in the opposite direction as Jupiter and Saturn. While all three planets are on the far side of the sun, Jupiter and Saturn move toward the celestial west (to the right) relative to the sun as they slowly emerge back into view in the morning sky. But Venus is leaving the morning sky, moving toward the celestial east (or to the left) relative to the sun.

Watching Venus — which is closer to the sun than Earth — is similar to a spectator watching a car speeding around a race track. When the car (or Venus) is nearest to us, it passes in front of us moving from left to right. It then curves away, and as it speeds around to the far side of the track, it appears to move from right to left.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But Jupiter and Saturn move in orbits far beyond the Earth and Earth moves considerably faster than either planet, so their apparent positions in the sky relative to the sun are controlled by our orbital motion. So, when these two planets are positioned on the far side of the sun, they appear to move in the opposite direction to Venus: left to right.

Like ships passing each other, Venus will have a very close conjunction with Saturn on Feb. 6 and with Jupiter on Feb. 11. Mercury will join Venus and Jupiter on Feb. 13, with the three planets crowding into a tight circle less than 5 degrees wide. Normally, these would all be eye-catching spectacles, but because they'll occur very close to the sun, these are sights that will go unseen.

After all, all four planets are combust!

Mars: odd planet in and out!

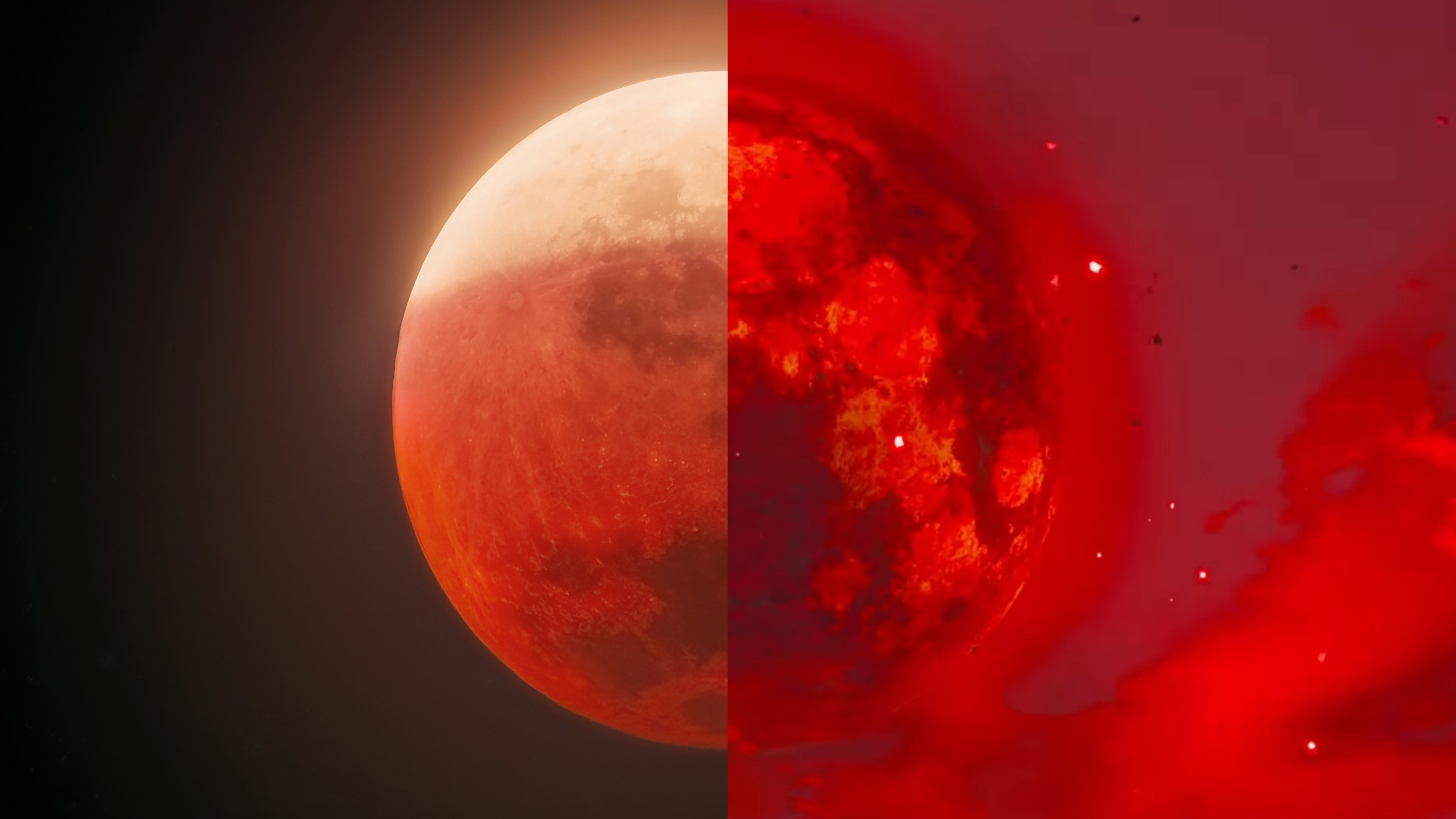

The only naked-eye planet that is visible, and quite readily we might add, is Mars. Back in October, Mars was spectacularly bright because it was passing unusually close to the Earth. Now, it is about 77 million miles (125 million kilometers) more distant, and about 17 times fainter in the sky.

But Mars remains well-placed for viewers, visible high in the south-southwest as darkness falls at a respectably bright magnitude of 0.5 — about as bright as Vega, the fifth-brightest star in the night sky — and not setting until after 12:30 a.m. local time. (Magnitude is a measure of brightness, with negative numbers denoting the brightest astronomical objects.)

Of course, because all the planets are constantly shifting in their respective orbits, our viewing perspective for all of them is constantly changing.

Later this year, the current situation will be reversed. During the last week of October 2021, we will have the mirror image of the current sky, with four out of five planets in fine position to be seen. At sunset, brilliant Venus will be visible in the west-southwest, remaining in view for up to two and a half hours after sunset. Meanwhile Saturn and Jupiter will — like last summer — call attention to themselves at nightfall in the south-southwest. And early risers can catch a view of the usually elusive Mercury, visible low in the east about an hour before sunrise.

And what of Mars? It will be the sole planet "out of the loop," hidden in the glare of the sun. It's an example of a planet experiencing a long "combustible period." We might even say that Mars will be on a four-month sabbatical of sorts, disappearing into the sunset fires late in July and not reappearing into view until late November, when it will be rising just before the sun.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.