Aliens watching us? Scientists spot 1,000 nearby stars where E.T. could detect life on Earth

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

As humanity ramps up its search for alien life, we should keep in mind that E.T. might be hunting for us as well.

A new study makes that point by identifying more than 1,000 nearby stars that are favorably positioned for spotting life on Earth.

"If observers were out there searching [from planets orbiting these stars], they would be able to see signs of a biosphere in the atmosphere of our Pale Blue Dot,” study lead author Lisa Kaltenegger, an associate professor of astronomy at Cornell and director of the university's Carl Sagan Institute, said in a statement.

"And we can even see some of the brightest of these stars in our night sky without binoculars or telescopes," Kaltenegger said.

Related: 10 exoplanets that could host alien life

Earthly transits?

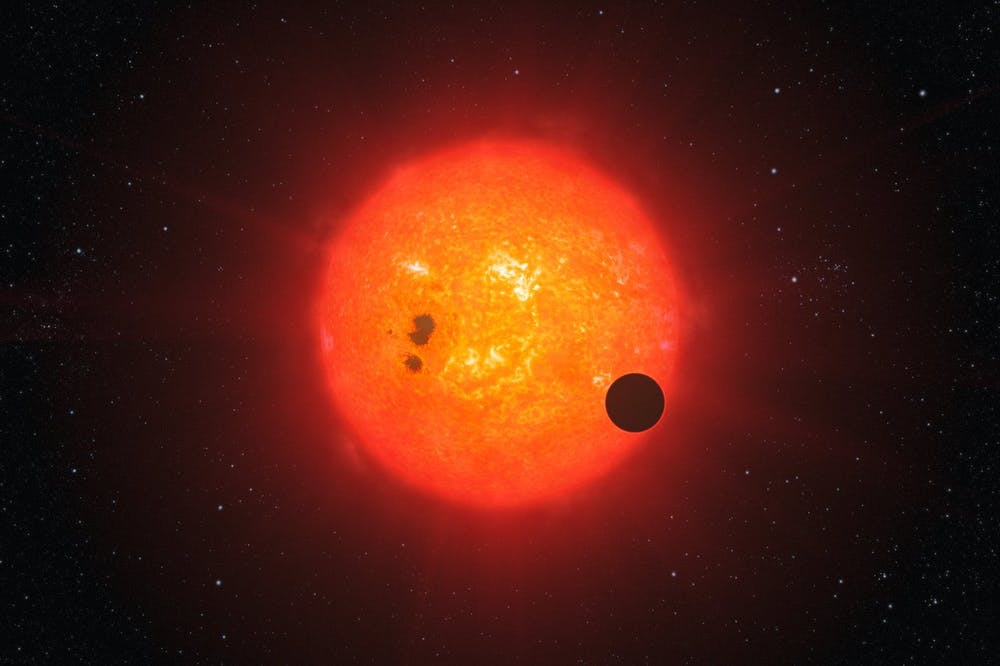

Astronomers have found most of the more than 4,000 exoplanets discovered to date with the "transit method," which detects the tiny brightness dips caused when an orbiting world crosses its host star's face from the observer's perspective. This strategy was used to great effect by NASA's pioneering Kepler space telescope and is currently being employed by its successor, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS).

Soon, researchers will also be able to scan the atmospheres of some nearby transiting planets for potential signs of life. This search will be one of the many tasks undertaken by NASA's $9.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch late next year, for example. And coming ground-based megascopes such as the Giant Magellan Telescope will do such work as well.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the new study, Kaltenegger and co-author Joshua Pepper, an associate professor of physics at Lehigh University, thought about Earth as the target of a transiting-planet survey rather than the source of one.

The scientists scrutinized the datasets of TESS and Europe's star-mapping Gaia spacecraft, looking for stars within 100 parsecs (about 326 light-years) that are aligned with the ecliptic, the plane of Earth's orbit around the sun. (Such alignment is necessary to see Earth cross the sun's face.)

This search turned up 1,004 qualifying main-sequence stars — stars that, like our sun, fuse hydrogen into helium in their cores. And 508 of those stars "guarantee a minimum 10-hour-long observation of Earth's transit" across the sun's face, Kaltenegger and Pepper wrote in the new study, which was published online Tuesday (Oct. 20) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters.

A new tool for the E.T. search

The new results deal only with stars. Scientists don't know how many planets orbit the 1,004 suns flagged by Kaltenegger and Pepper, let alone how many of these systems host worlds that may be conducive to life as we know it.

Those numbers should come into clearer focus as exoplanet hunters like TESS continue their work. And the new study can serve as a signpost for astrobiologists in the meantime and into the future, Kaltenegger said.

"If we’re looking for intelligent life in the universe that could find us and might want to get in touch, we've just created the star map of where we should look first," she said.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.