European space partnerships with Russia face uncertain future amid Ukraine tension

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronauts regularly tout how living aboard the International Space Station tears down barriers. Right now, two Russian cosmonauts and one European astronaut are living in orbit together with four Americans. The seven spaceflyers are enjoying the fruit of international cooperation that dates back to the historic 1975 Cold-War era docking between the U.S. Apollo and Russian Soyuz spacecraft.

But back on Earth, fears over a major conflict in Europe are rising as more and more Russian troops assemble on Ukraine's border, threatening a full-scale invasion of a sovereign country. The United Nations' Secretary General António Guterres described the developments as "the most serious global peace and security crisis in recent years."

Related: US launch providers eyeing Russia-Ukraine situation

But what does the geopolitical situation mean for the hailed cooperation in space, and especially where Europe collaborates with Russia? Through the European Space Agency (ESA), 22 European countries (Ukraine is not one of them) partner on space research and exploration. Russia's space agency, Roscosmos, has been an important partner for years, taking part in some of Europe's most high-profile space exploration endeavors.

Untying these bonds would certainly be complicated. But as European countries roll out sanctions against Russia, many of which will affect not only the citizens of Russia but also Europeans, can ESA and Roscosmos continue business as usual?

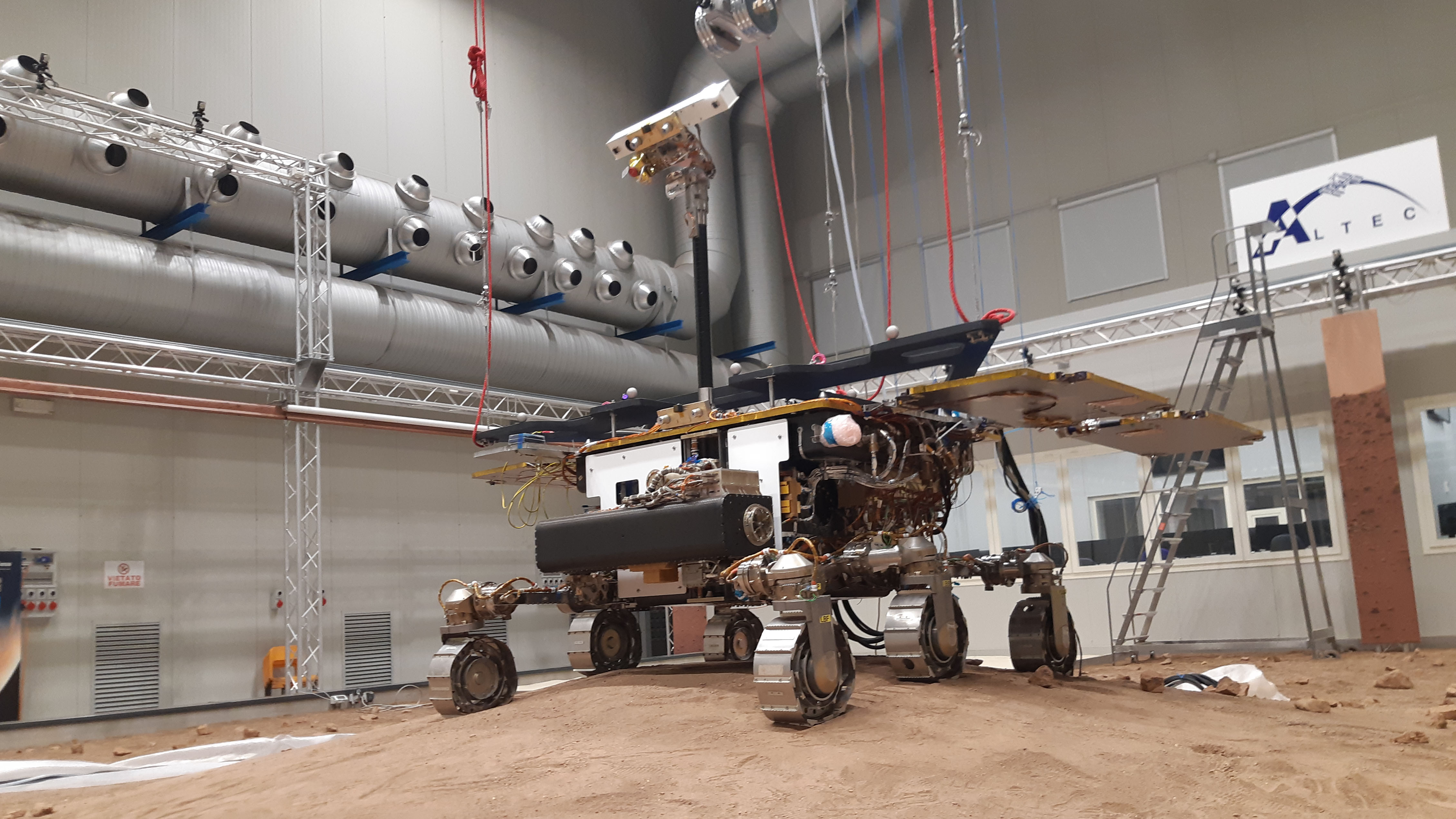

For ESA, the biggest pain point might be the ExoMars mission's Rosalind Franklin rover, the first European rover designed to land on Mars. The mission, initially expected to launch in 2018 and delayed because of ongoing problems with its landing parachutes, is finally scheduled to lift off from Russia's Baikonur Cosmodrome in September.

It's been a long and painful journey for ExoMars to get up to this point. Originally a cooperation between ESA and NASA, the mission was nearly canceled in 2012 after budget cuts by President Barack Obama's administration forced the U.S. space agency to withdraw. The mission, built to search for traces of life underneath Mars' surface using a six-foot (2 meters) drill, was only resuscitated after Roscosmos stepped in to fill NASA's shoes.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In addition to launching ExoMars on its Proton rocket, Russia has also built the Kazachok landing platform and provided several scientific instruments for the rover as well as the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), which forms the first part of the ExoMars mission. TGO reached Mars in 2016 with the experimental Schiaparelli lander that crashed due to a software glitch.

The European Space Agency (ESA) declined to comment on any implications the Russia-Ukraine situation might pose to ExoMars or other joint projects.

But researchers at dozens of institutions across Europe have spent years working to put their tech on the surface of the Red Planet. Moreover, because of its drill, the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin rover is more likely to find traces of any life Mars may once have had than its American counterpart Perseverance, astrobiologists believe.

"We have a great cooperation with our Russian scientific and engineering colleagues, including some joint calibration tests going on in Turin [Italy] this week," Andrew Coates, a professor of physics and planetary scientist at University College London, told Space.com in an email.

Coates is the principal investigator on the PanCam instrument, the scientific eyes of the ExoMars rover, and previously helped to build Perseverance's primary scientific camera Mastcam-Z, but also one for an earlier failed European attempt to land on Mars, the 2003 Beagle 2 mission.

So far, he said, he expects the ExoMars rover to launch as planned during a twelve-day window between Sept. 20 and Oct. 1.

"Science transcends politics, and we are sure all is well for the launch," Coates said.

ESA may have other tough decisions to face as well. European spaceflight provider Arianespace uses Russia's Soyuz rockets alongside the smaller Vega and the larger Ariane 5 vehicles to launch payload from the European Spaceport in Kourou in French Guiana. The cooperation, ESA says on its website, improves Russia's access to the commercial launch market.

ESA planned to partner with Russia on the development of future launchers, according to the same website, as well as on a series of satellites studying the effects of space on living organisms.

Whatever the European space community decides, the space industry's claims about contribution to international peace risk to sound rather hollow in the future. The International Space Station, arguably the grandest engineering endeavor in humankind's history and a hallmark of post Cold-War cooperation, was, ironically, proposed for a Nobel Peace Prize nomination in 2014, the very same year that Russia annexed the formerly Ukrainian territory of Crimea. The war that has been raging in the region ever since has to date claimed more than 14,000 lives.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.